Blending old and new, the modern period knife brings history alive in masterpieces.

Historical perspective is a relevant component in just about any undertaking. In the realm of cut, incorporating an appreciation of the past into the work of today brings another dimension to the custom knifemaker’s statement.

Interest in the knifemaking of a bygone era offers a window into the true artistry required to reproduce the knives of yesteryear, particularly with the absence of modern conveniences in the shop. Along with the interest in the historical knife, several custom makers bring famous designs, styles and patterns to life once again in tribute to those who have gone before.

The idea of the period knife blends old and new. “I’ve been making knives seriously since about 2002 when I took a class with the American Bladesmith Society in Washington, Arkansas,” related ABS master smith Lin Rhea. “Joe Keeslar and Greg Neely lit a fire under me and got me on my way. Since then the town of Washington has been like a second home, and I’ve even added to the personal connection between me and the area by interest in one of the town’s historical residents who was also a knifemaker. His name was James Black.”

A resident of Prattsville, Arkansas, Lin gained an appreciation for Black’s distinctive body of work*, using contrasting materials and techniques to create a bold, attractive look. “I’m grateful to get to know Mr. Black by studying his work,” Lin continued. “This intense study led me to try to recreate one of his knives, the Carrigan Knife. The original knife, a guardless coffin-handled bowie, was made by Mr. Black in the early 1830s in Washington, Arkansas. I chose the Carrigan as my first attempt because of its less intimidating size; however, as is often the case I found it to be just as intimidating once I started into the project.”

The original Carrigan includes a black walnut handle providing a nice contrasting background to the coin silver pins and trim. The blade is about 6 inches long, and the overall length is approximately 10.25 inches. The full tang is virtually covered entirely by the walnut scales and the silver wrap.

When Rhea undertook his homage to Black and the Carrigan, he chose stabilized walnut, which he harvested himself several years ago, and trim in sterling silver. He forged the blade from 80CrV2 carbon steel and included at least 30 separate parts while attempting the same techniques used by Black nearly two centuries ago in fastening and assembling the finished knife.

“There is so much to be said about not only this knife but also Black’s work,” Lin concluded. “He was able to create a knife design utilizing only three materials yet impacting the knife world as few others could. His ability to arrange these materials into a functional, long lasting, beautiful tool is only enhanced by the knowledge that he also built in other qualities like moisture resistance, logical assemblage and ergonomics. All of this was done in a historic setting without modern equipment and epoxies. In my opinion, his design is ingenious.”

