Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the May 2002 issue of BLADE magazine. It’s the first part in a three-part series about The Iron Mistress. You can read the entire series, plus 10 years of back issues, in this digital collection.

A “Choicely Good” Knife

“It will never be again,” concluded its maker, James Black, as he stepped forward added, “I fused into it a fragment of a star. For better or worse, that knife has a bit of heaven in it, or a bit of hell.”

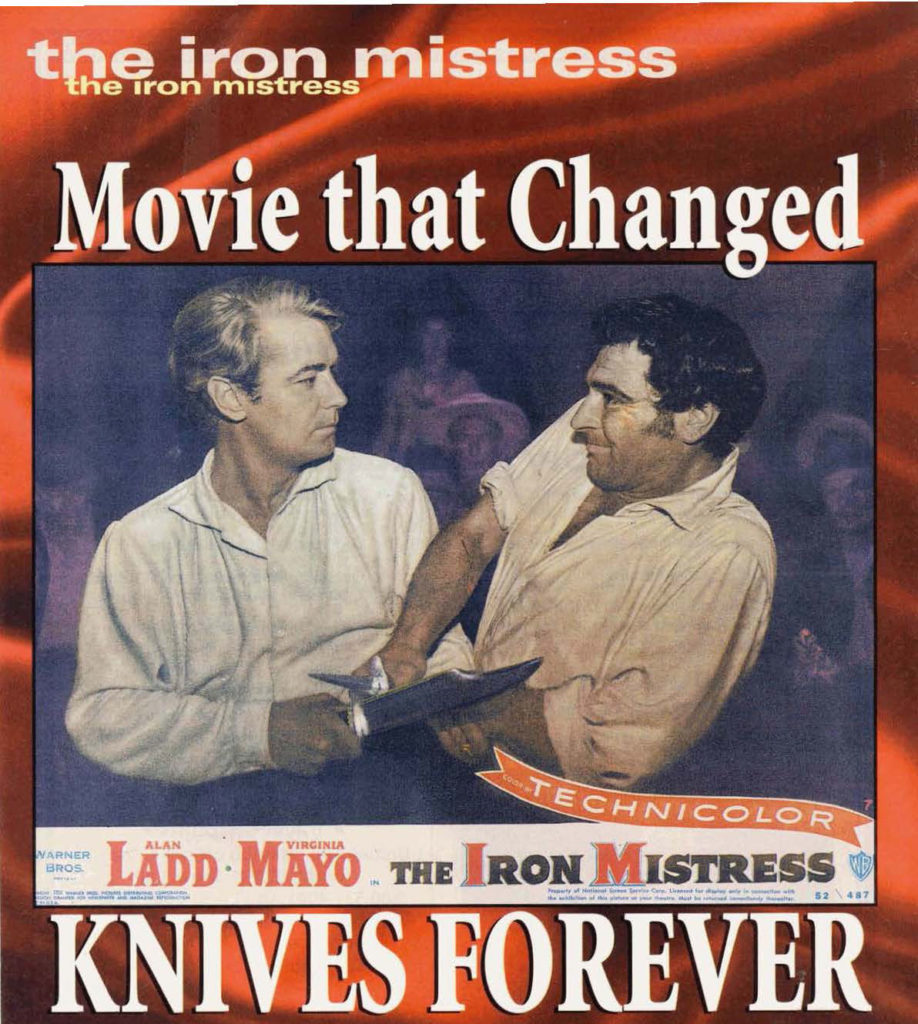

With these words, actor Alan Ladd, as Bowie, and David Wolfe, as Black, summed up 50 years ago in Warner Bros.’ film version of Paul I. Wellman’s best-selling 1951 novel, The Iron Mistress, what was to become, for better or worse, the world’s best known and, in some cases, favorite interpretation of Jim Bowie’s knife.

An Enduring Mystery

Actually, they had every right to do so, since whatever knife, or knives, the historic Jim Bowie may have owned disappeared after his valiant death on March 6, 1836, in the crumbling mission-fortress of San Antonio de Valero, nicknamed the Alamo, at the hands of hordes of Mexican soldiers.

