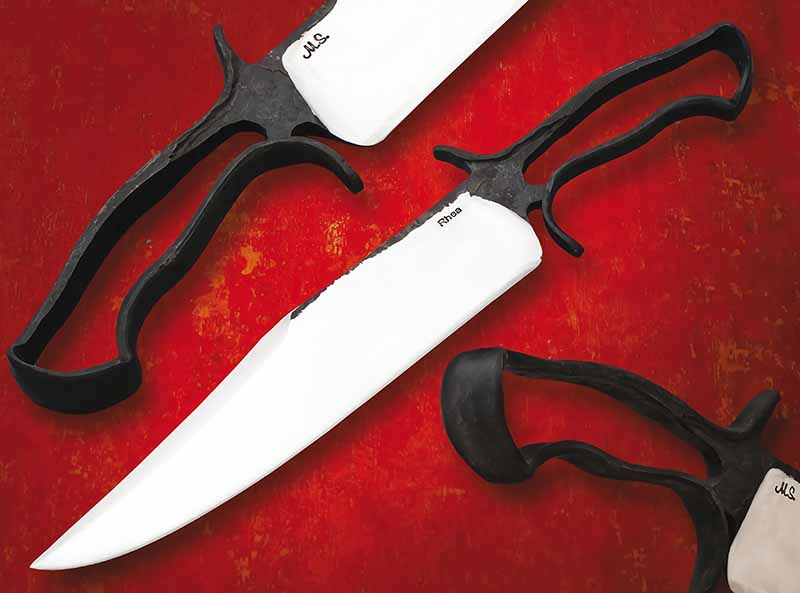

The X-Rhea Is The Result Of Having A Curious Mind And The Ability To Explore Possibilities.

Why did I come up with the X-Rhea knife design? I’ve asked myself this several times and only recently have I been able to supply a reasonable answer. Th e X-Rhea started as a personal challenge. I wanted to make a knife, handle and all, from one piece of steel. Th at’s it: no scales, no added glues, pins, extra space fillers, inlays—nothing. Moreover, I wanted it to look good and be comfortable and as structurally sound as any good knife should be, without being overly heavy.

This challenge nagged at me. If I limited myself to steel and fire as my basic resources, could I forge a knife from one piece of steel, a knife that left no doubt about its viability? Could it look good, feel good and perform well? I also wanted a handle design versatile enough to fit different sizes and types of knives.

“A full tang knife is stronger than a hidden tang knife” is something I’ve heard many times. That statement oversimplifies the matter; which is better? I’ve heard some say, “At least with a full tang, if the scales fall off you still have a knife.” While I don’t agree with either statement, it indicates in some people’s minds a full tang blade alone qualifies as “a knife,” even without scales. And what qualifies as a knife, as well as what part strength plays, might differ from person to person.

In my visits with renowned historic blacksmith Peter Ross, my eyes were opened to the multi-dimensional vision the historic blacksmith needed in order to execute the complex forgings of everyday objects of the colonial era. The ability to understand how something is shaped, combined with the hand skills to actually shape it, are two separate things. The combination of those two qualities in one individual is rare. Peter showed me how to change the way I think about shaping steel. My mind raced with possibilities every time I worked with him. He taught me how to take a project from concept to reality.

Just as steel is shaped by the blows of a hammer, my thoughts were shaped to the challenge at hand. I felt I was in a unique set of circumstances that directed me to mix my forging with the mostly forgot ten techniques of historic blacksmithing. My years of training helped provide some ability to execute my ideas and theories. Theories? OK, it’s my “theory” that about 90 percent of tactile, meaningful contact between the hand and a knife handle is concentrated on the top and the bottom. Think pliers, wrenches, etc. The mind seems to understand the vacancy of the remaining areas between the top and bottom. Also, the hand “soaks up” and “fills in” to meet these vacancies to a degree. If I could add contouring and sculpting to the essential top and bottom, could the hand and mind fill in the rest? Can a knife with no scales be an option?

The Answer To X-Rhea

Finding the answer took significant effort and a lot of time. I worked out a forging sequence for my X-Rhea hunting knives that satisfied me, but I kept thinking it would be great to forge a bowie with top and bottom lugs. It took years to work out the stages of the process. While the accompanying photographs attest to my relative success, it leaves a lot unsaid about the adjustments I had to make in my thinking. I used the blacksmithing principle of eliminating things that hinder the process, and re-emphasizing and adjusting things that assist it. I also considered efficiency in timing, appropriate temperature, or other techniques** that are most practical.

While modern tooling could speed up some of the steps in my process, modern thinking and modern expectations would not. Aft er all, this process was being developed around the early 19th-century blacksmith tools: a coal forge, blacksmith leg vise, and the use of handheld hammers. This uncluttered my thinking and required me to face the same challenges as the early blacksmith. Elevating one’s skills with basic tools, improving understanding of the materials, and bearing full responsibility for the outcome was my expectation. While this might seem restrictive and limiting, the improved skill level and the readjusting of my views had a freeing effect. I am not as dependent on modern tools, which enables me to be more creative. The willingness to adjust one’s thinking was, and remains, an invaluable aid to the blacksmith.

Material Limits

When forging a complex shape, a smith must consider the limitations of the material, sometimes working near its limits but never exceeding them. Wisdom calls for choosing material suited for the extreme changes of geometry in the knife. Steels that are prone to air hardening must have special consideration or be avoided. Like some historic objects, the X-Rhea Knife is forged from one piece of steel, in this case, entirely high carbon steel. Those qualities and characteristics must be allowed for and considered.

Making an X-Rhea is a multi-step process. It must be pre-formed, with all needed parts and adjustments made before final shaping and peening the handle. Recognizing and maintaining a high standard of precision in the pre-form details is absolutely necessary to a satisfactory final result.

