Making Knives the Old-Old-Fashioned Way

Many knifemakers use today’s best stainless steel money can buy. Other, more do-it-yourself types may scrounge a scrap yard for car springs or ball bearings. Still others go further because all that metal came from somewhere. What if a knifemaker went back to the beginning—starting with the iron pulled from the ground?

In recent years, some smiths have started from square one, pulling raw material from their surroundings to create metal from scratch—just like mankind did for thousands of years. Since the beginning of the Iron Age circa 1200 B.C., man has turned to the iron found in bogs. There, thanks to springs and bacteria, the iron forms into a spongy iron-bearing hydroxide mineral called a goethite.

This renewable source of iron was so important that even the first iron works in America, Saugus Iron Works in Massachusetts, gathered its raw material from nearby bogs. But to turn bog iron into a knife? It’s not a project for the faint of heart.

“You have to prepare hundreds of pounds of charcoal; find, harvest and prepare the ore, build the smelter and then monitor and feed the fire for hours just to produce the bloom,” ABS master smith Kevin Cashen notes. “Then the real heavy work begins of forging it down into a piece of steel that is historically interesting but nowhere near the quality product you get from your modern steel supplier.”

And then there’s the problem of smiths not knowing exactly how the ancients smelted iron.

Darrell Markewitz is a Canadian artisanal blacksmith and historical interpreter of the Vikings who settled in Vineland. He says he is “concentrating on rediscovering lost historic smelting methods.”

For example, he had to make intelligent guesses as to how Vikings tracked time during the smelting process, and how the ancients designed bellows because no bellows from that time exists today.

Sourcing Bog Iron For Making Knives

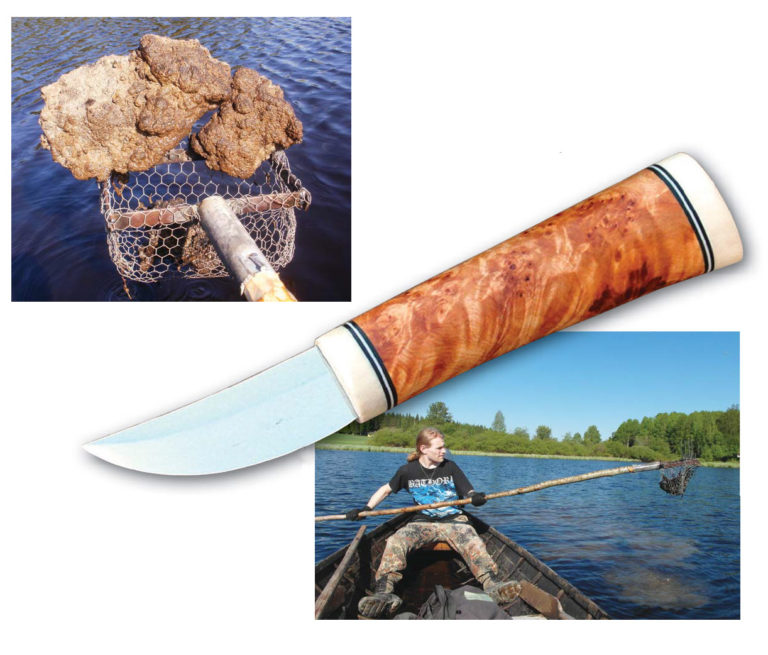

Relatively speaking, Jarkko Niskanen had it easy when he harvested iron out of a bog in Finland. From a boat, the 26-year-old blacksmith simply felt along the bottom of a bog for spongy chunks of material. Markewitz found himself kneeling over a rivulet running through a Canadian bog, feeling for deposits of iron.

Cashen indicates his home state of Michigan is filled with iron. However, only a small portion is bog iron, small chunks of concentrated iron deposited by bacteria on the slow-moving side of streams running through the bog.

“I have found entire cliff faces in the wilds of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula that a magnet will stick to, and huge sections of magnetic black sands on the shores of Lake Superior,” he observes. “But bog iron requires special conditions. I have found some scant deposits locally but not enough to work with regularly.”

There are different kinds of bog iron. All require the same kind of process to turn out a metal. Some types of bog iron react slightly different than others in the smelter, reducing to a smaller amount of usable material, for example. The end result is the same, however: a lump of relatively pure iron.

Once the smith harvested the bog iron, then he cleaned and dried it. Niskanen put his bog iron in a fi re to dry the pieces, and then broke them up until they were small and uniform.

Making Knives Like The Vikings

The process all happens in the bloomery furnace, in what looks like a chimney with an air pipe going into the side to pump in oxygen. It’s a design going back at least as far as Viking times.

“In operating a ‘short-shaft ,’ direct process bloomery furnace, higher air volumes have proven to produce larger, more dense iron blooms—in fact, blooms most like those few found in the archaeology,” Markewitz states.

As the temperatures rise and charcoal continues to be shoveled in, a chemical reaction takes place inside the furnace.

“The ore is always an oxide,” Markewitz continues. “The smelting furnace is a reduction process removing the oxygen from the ore.”

Charcoal produces carbon monoxide, which reacts with the oxidized iron. As oxygen leaves, the iron particles are left behind and fall to the bottom of the furnace. At the interior temperatures, typically something around 2012-2192°F or more, the heavier iron particles are slightly “sticky” and sinter together has they fall, Markewitz adds.

