BY LEON KAPP

The great World War II Japanese swordsmiths, war sword souvenirs and more

Kurihara Akihide established the Nippon To Denshujo. Akihide was a member of the Japanese Diet or congress. The Diet asked him to help make swords and train swordsmiths. He set up the Nippon To Denshujo in Tokyo in 1933 and hoped to train about 1,000 swordsmiths. His first student was Yoshihara Kuniie, the grandfather of perhaps the today’s foremost living swordsmith, Yoshindo Yoshihara. Kuniie later became head of a sister forging organization in Yokohama, and the head of the Army Forge in Tokyo. Kuniie’s brother and son (Yoshindo’s uncle and father) also joined the Denshujo and began making swords at this time.

The Denshujo’s students usually took names beginning with the character Aki from the founder Akihide’s name (such as Akifusa, Akimitsu, etc.). Kuniie originally signed with the name Akihiro but soon began to use the name Kuniie, as did Yoshindo’s father (Yoshindo’s father was the second-generation Kuniie). The swords from the Denshujo are of very strong interest to collectors, as well as any Yoshihara sword from this period, and also any swords made by the Denshujo’s chief instructor, Kasama Shigetsugu, and its founder, Kurihara Akihide. A surprisingly large number of Japanese smiths working today can trace their professional lineage to someone who worked at the Denshujo from 1933 to 1945.

SEKI CITY

Seki was home to 350 licensed swordsmiths as well as a large number of associated craftsmen. The city had a population of around 30,000 and about half of them probably were involved in sword production, polishing and mounting. In the 1940s, Seki shipped about 18,000 mounted swords a month to the military organizations. Traditional tama hagane swords comprised about 6-to-7 percent of the output. Many others were made from puddled steel, and cheaper swords were made from foundry steel and salvaged structural steel. The leading smiths in Seki commonly signed with names beginning with the character Kane, such as Kanefusa, Kanenobu, etc, and many of the resulting swords are of interest to collectors today.

The Manchurian Railway Co. in Manchuria made specialty steels and used them for swords. All the swords were signed indicating they were made by the Manchurian Railway Co., and very rarely have an individual swordsmith’s name on them. The swords appear to be made of several types of proprietary steels folded and forged together. They almost always have a simple, straight hamon.

There were many very good smiths scattered around Japan whose work is valuable today. Some of them included Nagamitsu in Okayama, Takeshita Yasukuni in Hokaido, the Horii family in Hokaido, the Gassan family in Osaka, Minimoto Yoshichika, Masakiyo, Takahashi Yoshimune, and many others, as well as swords signed Koa Isshin Mantetsu saku made by Manchurian Railway Co.

All Japanese sword production stopped in 1945 and was illegal until the U.S. occupation ended in 1953. Sword production then resumed slowly and, by 1964 when the Tokyo Olympics was held, there was finally a healthy market in Japan again for newly made swords, or gendaito.

WAR-ERA KOSHIRAE

The original Westernized koshirae used by the Japanese military closely resembled 19th-century European-style mountings with slight adaptations to fit Japanese swords. Around 1931 or 1932, new koshirae styles were adopted and are the ones seen with most World War II Japanese swords. The new army mounting was closer in form to the traditional Edo-period-style koshirae. It could properly contain a traditional Japanese sword and allow it to easily be used in the traditional manner.

The navy also adopted a new koshirae at about the same time, and is how surviving Japanese World War II naval swords commonly are mounted. The army scabbards were usually covered with a thin sheet of metal lacquered a shade of khaki. There was a traditional sword guard or tsuba, and all the traditional metal fittings were present. The navy scabbards often were covered with sharkskin or rayskin, with all the traditional metal fittings and tsuba in tow, too. In 1944, a new model army koshirae appeared which seems to be an evolution of the 1932 version. Generally, swords that appear in these types of military koshirae have blades of tama hagane or puddled steel and are generally well made.