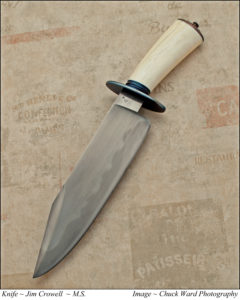

The Gold Rush Period Knife

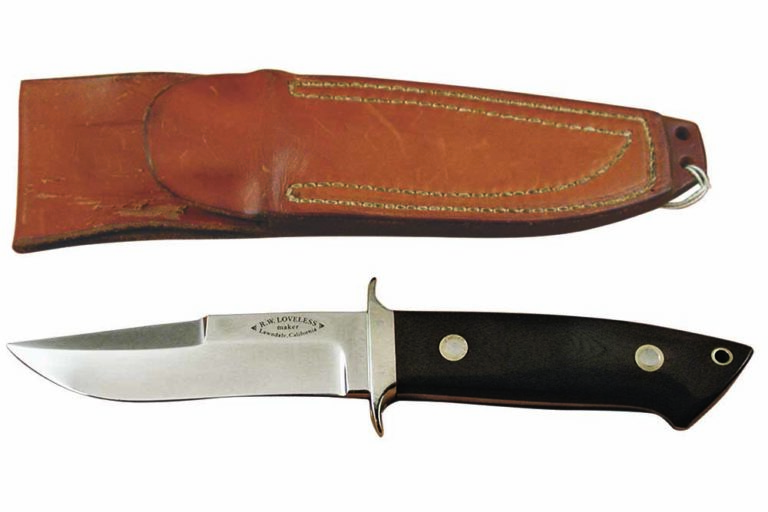

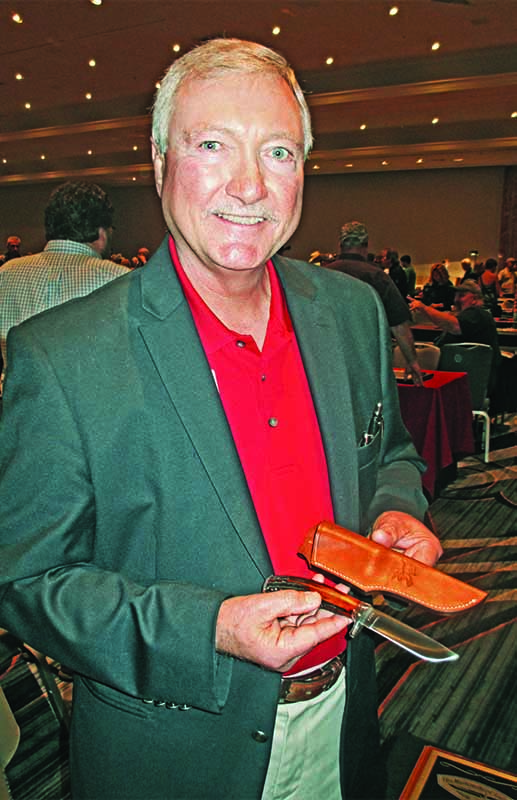

Recently inducted into the BLADE Magazine Cutlery Hall of Fame® (September BLADE®, page 52), knifemaker Jim Sornberger has assimilated his gold and silversmith skill sets into custom knifemaking while helping introduce the modern world to the classic design, luster and embellishment of the Gold Rush era and boomtown San Francisco of the mid-19th century.

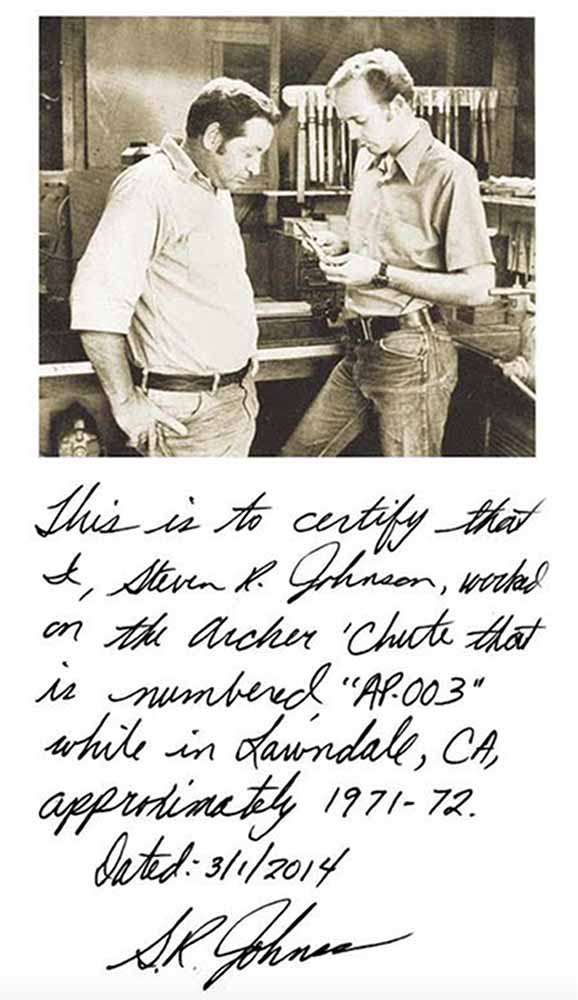

“I’ve been making knives since 1975 with the help of the late Les Berryman, an early Guild member, and with some guidance from Bob Loveless, Herman Schneider and Barry Wood,” Jim recalled. “The last three signed for me to join The Knifemakers’ Guild.”

For Sornberger, the style, embellishment and decoration of the canes, jewelry and knives of the Gold Rush era are most appealing. “San Francisco from 1850 to 1904, the Gold Rush period, was one of the wealthiest cities in the world, attracting some of the greatest artists, jewelers, carvers and engravers to ply their trade to a wealthy clientele. The work done in that period,” he opined, “rivals the best ever done.”

In the knifemaking genre, Michael Price and Will & Finck were among the most successful and prolific of the Gold Rush. Their work remains emblematic of the great migration to settle the American West, and the riches and ruin that were found with the experience.

“Price was Irish, and both cutlery firms hired workers who were English, German and possibly Scottish,” Sornberger explained. “Their dress knives are probably the most embellished American knives made in the 1800s-1900s. The dress knives had two common handles: an interesting, modified coffin shape and a more rounded, subtle taper shape. The blade shapes are spear-point dagger and San Francisco clip spear point.”

