“A Hint of a Curve Looks Better than a Curve”

Of the assorted American Bladesmith Society-sanctioned knifemaking classes I’ve attended, many pertained to the construction of a well-made knife. In one class, the subject of line and flow was a topic.

An ABS founder and a BLADE Magazine Cutlery Hall-Of-Fame® member, B.R. Hughes said, “A curve looks better than a straight line”—pausing for effect—“and a hint of a curve looks better than a curve.”

The human form and other objects in nature often have been used to illustrate proper execution of line and flow. Some of the simplest of things common in everyday life are there for our benefit if we would notice.

Taking Cues from Nature

An unfurling fern, drifting snow, a vine climbing to the sun—these things look alive and give the impression of fluidity even though they are at rest. Consider a falcon’s dynamic grace. Simply when perched it looks designed for motion. These are things the great masters studied and emulated, often applying mathematical formulae, yet concealing any and every hint of math within the object’s overt beauty.

We are all “wired” to be attracted to certain combinations of lines that flow into the whole dynamic appearance of an object, whether a person, a falcon or a knife.

Knifemaking long has been elevated to an art form. It’s a natural medium to express artistry in a functional tool. Knifemakers are the formulators, mechanics and artists who create from raw materials something static that also has dynamic character. It looks like it wants to be moving even though it’s not. Remember the falcon?

The object of this brief dissertation is to help makers wanting to improve their work find a perspective. I say “a perspective” knowing it would be uniquely each maker’s since each maker is different and can’t see things exactly the same. Michelangelo’s perspective was not Leonardo da Vinci’s and vice versa, but each developed an eye for his own work.

Also, it may not be possible to explain to another exactly how to have an eye for line and flow. My attempt is simply to rationalize that it is possible to cultivate its development.

Developing an Eye for Line and Flow

If this development is possible, then each maker should ask, “How can I cultivate it in my own work?” Considering the question requires a level of honesty that some are just not willing to attach to something they mistake for “a knife.”

Indeed, the question pertains to the process rather than the product. It is a way of thinking about the craft and not simply “a knife.” That mistaken thinking will never allow a person to elevate knifemaking to an art form, and it can’t help but to manifest itself in a maker’s work. Fortunately, there are many examples of makers who have enhanced their natural talent by honest self-improvement.

What do some of the world’s best makers do to cultivate their eye for line and flow? Where do they look for inspiration? What influences have shaped their perspective?

How the Master Smiths See Line and Flow

“Many of my best knife designs were inspired by nature,” such as a lily, a bird’s wing and vines, stated ABS master smith Jerry Lairson. “I think it’s good to follow a theme throughout the knife. An example is the fluting on French flintlock pistols combined with the other parts of the gun to create flow. If you see something you like, even if it doesn’t pertain to knives, try to use it as a theme to design a knife. If a knife is decorated with engraving, carving or filework, it should enhance the flow and line of the knife rather than

compete with it.

“Sometimes I see things in museums that have nothing to do with knives but have graceful lines that can help design a knife that flows. How a knife design starts and stops at the point and butt has a lot to do with flow. Sometimes flow is hard to achieve even when you have a good design in your head.

