In the author’s view, the Carrigan has tells that prove James Black made it.

The work of James Black is iconic. Once you’ve seen one of his knives, you’re not likely to forget it. While a casual observer sees a steel blade that’s well formed and a coffin-shaped handle with black walnut and silver trim nicely complementing each other, informed observers see much more.

Consider yourself more than just a casual observer. You study the knife in every detail. A steady stream of questions begins to cross your mind. You may contemplate the time period, the location and the tools by which the knife came to be.

Why did the knifemaker do this? What were his thoughts when doing that? What factors prompted the design? What subtleties of design did Mr. Black discern and were there any he learned along the way?

I am not a casual observer when it comes to the work of James Black. In fact, I am among “the birds that have flocked together” to study his work. Our group has been studying and gathering data to serve as a baseline for future revelations that may occur pertaining to historic knives. The database can be used to aid in authenticating existing as well as newly discovered knives thought to have been made by Black.

While our group includes collectors, engineers, historians and archaeologists, it also includes knifemakers. The perspective of each adds invaluable insight to the discussion. And oh, what a discussion it is!

What Is The Carrigan Knife?

For several years I was fortunate to have been the resident knifemaker for the Historic Arkansas Museum in Little Rock, Arkansas. It is a rich environment to learn and observe examples of historic knives, among which are some examples of Black’s work. Noteworthy among those is the Carrigan Knife.

Its historic provenance is solid, pointing directly to Black as being the maker. Since Black did not mark his work by stamping his name on it, the reliable historic provenance of the Carrigan Knife is of even more importance—in fact, it’s pivotal to the attribution of any other possible Black knives. Once determined to be authentic, the other knives in the museum’s collection, or elsewhere, can be attributed to Black as well.

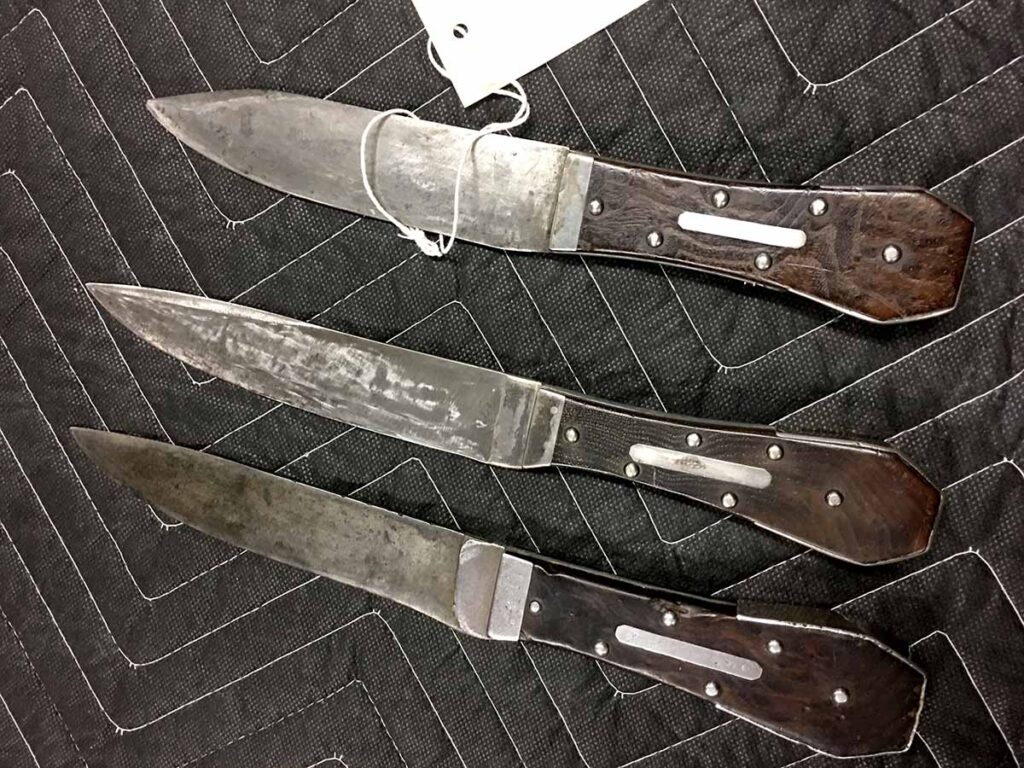

Consider Image 1 (top of page). The knife in the middle is the Carrigan, known to have been made by Black. It has provenance. What about the ones on either side? Do they have rock-solid provenance? No.

In the eyes of the museum curatorial staff as well as in the context of this discussion, an object’s provenance is important. However, some of the knives attributed to Black, while not having direct provenance, have circumstantial provenance. Does this lessen their value in the historical narrative? No. If determined to be authentic, they are just as important. Even a newly discovered knife with no provenance at all may indeed be authenticated to have been made by Black.

Being able to determine the authenticity of a possible Black-made knife, apart from provenance, would require an examination of the knife. The examiner would need to have intimate knowledge of details and factors unique to Black’s body of work.

In Image 1 you can’t help seeing the obvious relationship between the three knives. While they are not identical, they are so similar that it would be logical to assume they were made by the same hands. While those things are compelling to the belief that Black made all three, much more must be considered to authenticate a knife as his work. Some of those considerations follow.

Any maker’s work, whether currently or in the 1830s, will exhibit common features that, in some way, set the work apart as different from others. Some features may be noticeably subtle and some radically bold. Bold features can be imitated to a degree by others. The subtle features often go unnoticed and are much more difficult to imitate. Black’s body of work exhibits several features that tie the individual knives together circumstantially. Some features are subtle, some bold.

