Daryl Meier’s star pupil pays tribute to a mentor who taught him oh so well.

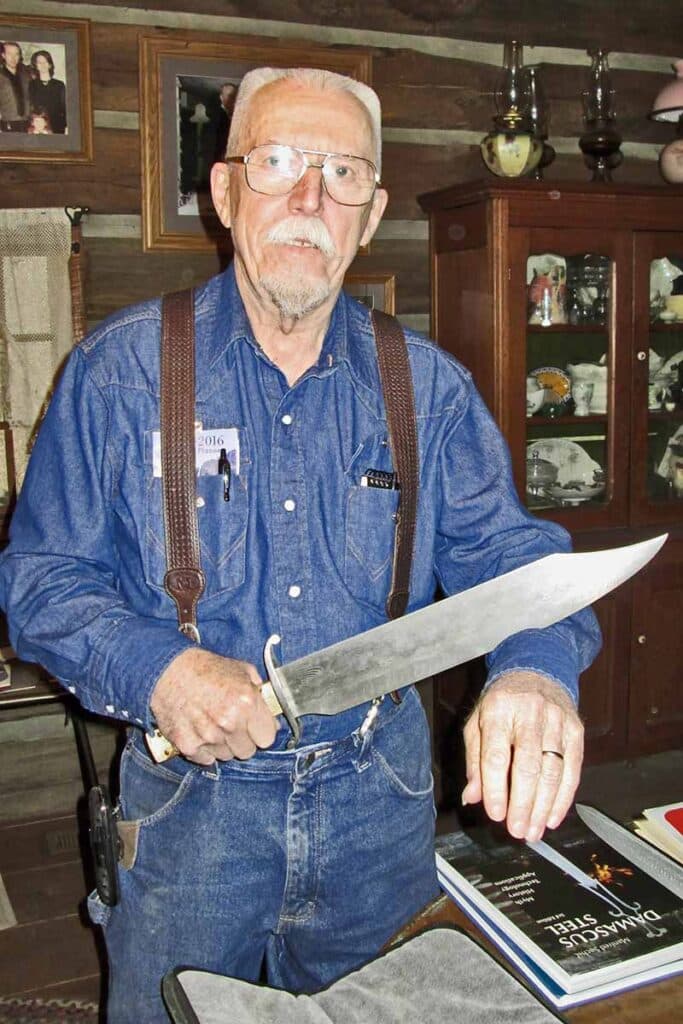

Daryl Meier is a pattern-welding legend. He has influenced more modern pattern-welding experts than almost anyone I know, both in the USA and worldwide.

Daryl was born just outside Carbondale, Illinois. In 1958 he moved into the small city, which is situated in the southern part of the state. There wasn’t much to see in Carbondale back then, though a local blacksmith worked there. It was in the blacksmith’s shop that Daryl developed an interest in forging which influenced his entire future career.

He influenced my work at levels I can’t even begin to explain.

Damascus Knife Renaissance

I started forging blades in 1972. I went to Alfred Pendray’s shop to learn how to forge weld and I was fortunate enough to learn from Alfred’s father, John Pendray, a master ferrier and a great blacksmith. Mr. John took a lot of the mystery out of the forge-welding process. To him, it was quite ordinary. He grew up doing it for a living.

There are many legends about pattern welding that have gone out of favor. It never really did. The history of pattern welding goes back unbroken for at least 2,000 years. Alfred told me that in the 1940s and ’50s, there were probably 40 or so ferriers around Ocala, Florida, alone who were putting tongs and hammers together out of different pieces of scrap steel of different alloys that, when etched, would show a pattern. This indicated the tongs and hammers were pattern welded, as far as I know, a common practice around any blacksmith shop or horse farm back in the day.

Pattern-welded material being used in knives in the USA began getting noticed in 1973. BLADE Magazine Cutlery Hall-of-Fame® member Bill Moran launched it all with the damascus knives he exhibited that year at The Knifemakers’ Guild Show in Kansas City.

Daryle Meier Cutting Edge Damascus

At the same time, Daryl began to put a group of guys together to research pattern-welded steel in Carbondale that included Daryl, Jim Wallace and Bob Griffith. The research involved extremely complex patterns stemming from the Merovingian culture (circa 450-750 A.D.). The pattern-welded material in Europe and Asia had continued to be produced for hundreds of years. There were several European makers in the 1800s and well into the 1940s actively making blades from the material (see “Who Made the First Damascus,” January 2015 BLADE®).