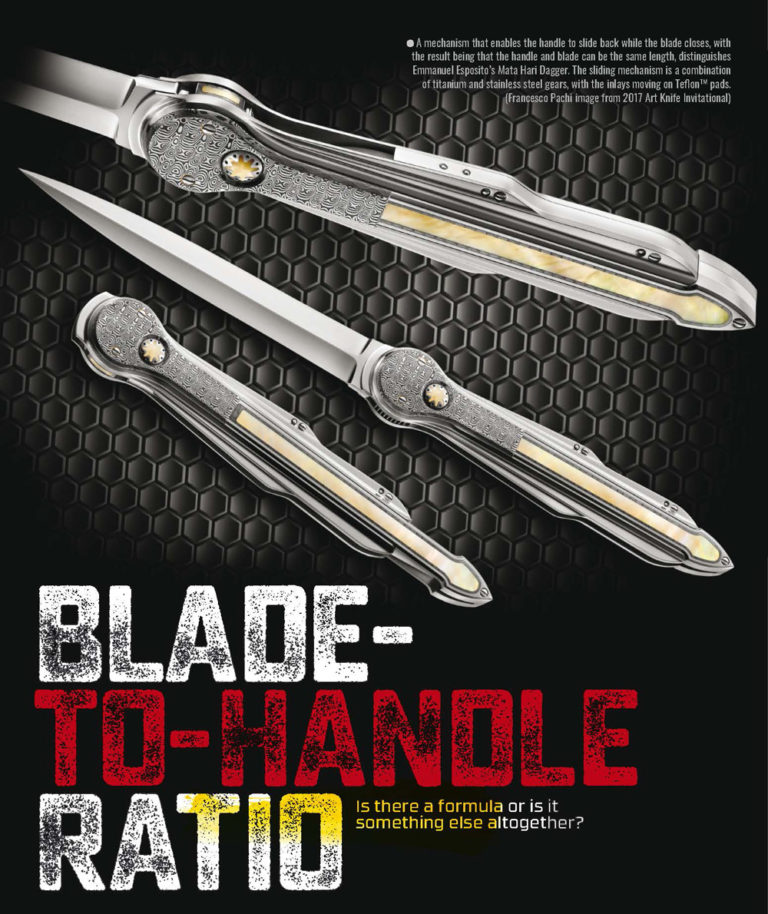

Sornberger is recognized as an authority on original San Francisco knives, as well as the magnificent gold quartz that was used so well by Gold Rush artisans. His modern interpretations of the Michael Price San Francisco/small dress bowie have won awards at various venues, including Best of Show at the 2019 International Custom Cutlery Exhibition in Fort Worth, Texas.

Jim’s dress fixed-blade bowie in the accompanying picture was made with Vegas Forge stainless barstock AEBL and 412 stainless steels, and san-mai damascus steel with a solid core. The guard and wrap handle are in Mike Sakmar mokumé barstock. Jim’s made such handles in gold and silver and nickel silver, also. The inlays are tortoise celluloid and California native gold/gold quartz.

According to Sornberger, the biggest challenge in his stunning creation was grinding the blade to show the distinctive pattern of the shell and the hardened core. The san-mai laminated blade was etched with ferric chloride, rinsed and color set with WD-40®.

Frog Knife

“The style of Michael Price’s work is a really good canvas with flowing lines, and there is a lot you can do with it,” observed ABS master smith Jon Christensen, who is in his 22nd year of making knives. “I wouldn’t call my San Francisco-style knives replicas. I do like to keep to the original form and honor the style of the maker, though.”