However, bog iron is also filled with non-iron materials, such as ash and sand. In the furnace, the latter liquefy and fall to the bottom of the furnace where they create a greenish-black glass, or slag, in the shape of a bowl.

“The top surface of this bowl is closer to the hot area of the furnace [at the blast level and] so remains a liquid,” Markewitz explains. “If too much of this slag is produced, its interior level can rise up to block the air blast. Before this happens, ideally you want to let some slag run out [by tapping the furnace].”

If all goes well after hours of running the furnace, a ball of iron that is fragmented and filled with pockets of slag, but iron nonetheless, will result in the bottom of the smelter. However, what if the metal workers make the furnace too hot? Then, instead of iron, cast iron may be the result—unusable for forging.

“If the iron particles are made too hot, they liquefy. As a liquid, iron will frantically absorb carbon—so fast, in fact, that the iron almost certainly shifts into a too high-carbon cast iron,” Markewitz states. “This material cannot be forged, and is so hot it usually melts through the bottom slag bowl and collects at the ground level of the furnace … The real truth is that it takes skill and experience not to get high carbon cast iron.”

Most smelts are a community effort. Cashen says his most satisfying smelt was in 2009, one he dubbed “The Matherton Forge Iron Age Challenge.” The goal was to smelt and forge an iron sword in three days as a public demonstration. When Markewitz reenacts Viking smelts, he does it with a team of three other people.

Niskanen took photos of the smelts, which he published online. For ancient metal workers, team effort was out of necessity. After all, bellows are hard to operate for hours at a time to feed a hungry furnace. To keep time, Markewitz’s team chanted, sang songs and focused on heartbeats—possibly historical timekeepers.

“The effective pumping rate was one stroke per second, alternating between the two chambers. Individuals varied on their stroke force [delivery pressure], but averaged 60-to-75 strokes per minute. This was without interruption over the course of the entire firing sequence extending roughly five hours,” he stresses. “We found that to maintain the needed consistency, we needed four individuals working in roughly 10-minute shifts. This labor force needed to be at least semiskilled to the task. This is a requirement totally separate to the needs of feeding and operating the furnace itself.”

Every few minutes, another person would shovel more charcoal into the furnace. Niskanen said he also added crushed limestone to his furnace to enhance the smelting process.

Making Bog Knives

The metal worker is not done once the iron is pulled from the furnace.

“To actually form a solid working bar, the sponge needs to be compressed at welding heat to collapse the voids, squeeze out any glass slag and fuse to a solid block,” Markewitz explains.

While every bloom is different, the smith needs to fold, weld and hammer the metal until it’s a unified—and, hopefully, homogeneous—metal bar.

“And every bloom is a bit different in terms of just how solid it might be at the start, how much slag needs to be ejected, and in what the actual starting carbon content might be,” Markewitz notes.

Then, finally, the bladesmith can practice his craft. For Niskanen, it was only natural to use the iron for a traditional knife. He made a puukko, an ancient Finnish knife (pictured at top of this article).

“Since the Iron Age, the knife has been used as a multifunctional tool in everyday life,” he opines. “And for a hunter it is, and always has been, one of those items you can’t go without into the wilderness.”

Niskanen was there from the beginning, when the knife was only a lump of iron oxide resting on the bottom of a Finnish bog, “It makes the blade really personal,” he says.

Markewitz used his iron as a decorative part of the knife.

“For the modern designs, I use the bloom iron specifically to highlight its unique texture,” he observes. “Blades like [my Hector’s Bane model] have bloom-iron exterior slabs forge welded to a carbon steel core. As with other inset-styled blades, it is this modern alloy core that is forming the actual cutting edge.”

He did it that way because iron blades don’t perform as well as blades of modern steel.

During the Iron Age, Markewitz says iron knives were so soft that users carried a small sharpening stone with them because they had to constantly hone the edges. Nonetheless, some knives no doubt performed better than others.

In a 2013 study published in The World of Iron London, archaeo-metallurgists Quanyu Wang and Peter Crew compared the performance between three knives made from bog iron. Their paper, titled “Three ores, three irons and three knives,” found that the performance of the knives probably was determined by the skill of the smith and the trace elements in the blade, such as phosphorus, which is known for making iron stronger and harder in trace amounts.

However, phosphorous also can make the metal brittle in cold weather. They compared three bog-iron knives by examining the microstructure of the blades and using the knives to butcher a pig.

Wang and Crew concluded their study by writing, “The quality of bloomer iron depends very much on the smelting and refining techniques used, which may not always be recognizable from the structure and composition of the final metal.”

These smiths have more furnaces to build, iron to smelt and possibly blades to make.

“I have studied older bloomery steel, as well as modern smelted materials under the microscope, and tested the properties, and am quite impressed with the smelting skills of the ancients,” Cashen concludes. “Modern academics had only their best guesses about this process until people started actually doing it again, and then we learned how little we actually knew. We are fumbling our way through a process that our ancestors had completely mastered, developed to its highest levels and then discarded in favor of newer and better processes of making steel.”

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

BLADE’s annual Knife Guide Issue features the newest knives and sharpeners, plus knife and axe reviews, knife sheaths, kit knives and a Knife Industry Directory.Get your FREE digital PDF instant download of the annual Knife Guide. No, really! We will email it to you right now when you subscribe to the BLADE email newsletter.