The renaissance in America came in the early 1970s with Moran. A short time later, along with bladesmiths Bill Bagwell and Don Hastings and Cutlery Hall-of-Famer B. R. Hughes, Moran founded the American Bladesmith Society (ABS) in 1976. Moran made some simple pattern-welded knives and reintroduced the material to the knife industry. Through the ABS he spread the knowledge of pattern-welded steel to many.

Daryl and his crew were doing their research on very complex-style pattern welding in the early ’70s. They focused on redeveloping the complex techniques of the ancient smiths. Daryl was a great influence on Alfred Pendray, me and almost every other maker of pattern-welded material. As far as I know, Daryl was the first one who made steel for other knifemakers. There may have been some others making steel for other knifemakers—I don’t know for sure. If there were it was just a handful of guys, maybe a dozen or so, but by the early ’90s there were over 300 such makers producing steel in the USA.

Meier As A Teacher

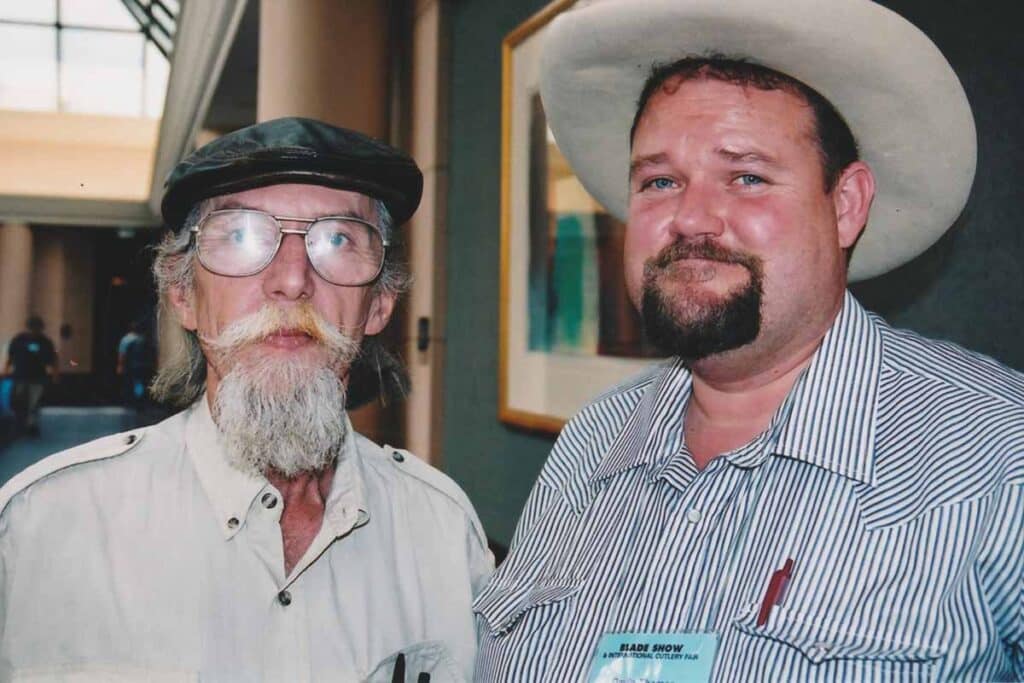

I was extremely excited whenever I had the chance to talk to Daryl. I met with him on several occasions. Pendray and I stopped by Daryl’s shop on the way to a Kansas City Guild Show one year, and we were able to see his operation and gained a lot of useful information from him. Around 1982 I attended a big hammer-in held in Birmingham, Alabama, and Daryl was there. I’d been making pattern-welded steel for a while. I also was doing some mosaic damascus.

Daryl was introducing me to a young man and I’m almost positive the young man was Rick Smith. He came up and they asked me how I did a particular pattern and when I explained how I did it, Daryl corrected me immediately. He said you don’t understand, Rick has his “ticket.” I said what’s his “ticket”? The young man immediately showed me a small slab of mosaic that had beautiful little chrome steps going up to a patterned center and a bar. He and I spent two hours together exchanging ideas. The lesson I learned: there were a lot of people working on mosaic damascus material who I did not know.

Later, as Daryl and I began to work on canister mosaic as a way to get around hot isothermal pressing, I devised a plan to use refrigeration hoses to introduce gas into the canister. I’d worked out this elaborate system with vacuuming and gassing, and, having experienced great success welding with very low temperatures, I could not wait to share the discovery with Daryl. He listened very patiently as I outlined the gear I used and said to me, “Well, what I do is add three or four drops of diesel or hydrocarbon [fuel] to my canister and I don’t have to use all that gear because the hydrocarbon will scavenge all the oxygen”—which is the bad thing, so my bubble was burst. It was one of many occasions where I approached Daryl with a new idea and he said either he thought it would work or, “I have a piece of that on my bench from a few years ago.” He has a great method of teaching.