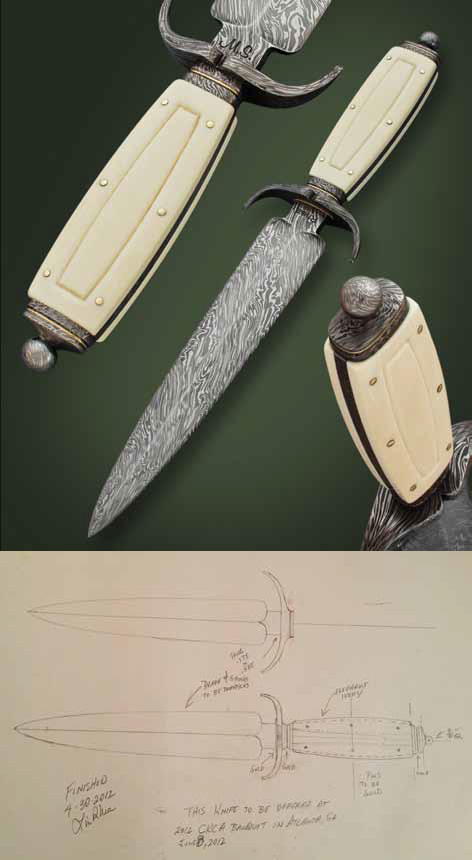

“When this happens to me,” Jerry continued, “I put it on paper and if it doesn’t flow, I start trying to figure what doesn’t look right. I always design a knife on paper. Once I have the general shape I want, I start changing things one at a time until it starts to flow. Sometimes one small line that isn’t right will throw the whole thing off. Sometimes simpler is better.”

ABS master smith Rodrigo Sfreddo pointed out that good line and flow is the “obligatory minimum” for any custom knife.

“What makes a knife more desirable than another? Good design,” he began. “Nobody spends hundreds or thousands of dollars on a knife just because they need a good knife for camping or cooking; they’re buying for collecting because [the knives] are beautiful, so good design and aesthetics are of the utmost importance.

“I always say to my students to think about the beauty when planning a knife, not what is easy or what not to make. It’s very easy to make the same blades, guards and handles we’ve already made and seen. The result is just a combination of designs we’ve already used before—one blade just like the one we made some time ago, combined with another guard we made in another project, with another handle, and even the filework, just new combinations of our same old ideas!

“That’s why it’s so important to pay attention to anything that’s beautiful and has great design,” Rodrigo maintained, “like cars, antiques, furniture, architecture and so on. We must refine our taste on everything so it will reflect on our work. It’s unbelievable how we can figure a knifemaker’s characteristics from his work, especially if he’s ‘thinking’ about his work or just following the crowd.”

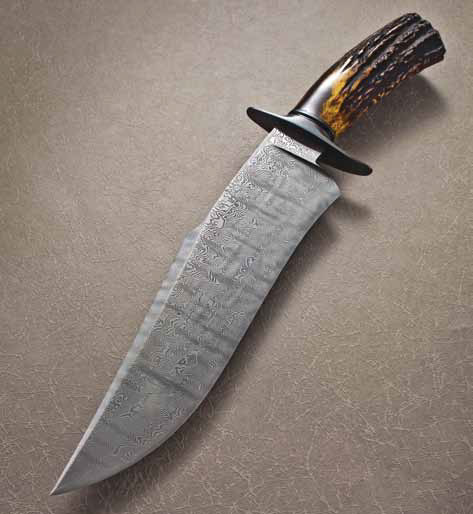

ABS master smith Jason Knight’s knives are known for their superlative lines and great flowing execution. He spoke of the ancient ways of looking at and designing things, saying they work and that he won’t try to change them. He described his method as a “way of seeing” involving his eyes and his heart. He pointed out that makers have choices in materials that offer color and texture.

“Materials can limit or enhance design. Some designs might look cool but don’t work well. Usually,” he qualified, “if it looks good, it works well.”

He recommended taking inspiration from other art forms, such as sculpture and woodworking, adding that he likes curves and both long and subtle arcs.

Open Your Eyes

Trying to express the causes and effects of something whose nature is so intangible requires some degree of interpretation, and I’m not sure I am the one to carry this task to completion. However, most makers are in the same boat. Who would have thought so much would be involved in the making of a knife?

Do I understand it all? Not by a long shot. Am I overthinking the matter? Maybe. But it could be that considering these points will help my perspective become a little clearer. Besides, considering that the above three makers give serious attention to advancing line and flow in their work, I feel I’m in good company.

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

BLADE’s annual Knife Guide Issue features the newest knives and sharpeners, plus knife and axe reviews, knife sheaths, kit knives and a Knife Industry Directory.Get your FREE digital PDF instant download of the annual Knife Guide. No, really! We will email it to you right now when you subscribe to the BLADE email newsletter.