JAPANESE WAR SWORD COMPARISONS

In general, Japanese sword blades of the 1930s and 1940s are well constructed. They feature steel that was forged proficiently and a visible jihada if they receive a new, quality traditional polish. However, in comparing World War II-era swords to older swords and to swords made after 1960, there are clear differences.

The differences arose from the lack of traditional tama hagane for the swords, and pressure to produce a large number of swords in as short a period of time as possible. Using tama hagane is very time consuming and requires expensive raw materials and a large amount of forging time. Consequently, when comparing swords from World War II to other periods, they appear to be stout and heavy with a strong amount of tapering in the width of the blade from the hilt to the point (typically about 20 to 30 percent). In addition, the hamon are usually straight, or are straight and have simple projections (ashi) extending to the edge, or are simple gunome or regular small loops or waves. This type of hamon is relatively easy and fast for swordsmiths to make.

Using puddled steel avoided the time necessary to make tama hagane and to fold it 12 times to give the steel the proper qualities. In addition, the puddled steel (and all swords not made from tama hagane) was made of a single piece of steel forged to shape. Traditional tama hagane swords are composite structures with a high-carbon outer jacket and a soft tama hagane inner core. This reduced the costs and time involved in making the swords, which was important because officers had to buy the swords from the various forging groups. Typically, a tama hagane sword was twice the price of a puddled steel sword, and the other types of swords were less expensive. Yasukuni swords were traditional and very expensive, and cost about twice as much as a traditional sword made in Seki.

WAR SOUVENIRS

During World War II, many American soldiers simply picked up swords on battlefields. During formal surrenders, the Japanese soldiers surrendered their swords in the field. After the occupation began in 1945, U.S. military authorities went house-to-house to collect all weapons, including swords. In Tokyo, the Akabane Armory was the place where all confiscated swords were taken. At one point, one of the army staff members in charge of the confiscated swords said there was a stack of swords about 6 feet high and 300 feet long. Any U.S. soldier who wanted a souvenir sword simply went to the armory and picked out whatever he desired.

According to some collectors, in the early 1950s there were probably more Japanese swords in the USA than in Japan. As Japan recovered and became prosperous after the war, many of the swords here were bought and returned to Japan.

The World War II era was a unique period in Japanese sword history. The variety of swords made, the excellent quality of the fully traditional models, the somewhat distinct style of the swords, and the very large number made all help to define a very specific period in Japanese sword history.

GLOSSARY of JAPANESE SWORD TERMS

Ashi—simple projections from the hamon extending to the edge of the blade

Gendaito—newly made swords

Gunome—loops or waves in the hamon

Gunto—Japanese Army style of sword mounting

Hamon—temper line

Itame hada—a wood-grain pattern on the blade

Jihada—blade surface pattern

Kaigunto—Japanese Navy style of sword mounting

Koshirae—sword mounting

Puddled steel—steel from railroad rails used to make Japanese sword blades

Tama hagane—traditional steel for Japanese sword blades

Tsuba—traditional sword guard

References: Fuller, R. and Gregory, R. Japanese Military Swords and Dirks, Howell Press, Inc., USA. 1997

Kapp, L., Kapp, H., and Yoshihara Yoshindo, Y. Modern Japanese Swords and Swordsmiths, Kodansha International, USA 2002

Dawson, J. Swords of Imperial Japan, Stenger Scott Publishing, USA 2007

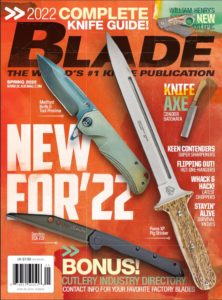

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

BLADE’s annual Knife Guide Issue features the newest knives and sharpeners, plus knife and axe reviews, knife sheaths, kit knives and a Knife Industry Directory.Get your FREE digital PDF instant download of the annual Knife Guide. No, really! We will email it to you right now when you subscribe to the BLADE email newsletter.