Meier’s As An Innovator

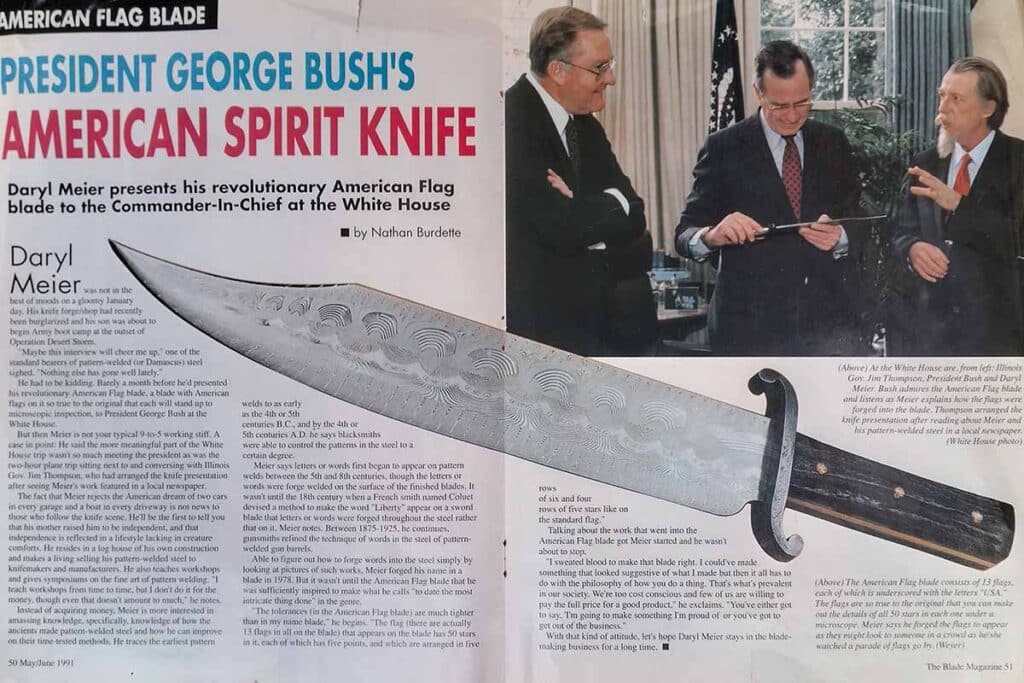

Daryl was a great innovator and about 1990 made a knife called the American Spirit Bowie. Each side of the blade has 13 American flags all along its length with all 50 stars in each of them, and USA reading correctly from left to right no matter which side of the blade you viewed. It took Daryl 18 months and over 800 hours to build the blade, which he presented in person to President George H.W. Bush in the White House (see May/June 1991 BLADE®).

Without doubt, Daryl’s work has influenced more makers than almost anyone else in the modern history of pattern welding. He’s still on the planet and still teaching from time to time. He’s done thousands of workshops over the years that added to the knowledge base of the entire industry. His presence influenced my work in more ways than I can count.

One of the major things he did for me was to push me to the limit of my abilities. After all, doing the easy stuff does not make you grow.

I made several panel blades consisting of all kinds of laminating and experimented with different patterns. I did some electrical discharge machining (EDM) work and Daryl used a bit of EDM in the American Spirit Bowie. He told me I should “make something real,” and that’s how my mosaic damascus shooting scene blade showing the hunter with his dog and the quail in flight came about. It was one of the most intense projects of my career.

Final Cut

Daryl’s students are legion and are some of the very best of the best—all the old guys that are considered the ancients, myself included, and a lot who are gone. A few of us are still around and Daryl was the guy we went to for information. We are standing on the shoulders of giants and one of the earliest ones is Daryl Meier. He may not give you a recipe for a cool new pattern, but he would give you the inspiration to go forward and explore it. He would always say the easy stuff does not make you grow. This is one of the main reasons I still teach because he took time with me.

Thank you, Daryl Meier.

More On Damascus:

- Spectacles In Steel: A Look At Definitive Damascus Patterns

- Stainless Damascus: Challenges In Forging

- Damascus: Mass Producing The Unique Knife Material

- Copper Damascus: An Exciting New Way To Make Knives

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

BLADE’s annual Knife Guide Issue features the newest knives and sharpeners, plus knife and axe reviews, knife sheaths, kit knives and a Knife Industry Directory.Get your FREE digital PDF instant download of the annual Knife Guide. No, really! We will email it to you right now when you subscribe to the BLADE email newsletter.