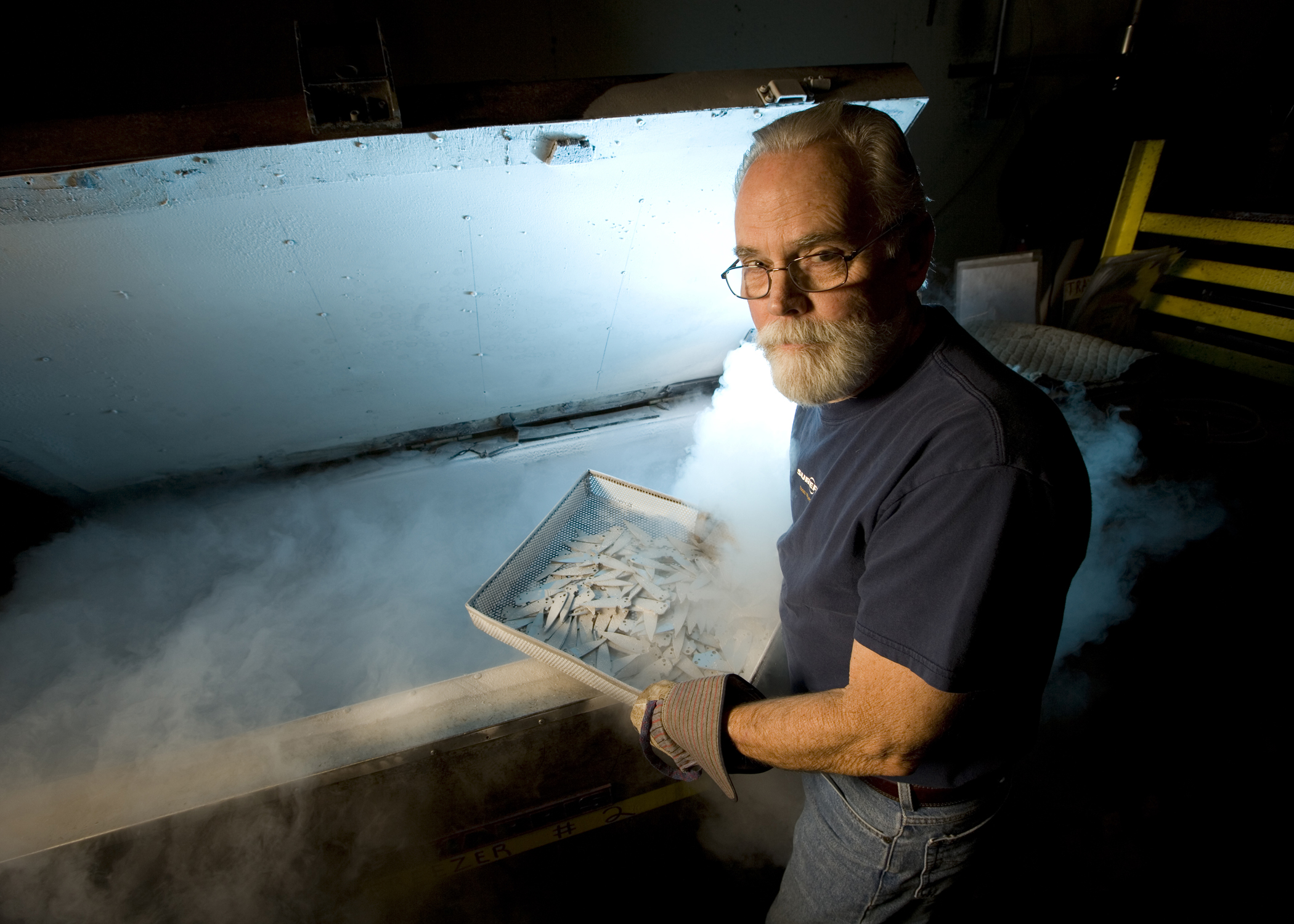

Cryogenic quenching may be performed on a single blade or hundreds at a time. Blade Magazine Cutlery Hall-Of-Fame© member Paul Bos said he may do a single blade or put a large quantity in a basket for immersion at one time, and control the rate of cooling and return to room temperature precisely. (Buck Knives photo)

Given the right steels, cryo treatments can enhance overall performance as well as aesthetics

By Mike Haskew, BLADE® field editor

Whether called cryogenic quenching or the probably more correct cryogenic treating of the steel, the process of freeze treating to help make a steel the best performer it can be is nothing new. Since the U.S. military became involved in cryogenically quenching steels during World War II and required it in the manufacture of various defense-related products, several methods have been evaluated with the same goal in mind: optimizing the amount of martensitic iron in the structure of the steel while minimizing the residual amount of austenitic iron. In turn, the qualities most sought in a knife blade are enhanced, particularly edge holding.

“There are different ways that cryogenic treating is performed,” explained Scott Devanna, vice president of marketing and product development for Carpenter Steel, “but all methods are designed to accomplish the same goal, although the methods sometimes attain differing degrees of transformation from austenite to martensite. Cryogenic treatment is not a different type of quenching method but is an additional treatment normally used after quenching. It’s used after the quench in an effort to achieve more complete transformation of austenite to martensite [martensite being the hardest of the transformation products of austenite].

“Most tool steels actually develop their hardened structure, or martensite, during the quench,” he continued. “For various reasons, however, in some cases transformation to martensite may not be complete even at room temperature. In such cases, some of the high-temperature microstructure, or austenite, may be retained after normal heat treating.”

A2 and D2, as well as other high-alloyed tool and specialty steels, may contain as much as 20 percent austenite after normal heat treating. Cooling the steel to cryogenic temperatures furthers the conversion to martensite. However, the process is specialized and requires close attention to actual temperature, levels of exposure, and the time intervals involved in raising and lowering the temperatures of the steel itself.

