The origins of damascus steel date to as early as 1500 BC.

The allure of damascus steel lies not only in its beauty and utility, but also in the mystique of its origins. Though its development began in ancient times, the word damascus has grown to encompass more than one method of steelmaking, and the earliest method is believed to date back to 1500 BC.

“Damascus steel today can mean at least three things,” explained blacksmith and steel authority Rick Furrer. “First, there’s pattern-welded steel where a bloom of steely irons is welded into a solid mass which then has a pattern. This is the oldest of damascus-steel-making technologies and one which most blacksmiths reproduce with layers of modern steel welded together.

“Second is crucible steel, where the material is fully melted in a container and then the resulting ingot is forged into a bar, which may or may not have a surface pattern. Third is overlaid or inlaid wire, gold, silver, copper or such into a base metal surface such as steel or silver to make a surface pattern. Some call this damascening or damascene.”

Those who have studied the origins of damascus tend to agree that pattern welding did happen first and that it occurred in the Far East, the Indian subcontinent, the Middle East, Indonesia and Europe. Crucible steel production is also referred to as wootz, and its beginning, for some, is easier to pinpoint.

“Some call crucible steel, or wootz, the original damascus, but pattern welding predates it by more than 1,000 years. Pattern welding was in Europe by 1100 BC in Greece and easily by 600 BC in Central Europe. It was very widely spread by 400 BC,” observed Furrer, who in 2011 participated in the filming of a Public Broadcasting System NOVA segment on the famed Viking swords from circa 800-1000 AD with the Ulfberht inscription. The extremely low slag content of the Viking blade steel may indicate a new development in steel processing in Europe, or that the Vikings were forging blades from imported crucible steel.

“The earliest examples of blades made from wootz steel date from around the first century BC,” related ABS master smith Kevin Cashen, “and the oldest examples of the material seem to come from India. While the Indians seem to have been the first to produce crucible steel, they were soon followed by other cultures in the Middle East such as the large production centers in what would now be Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Pattern welding is a trickier process to pinpoint, date or credit to a given culture as it is very old, and just about any people working iron would have produced welded blades on some level.”

Technological Advancements Of Demascus

As technology evolved, production methods improved and fueled the availability of high-quality blade steel. Performance and purpose have contributed to the growth of the industry and the changes in the scale of production through the centuries.

“All of these steel processes were driven by warfare and weapons technology,” noted ABS master smith Steve Schwarzer. “As soon as someone discovered a new method, everybody who wanted to survive jumped on that new method. The moment the local smith developed a method to heat steel to a totally liquid state and control the carbon, the need for wootz and pattern-welded blades fell to the wayside except for the very few who viewed it as art. When the Bessemer converter came into use [in the 1850s] and steel was produced in tonnage at any carbon level desired, there was no need to use the labor-intensive process of making one small piece of material at a time.”

Nonetheless, the craftsmanship and performance of forged damascus is timeless. Modern damascus makers take advantage of improved technology and know-how. The ancient producers worked with basic tools and equipment during a process of both production and discovery. The early makers of pattern-welded damascus combined bloomery steel with varying properties, says Cashen, but the basic tools were quite similar to those used by the modern bladesmith—hammers, anvils and forges.

“One difference is possibly the absence of the fluxes we use today,” Kevin added. “The simple bloomery products of that time period, when worked in a charcoal fire, would weld much more easily and not require the oxygen barriers that we have become so accustomed to today.”

The early crucible process would have involved sealing some amounts of premade iron along with certain organic/carbon-bearing materials and fluxes into a clay crucible that would have been placed in a charcoal-fired furnace, which would usually have been fired by a bellows or natural air drafts.

“The clearest difference in either method now compared to then is the fuel we have at our convenience today,” Cashen commented. “Gas-fired forges and furnaces make the tasks much more convenient than the arduous, dirty labors at ancient charcoal fires.”