In Image 1 you can easily observe the bold features common to each individual knife, such as the dark handle scales, the silver trim, the coffin-shaped handles, etc. However, to authenticate them as being made by the same maker requires familiarity with that maker’s known body of work and an opportunity to document the features.

The features may be construction techniques or tool marks that are the same from knife to knife. Documenting the common features involves quite a lot. It implies that multiple knives are closely examined for these common features. In some cases, the common features can only be seen through modern technology such as X-rays or other forms of testing.

It is not known how many knives Black made but there’s enough in existence to create a problem of logistics. The knives that are thought to be authentic Black knives are scattered over several states. Getting them together has been tough but we’ve had some success thanks to the knives’ respective owners. The trust and support they’ve shown to the research group is very gratifying.

As you probably have noticed I’ve been very careful with my words since it’s not my place to share too much out of respect to the owners. Some details that are important in matters of authentication shouldn’t be divulged. Lack of these invisible details wouldn’t prevent a modern maker from faithfully reproducing a knife of the style. Remember, imitation is flattery but counterfeiting is illegal. Counterfeiting has been done and there are cases where collectors have been duped. Makers should always mark their work.

Tells Of An Original James Black Knife

All this said, there are things “invisible” that we can discern by observation. In Image 2 (below), an illustration by Steve Hotz, notice that the construction assembly of the Carrigan Knife is comprised of three basic layers: the blade and two handle scales.

While there are three basic layers, each layer can have other parts that contribute to the overall knife. For example, the blade’s tang has additional pieces of silver: one on the ricasso and one each wrapped around the top and bottom of the spine. These serve as a soft bed for the scales to sit on. While thin, these wraps of silver can be filed flat for a good fit of the right- and left-hand scales. They extend back to where the maker chooses to put the silver pommel wrap. The blade tang is also bored for the pin holes to attach the scales. Moreover, the scales have front caps that are flush fit so the scale will lay flat, as well as escutcheon plates apparently individually mounted to the scale independent of the layer’s assembly. When the three basic layers are completed and prepared sufficiently, the scales, which are drilled to fit the tang, can be assembled to the blade and the capped pins installed as well as the pommel wrap.

What I’ve described is the general assembly of Black’s Carrigan Knife.* The entire blade’s steel tang is covered by a protective layer of silver along with the wood scales. Considering the lack of modern epoxies and rust-resistant steels, I consider Black’s logic and resourcefulness very impressive. He strategically placed the silver on each of the three layers so that, when assembled, they meet and provide protection for the knife’s steel full tang, as well as an aesthetically pleasing appearance.

Historically, a blacksmith shop may have had a post drill and some early machinery available. I can reasonably assume that Black had some of this equipment too, but I have no way of being sure. Where we today would likely grind a part, Black may have filed it. To save filing he probably forged very close to finish before filing. We today may skip the forging stage entirely if required and still be able to reproduce a close facsimile of his knife. For every step of his process, we bladesmiths and/or knifemakers can transpose a modern technique or tool.

Black’s process was an interactive, emergent one. The second step emerged from the first. The third step emerged and interacted with the first two steps, and so on. In other words, it was not precision technology as we commonly see today where the parts can interchange from one knife to the next. Emergent technology enabled a craftsman to create complex designs with a reasonable expectation of consistency, albeit not precision.

Again, study the three knives in Image 1. Although they are not identical, you can see the family resemblance. It was a structured process that was organized to lead to a predictable result. On top of that, Black was taking only three materials—steel, wood and silver—and creating a process that makes sense. Considering the relative lack of resources and technology, I think he did well to even create a knife. But he did much more.

When thinking of Black’s work, think not only of his knife design but his process design. It’s his process design that made his knife design repeatable. Modern knifemakers can learn from him in that regard.

Three Questions To Consider

In closing, following are three questions to ponder. The first two are for all of you and the third is for the bladesmiths and/or knifemakers among you.

- If given a limited number of resources, would you be able to make a knife?

- If given these limitations, would you be able to design a knifemaking process?

- In your knifemaking endeavors, how much of your process is an imitation of others and how much is yours?

*Author’s note: I have not gone into detail on each of the individual parts and how Black performed these steps for two reasons: 1) I can only observe the appearance of the knife and speculate on his exact techniques, and

2) It would only serve the purpose of counterfeiters.

Editor’s note: While BLADE® recognizes the author’s superior knowledge concerning the provenance of the Carrigan and other knives attributed to James Black by the author and others, BLADE continues to stipulate that for BLADE to recognize that a knife was made by a specific maker, the knife must bear the specific maker’s name or mark. The presence of such a mark does not necessarily prove the knife was indeed made by the person or company marked, but the absence of a mark is enough to preclude BLADE from attributing the knife’s make to any person, company, etc. Since, as far as we know, Black did not mark his knives, BLADE does not attribute the make of any specific knife to him. That doesn’t mean BLADE is right or wrong, it’s simply our policy concerning the matter. To be both fair and accurate to all, it is a policy we apply not just to Black but to all knives and all knifemakers.

More Knife History:

- Antique Switchblades: World War II And Beyond

- American Knives: Legendary Designs From The Land Of The Free

- Military Knives: Soldiers’ EDC From The Past 50 Years

- BLADE Magazine 50th Anniversary: Knife Industry Milestones

BLADE’s annual Knife Guide Issue features the newest knives and sharpeners, plus knife and axe reviews, knife sheaths, kit knives and a Knife Industry Directory.Get your FREE digital PDF instant download of the annual Knife Guide. No, really! We will email it to you right now when you subscribe to the BLADE email newsletter.

Click Here to Subscribe and get your free digital 2024 Knife Guide!