“The newly formed martensite is similar to the original as-quenched structure and must be tempered,” Devanna warned. “Cryogenic treatments should always be followed by tempering. Often the cryogenic treatment is actually performed between normally scheduled multiple tempers. Technically, cryogenic treatments are most effective as an integral part of the original quench, but due to the high risk of cracking, it’s recommended that tempering or a snap temper be performed before any cryogenic treatments.”

The cryogenic quench itself is performed primarily in two ways: shallow and deep treatments. In the shallow treatment, the blade steel is brought to approximately -112°F for five hours, while in the deep treatment it is reduced to roughly -321°F for about 35 hours. This is most often accomplished through immersion in liquid nitrogen.

“The term quench tends to imply that there’s a rapid change in temperature,” noted Spencer Frazer of SOG Specialty Knives & Tools. “In the case of cryogenic treatment, the quench term is quite misleading. Due to the severity of the temperature involved, quenching the material would cause it to crack or fracture. For that reason, cryogenic treatment is performed using computer-controlled temperature changes. At SOG, we use a version of deep cryogenic treatment, and some adjustments were made to the standard method to best suit the knife steels SOG uses. We consider it a supplementary process that helps improve the wear resistance of the blade steel.”

Blending In The Clumps

Blade Magazine Cutlery Hall-Of-Fame© member Paul Bos began heat treating knife blades in the 1950s. Back then he worked in the aircraft industry and treated a number of components. He said he also has seen the cryogenic process produce higher performance in guitar strings, women’s nylon stockings, gun barrels and engine parts.

“I figured if the military wanted it done, then it would be good for knives,” Bos said. “Originally, it was there to get rid of austenite in martensitic steel. Austenite makes steel brittle, and under a microscope you can see what looks like little clumps of carbon. The cryogenic process is like putting stuff in a blender with clumps and pretty soon everything is mixed in a fine solution. Once you do the cryo on a steel, then the austenite dissipates and you are left with a fine grain structure.”

Bos does a snap temper on high-carbon tool steel and then the cryogenic process at -280°F for about eight hours, and then brings the steel slowly back up to room temperature before a second temper. While cryogenic quenching is not a necessity on high-carbon steels*, its effects are more profound on higher-alloy-content steels, which do not completely transition from austenite to martensite at room temperature.

“Once the steel gets past -100°F it’s in a state where you aren’t hurting it, but you can’t leave it in there too long,” Bos added. “Some guys go right from the quench into the cryo, but the blade could crack or break, and I don’t do that because I can’t take a chance with my customers’ blades.”

Both factory and custom knifemakers take advantage of cryogenic quenching, and the process may be performed on a single blade or hundreds at a time. Bos’s career has spanned decades of heat treating blades for Buck and for a vast number of custom makers, including some of the most famous of all time. He may do a single blade or put a large quantity in a basket for immersion at one time, and control the rate of cooling and return to room temperature precisely.

According to Bos, creating the optimal transformation of austenite to martensite is an integral part of the heat-treating process. To obtain the maximum formation of martensite, two or more complete tempering cycles are necessary following the sub-zero cryogenic quench. He stressed that the blades always should be allowed to cool to room temperature between tempering sessions.

Deep-Treatment Believer

For many custom makers, the benefits of cryogenic quenching are proven in the knife’s overall performance. Bob Beaty is a firm believer in the deep treatment below -300°F. A knifemaker since 1994, he does, however, note that simple steels do not seem to exhibit enhanced performance as a result of the procedure.

“I do both forging and stock removal,” Beaty remarked, “and basically you find most of the benefit in the more complex stainless steels. I believe the knife stays sharper longer, and I’ve tested that a lot and am still testing it. Once a month I’ll cut rope, cardboard and leather. I always get a big difference, probably a 40-to-50-percent difference in edge-holding capability, as the cryogenic quench refines the grain of the steel.”

Though he admits there are skeptics, Beaty says the enhancements of the cryogenic quench are real. In fact, he says he has experienced fewer incidences of edge chipping and an easier time getting a mirror finish on a blade after the cryogenic treatment.

For the custom maker, outsourcing cryogenic treating remains the most efficient method of getting the job done. “I recommend it for those makers using complex steels, and I’m only charged a small amount for the blades I send for cryo treating,” Beaty noted. “One of the downsides of liquid nitrogen is it evaporates, and that would make the process more expensive for me. Not only would I have to buy the nitrogen, but also the tank and other equipment, including an oven. It really does not add much to the overall cost of the knife. Of course, if you wanted to, you could cryo treat something in a thermos bottle. Just don’t put the lid on it, don’t put your hand in it, and don’t do it in your wife’s kitchen!”

A Difference Maker

The choice of steel apparently drives the benefit of the cryogenic quench. From a knife buyer’s standpoint, a cryogenically treated blade could make the difference in performance and easily justify any minimal added expense.

*According to Paul Bos, high-carbon steel usually is any steel containing anywhere from .6 to 2 percent carbon.

For more on the latest knives, knife legislation, knifemaking instruction, knife trends, knifemakers, what knives to buy and where and much more, subscribe to BLADE Magazine, the World’s No. 1 Knife Publication. For subscription information click on http://www.shopblade.com/product/blade-magazine-one-year-subscripti…?r+ssfb040312#BL1SU.

BLADE’s annual Knife Guide Issue features the newest knives and sharpeners, plus knife and axe reviews, knife sheaths, kit knives and a Knife Industry Directory.Get your FREE digital PDF instant download of the annual Knife Guide. No, really! We will email it to you right now when you subscribe to the BLADE email newsletter.

Click Here to Subscribe and get your free digital 2022 Knife Guide!