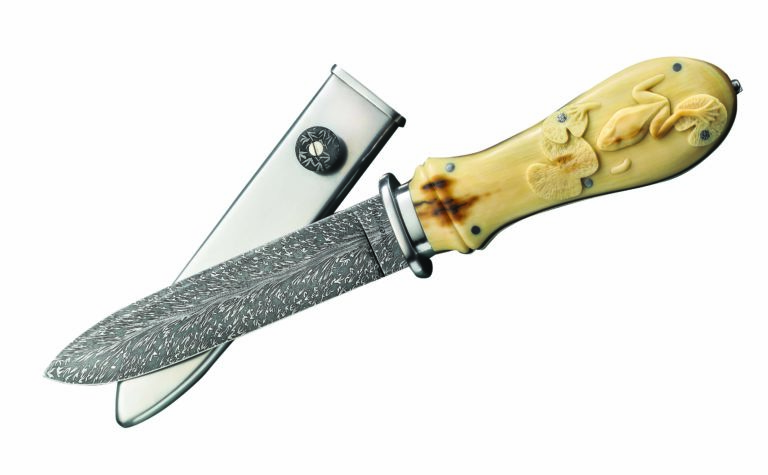

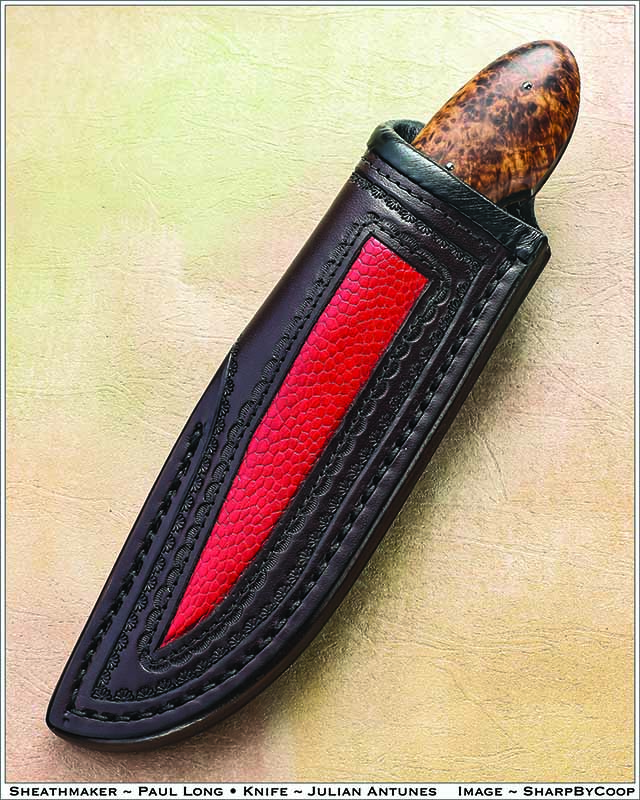

One of Christensen’s most evocative pieces to date is referred to simply as the Frog Knife. However, the piece is far from simple, and Jon manages to convey the spirit of the Michael Price style while also imprinting some of his own personality.

“I built the feathered damascus for the blade with 1080 and 15N20,” he advised. “It’s a canister damascus. I forged the bamboo leaves and placed them in the can, welded it up, reduced it, and feather cut it so it would produce feather-cutting smears and leaves, and form branches to look like a little grove of bamboo leaves.”

The 10-inch knife has a 5.5-inch blade and a frame and sheath incorporating 410 stainless steel. Christensen utilized the “canvas” of the handle to the fullest, carving the mammoth ivory into a pleasing vignette of frogs and lily pads.

“The handle has something of a back story,” he smiled. “I had seen the Poppy Knife that Michael Price made and thought I would do my version. I took the knife to the BLADE Show and it didn’t find its owner. Then, the handle got ruined, and I just took the opportunity to rehandle it with the frogs and lily pads.”