This event, while giving Bowie immortal fame, unfortunately caused the exact style, mountings, dimensions and identity of whoever made his equally legendary knife to be argued by his family, including older brothers John and Rezin, and their descendants, as well as friends, historians, writers, collectors and fans ever since. Once Warner Bros. acquired the rights to Wellman’s novel, the chore of through the existing research and period bowie knives in order to arrive at a credible visual of Bowie’s blade was added to the other production concerns, such as the casting of the larger-than-life Bowie himself and deciding exactly how much of Wellman’s sprawling, epic novel to film.

Not only was the book colorful, befitting the real life Bowie, but it was also expensive in film terms. There were pirate fights, knife fights, Indian fights, fistfights, gunfights, and the Texas War of Independence from Mexico, culminating with Bowie’s force of possibly 200-260 men at the Alamo against an army of thousands.

As with his knife-and since the historic Bowie left no written record an his life known of thus far. The historians who preceded Wellman had to piece together all the salient events leading up to Bowie’s untimely yet heroic death. They were far from successful in many instances, so much so that Bowie and his knife, or knives, have been shrouded in legend almost from the day he died, and in some cases before then.

In choosing a fictionalized rendition, Wellman obviously not only felt that it wasn’t necessary to document his sources, but decided to incorporate all the fragmented, and sometimes inaccurate, 19th-century accounts on Bowie into a cohesive narrative, even if the author had to invent characters to bridge the events.

Adapting the Novel for the Silver Screen

The fact that Wellman and Warner Bros. did it so convincingly has caused succeeding writers and people who should know better to believe that Bowie’s femme fatale in the novel, Judalon de Bornay, played by the gorgeous Virginia Mayo in the film, was an actual person and that Bowie’s knife was made from a fragment of a star, or to be more specific, a meteorite.

Furthermore, not only did the book and film add more myths to Bowie’s already jam-packed legend, but there are those who are just as unsure as to who made the knife for the movie and the circumstances surrounding it as they are about the knife, or knives, Bowie wielded in real life. For years, many believed that John Nelson Cooper made The Iron Mistress movie knife.

Others insisted it was Bo Randall. Only last year, a well-known cutlery writer indicated that Jimmy Lile was the artificer. All three makers drafted versions of it on request after the movie was released, but not for the movie itself. Still others are traipsing through the Smithsonian Institution to find the actual prototype on which the knife was supposedly based.

Fortunately, unlike the historic Jim Bowie, the prop knives and the primary source records regarding the film still exist, and those involved with the production lived long enough to share their insights.

Setting the Stage

Turning the clock back to 1951, these records show that Wartier Bros. initially considered John Wayne, William Holden, Steve Cochran, Burt Lancaster, Jeff Chandler and Charlton Heston to play the larger-than-life Bowie.

However, at the time, Wayne was trying to get his own Alamo project going, which involved Bowie as a central character. Though he was starring in other films at Warner Bros. during the period, where his contract was split three ways between Warner Bros., RKO and Republic Pictures, Wayne was mistakenly led to believe by Republic’s president, Herbert J, Yates, that Republic was committed to also allow him to direct his Alamo film, as well as produce and star in it.

At the same time, while Warner Bros. was considering other options, 20th Century Fox president Darryl F. Zanuck announced that, “There aren’t any box office stars anymore except John Wayne and Alan Ladd.”

It’s interesting to note that Ladd’s 10-year contract was coming up for renewal at Paramount Pictures in 1951. Upset with the roles he was getting there, Ladd announced that he would be taking offers from other studios.

Team Iron Mistress

With these factors in place, Warner Bros. wooed Ladd away from Paramount, as well as from Fox who was also angling for him, and gave him the Bowie role to showcase the studio’s new contract with the star.