Staying True To The Steel’s Roots

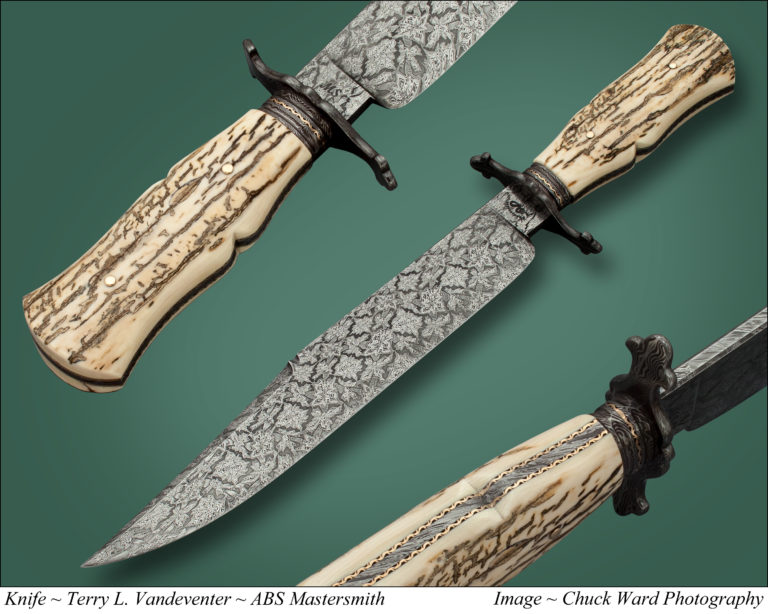

Maybe it is true that the more things change the more they stay the same, particularly as it relates to damascus steel. Surviving examples of either pattern-welded or crucible damascus are impressive in their quality. Modern bladesmiths produce damascus and mosaic damascus/canned steel that simply defies description, the beauty of the patterns speaking for themselves.

Damascus also originally occupied a transitional period in human history. As the Bronze Age waned in Europe, basic iron blades began to appear and pattern welding followed. In the East, iron blades of piled construction were made and pattern welding may have taken place concurrently with it, both being phased out as the crucible process came along. Most experts agree that Europeans were introduced to crucible damascus/wootz during the Crusades.

“With the wootz made by high-temperature smelting in a crucible and forming a cake, bulat or ingot, this ingot was then formed in a very slow, methodical process to produce a beautiful pattern of iron-carbide ferrite and cementite banding,” Schwarzer commented. “This was called watered or damascus steel. It is thought Europeans encountered this material for the first time during the Crusades near Damascus, Syria. Then, this cast material was traded all over the world.”

ABS master smith Al Pendray is well known for his work in wootz steel. Along with John D. Verhoeven, he is listed by the U.S. Patent Office as one of the inventors of “a method of making a steel article having an external surface appearance and an internal microstructure resembling that present on an antique ‘Damascus’ steel sword or blade.” Pendray contends that the earliest crucible damascus was made in Persia and quickly got the attention of Westerners who came in contact with it. “Wootz is ultra-high carbon and will take a real clean edge,” he remarked. “With all the nonmetallic stuff and impurities floating to the top in the process, it’s also a super clean steel.”

But Why Call It Damascus?

As intriguing as the steel itself, the name damascus has a mysterious origin. While the obvious link is to the ancient capital of Syria, the answer to the source of the steel’s moniker is open to speculation.

“One such story maintains that only wootz can be called damascus steel because it was wootz that the Crusaders first encountered in the Middle East, with the town of Damascus being the trading hub for its distribution, thus lending it the name,” Cashen offered. “This theory ignores the fact that there were also damask cloths [with intricate patterns formed by weaving], and that the treatments on many materials involving carving, inlay or otherwise were worked with an intricate flowing or water-like pattern called damascene. It is also worthwhile to note that an old Arab term for water is damas, a coincidence that’s hard to ignore when you consider the number of cultures that refer to patterned steel as ‘watered’ or having ‘watering.’”

Speculating about the origin of the name is intriguing, but Cashen says it is what it is. “In any case, the number of centuries that any steel with a pattern in it has been called ‘damascus’ sort of renders all of these speculative picky semantics irrelevant,” he noted. “Languages evolve, and the word means what it does today. When this is taken into consideration, any steel possessing an induced pattern could be safely referred to as damascus, with pattern welding or crucible steel being the more specific types of patterned steel.”

Finest Blades Ever

As with many highly prized skills, individual bladesmithing and the production of high-quality damascus steel in small quantities has been eclipsed by mass production, given the availability of modern equipment and technology. However, the steel still owes its lineage to the blacksmiths of ancient times. Additionally, today’s bladesmiths keep the tradition and the skill alive like no mass production process can.

“Modern steels are far superior to even the best of these ancient materials because of quality control and repeatability,” Schwarzer mused. “What modern steels don’t have are beauty and the visual fingerprint of the steel artist’s hand. The damascus blades being made in modern times are far superior to the ancient blades because the modern smith is using these very sophisticated steels and modern scientific techniques to produce the finest blades ever made.”

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

BLADE’s annual Knife Guide Issue features the newest knives and sharpeners, plus knife and axe reviews, knife sheaths, kit knives and a Knife Industry Directory.Get your FREE digital PDF instant download of the annual Knife Guide. No, really! We will email it to you right now when you subscribe to the BLADE email newsletter.