Even after I successfully made one of these knives, I found that part of the challenge was yet to come—acceptance. I showed up at a cutting competition with one of my X-Rhea bowies and sure got some stares. The safety judges looked it over as if it were a new species of animal. “Is it strong? Will it hurt your hand?” they asked. As I recall I placed well in the competition using it, but the initial reaction was still mixed.

Will it hurt your hand? I previously mentioned the handle contouring and sculpting. This is a standard part of the forging and filing process, as it is with any knife handle. Depending on the maker’s forging skill, it may require some filing in-between forging steps. Each step has some amount of adjustability to allow for correction, while leading to a beautiful profile and comfortable grip. It can be surprising to those who handle the knife just how good it feels, considering the remarkable difference in construction and the “open” appearance.

X-Rhea Strength

Is it strong? This is where the application of common blacksmith tool-making skills and logic are applied. Sufficiency was the guide for an early blacksmith. Making a piece overly strong for its intended use might sound impressive, but in use it becomes clear that this strength adds unneeded and undesirable weight for the intended use, and does not account for other desirable characteristics such as flex and toughness. I view heavy,

unwieldy blades generally as a mark of a novice. Unless the intended purpose calls for excessive strength, sufficiency should also, be the guide not only for blades but for knives overall.

Today when I see a thickly built knife, instead of looking at it and saying to myself “This thing sure is strong!” I ask, “Why does it need to be so heavy?” For the X-Rhea handle, I try to use sufficiency as my guide. Where it can structurally be lightened, I do that by forging and filing, leaving it sufficiently strong but not overly heavy. This distribution of strength serves to provide literal balance to the knife exactly as any conventional knife, regardless of construction. Either should have balance when properly built to a purpose and have sufficient strength to perform its purpose. That fact, while amazing to me at first, is testimony to the principle of sufficiency. In other words, the X-Rhea should compare well in balance and weight as well as function to any well-made conventional knife for the same application.

For those inclined to overthink a matter, look at the “T” cross-section of the blade-to-handle transition. It effectively converts the stress loads in the needed directions. Viewed from the profile, the slight rotation of the ricasso as an “X” instead of a vertical “cross” assists in adding strength with less material (weight) to the connection. The upper leg of the ricasso’s “X” tapers back to brace the upper part of the handle, which bears the majority of the workload. The handle then tapers in thickness slightly as it goes back to the forged integral pommel and proceeds to the handle tenon where it is peened. To further lighten the knife, the handle band is sculpted gently to taste. Taste? I try not to get so engrossed in the math and mechanics that I lose the necessity of making the knife look good. Like a scroll forged by a blacksmith, the application of math and mechanics are the basis for all aspects of proportion and form. To keep it simple, I want to make it graceful, not blocky, getting the absolute most out of a minimum of material volume.

The X-Rhea Process

In my situation, I set a challenge for myself and it led to the X-Rhea. For me, the process is as important as the knife itself. I made a lot of individual knives, some better than others, but what I was actually concentrating on was developing a forging process, so the one-piece forged knives could be repeated via a repeatable process with predetermined features, checkpoints and adjustability built-in along the way. To emphasize adjustability, whether by forging, grinding or filing, is key. It enables the smith to reach predetermined checkpoints before proceeding with the rest of the process. When following a well-designed process, the outcome will be consistent and meet a standard as would the product of a well-designed and adjusted machine.

While we are far from machines that guarantee specific outcomes, diligent attention to the execution of each heated and hammered step and making needed adjustments, when appropriate, will carry the project along. As aptly pointed out in David Pye’s book, The Nature and Art of Workmanship, “The quality of the result is continually at risk during the process.” Overcoming the risk by careful determination, as well as time spent in practice, is its own challenge and entirely rests upon the craftsperson.

I believe it is noble to preserve cultural objects, and it’s also my belief that preserving the processes used to make those objects is equally important. The hand of the individual craftspeople, following already established processes, can be seen in the objects of the past. A society or culture can lose appreciation for the craftsman’s touch. Pye stated, “The danger is not that the workmanship of risk will die out altogether but rather that, from want of theory, and thence lack of standards, its possibilities will be neglected and inferior forms of it will be taken for granted and accepted.” It would be a shame to neglect the possibilities or take for granted why we craft things the way we do.

I also believe there is room remaining to explore new designs and theories in today’s knifemaking. We can find new ideas and inspiration from places we don’t expect. With the ever-changing laws and shortages of materials such as stag and ivory, we may be wise to consider creating a market based on a process we develop using otherwise unexpected, but available, materials and techniques. This requires time and risk. Are we willing to apply time and effort to follow through with a concept without certainty that there will be a payoff? Is the payoff worth it in monetary or cultural dividends? One can really never know the answers to such questions, and those possibilities were not a serious factor in my efforts.

The X-Rhea is the result of having a curious mind and the ability to explore possibilities. It was an idea, turned into a challenge, turned into reality. The simple sequence is available to everyone. Its cultural value is a matter of opinion, but the process of the X-Rhea Knife shows that new and interesting ideas can be pursued in knifemaking.

Also Read:

- Ballistic Knife: The Most Illegal Knife In America

- Spike Tomahawk Reviews: RMJ Tactical, Cold Steel, SOG, Browning

- A Quick History Of The Tomahawk In The United States

- 11 Tips For Starting A Knife Shop At Home

BLADE’s annual Knife Guide Issue features the newest knives and sharpeners, plus knife and axe reviews, knife sheaths, kit knives and a Knife Industry Directory.Get your FREE digital PDF instant download of the annual Knife Guide. No, really! We will email it to you right now when you subscribe to the BLADE email newsletter.

Click Here to Subscribe and get your free digital 2024 Knife Guide!