Warner Bros. then backed the film with a top production team. Besides assuring the studio that Ladd would be a credible Bowie, it was this team that spearheaded The Iron Mistress. The triumvirate of producer Henry Blanke (The Adventures of Robin Hood, The Maltese Falcon, Treasure of the Sierra Madre), director Gordon Douglas (San Quentin, Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye), and art director John Gabriel Beckman (The Adventures of Robin Hood, The Maltese Falcon, Casablanca) would play monumental roles in the finalized film version of The Iron Mistress.

Making The Iron Mistress Knife

With the Warner Bros. research department behind them, Blanke, Douglas and Beckman examined all the then-known accounts and photos of authentic bowie knives. Like Wellman, they also consulted Raymond W. Thorp’s 1948 book, Bowie Knife. In the end they decided to adapt the antique bowie labeled “Fig. 3” in T.B. Tryon’s historical account, American Toothpick, from the April 1941 issue of Antiques Magazine.

It’s interesting to note that they also saw that the knife had a similar blade shape to the 19th-century folding bowie, termed “clasp knife,” with a brass strip on the blade spine in the Smithsonian Institution.

Since Thorp described the brass-strip feature as being on some bowie knives made by one of Jim Bowie’s knifemakers, James Black, and Wellman said that the feature was on the knife Black made for Bowie, Blanke, Douglas and Beckman felt that they had “solved the mystery.”

Of course, other influencing factors included the similarity of the clip point on the knife facing page 97 in Thorp’s book, as well as Tryon’s belief in his American Toothpick article that the knife in “Fig. 3” was the style the historic Bowie used in the Sept. 19, 1827, Sandbar Fight, which initiated Bowie’s fame, and the fact that the brass strip could be traced back to the Highland dirk knives of Bowie’s Scottish ancestry.

Though Jim Bowie’s brother, Rezin, described the Sandbar Knife as having it 9 1/4-inch blade, family friend Caiaphas Ham said it was an 8-inch blade, Thorp described a brass-backed bowie made by Black with a 14-inch blade and Wellman wrote that it was an 1 1-inch blade, the Warner Bros. team compromised on a 10 1/2-inch blade 2 inches wide and 3/8-inch thick tapering to 3/16 inch at the brass back. Beckman then had production illustrator Philip Jefferies do some concept sketches for approval.

Once accepted, set designer Allen Smith drew up the blueprints for the knife. Besides the brass strip on the blade’s back, Beckman’s design included a lugged German (nickel) silver crossguard, a scalloped brass ferrule encasing the dogbone-shaped wood handle that was lacquered black, and a fancy three-piece brass buttcap.

Feeling that the historic Bowie would want his name somewhere on the knife, Beckman designed the letters “Jim Bowie” in script to be cut out of sheet brass. This was laid over an oval nameplate made of a cream-colored Formica to simulate ivory. A strip of brass bordered the nameplate and the entire ensemble was inlaid in the hahdle on the trademark, or reverse, side of the knife.

Flanking the nameplate were two brass rivet heads, each in the shape of a five-petal rosette. However, only the two rosette rivet heads appeared on the opposite, or obverse, side of the handle, not the nameplate.

Beckman then gave the blueprints to property master Ed Edwards who, in turn, assigned prop maker Arthur Rhoades to execute the finished version. Using automotive spring steel, Rhoades ground out the blade and brazed a strip of brass along the back. A plaster cast of Ladd’s hand was given to the prop maker prior to carving the wooden hand1e. This caused Rhoades to alter the blueprints slightly by lengthening the handle to 5 31/4 inches and the crossguard to 3 1/2 inches for an overall length of 15 5/8 inches, or the entire knife.

BLADE’s annual Knife Guide Issue features the newest knives and sharpeners, plus knife and axe reviews, knife sheaths, kit knives and a Knife Industry Directory.Get your FREE digital PDF instant download of the annual Knife Guide. No, really! We will email it to you right now when you subscribe to the BLADE email newsletter.

Click Here to Subscribe and get your free digital 2022 Knife Guide!