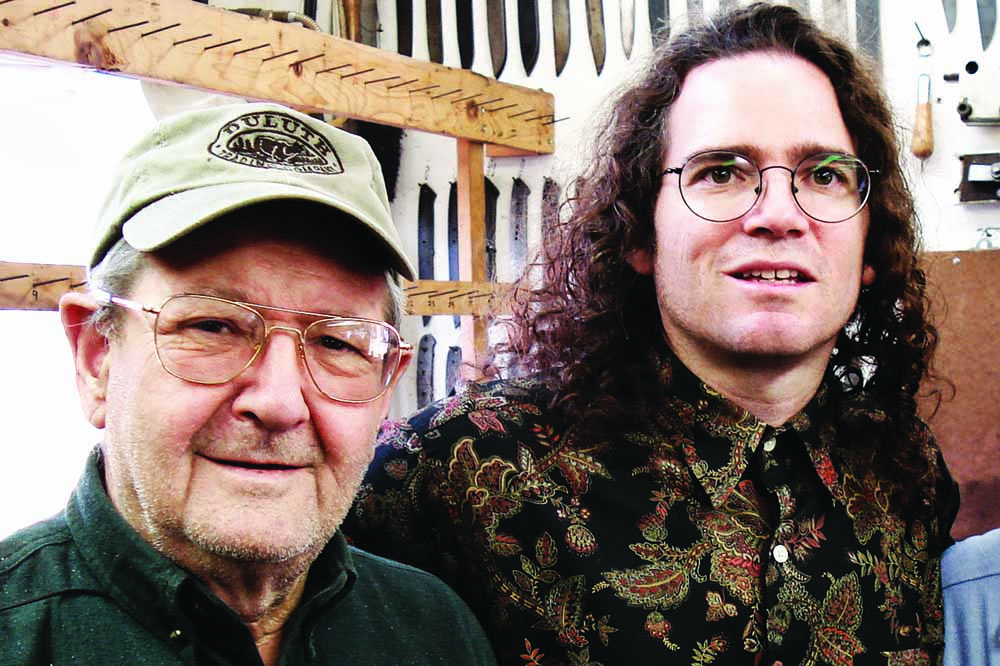

Christensen got his start making stock removal knives after a career as a horticulturist. He learned to forge while working with ABS master smith Ed Caffrey and visited with knifemaker Rick Eaton and ABS master smiths Shane Taylor and Wade Colter. Jon also makes San Francisco folding knives and enjoys swordmaking. Plans for the future include more period knife examples.

Kimbll Style

ABS master smith Josh Smith owes his little league baseball coach, ABS master smith Rick Dunkerley, credit with getting him started making knives about 30 years ago. From the beginning, Josh has appreciated the thought process and craftsmanship of custom makers from a bygone era.

“There’s something special about reproducing something that was built nearly 200 years ago,” he reasoned. “It’s easy to get lost in your thoughts while working on these knives, wondering what the makers were thinking about at the time. Was the knife going into battle? Was a rich man just wanting something unique? Was the maker just trying to be different and impress people? Were function and effectiveness of use the only factors that mattered? It’s really cool to think about.”

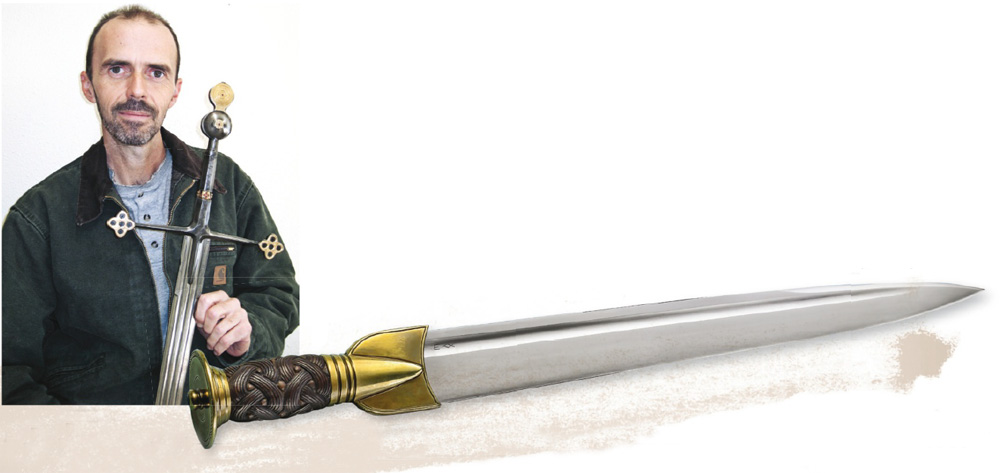

Josh has found the opportunity to consider historical context with a dagger in the distinctive dog-bone handle, recalling the mid-1800s when a gentleman named Loring Kimball of Vicksburg, Mississippi, owned several similar original pieces that were probably made by at least two different knifemakers in the New Orleans area. Knives in what many refer to as the Kimball style have been reproduced by a number of modern makers, mostly bladesmiths.

“The distinctive characteristic of the dog bone is clearly the shape of the handle,” Smith said, “but to me it’s more than that. The large domed pins and the flat facets on the handle provide such a neat look. One of the original Kimball daggers from the 1830s had silver wrapped around the butt of the handle and a small, thin silver guard. I never pretend to exactly reproduce these knives. I always put my own spin on the knife, trying to bring some of my style into it.”

Smith’s dog-bone dagger is fashioned from his own ladder pattern “W’s” damascus blade, African blackwood handle and 18k-gold pins and liners. The 9.5-inch blade is forged from 1080 carbon and 15N20 nickel-alloy steels, while a gold collar stretches over the back of the blade and bears the engraved name of the maker. Overall length: 14.25 inches.

“This particular knife was heavily influenced by Tim Hancock,” Josh said. “I feel Tim, Harvey Dean and James Batson are the three men who led the way in bringing these knives back to prominence, and Tim had the most influence on my construction of these knives. I love period knives and definitely plan on doing more. There are so many incredible weapons from the past that would be fun to recreate.”

*While a number of top industry authorities attribute such original 19th-century pieces as the Carrigan Knife, Bowie No. 1 and others to Black, no knives with Black’s mark are known to exist.