Top makers explain how they collaborate with knife companies.

The old cliché of the win-win holds a real grain of truth. Any successful partnership must be mutually beneficial, and in the knife industry the phenomenon of the collaboration has come to exemplify the upside of working together.

Years ago, a veteran custom knifemaker described his relationship with a major manufacturer as serving as the company’s research and development department. Such a description is accurate in that the manufacturer often relies on the custom maker for new design inspiration, from good looks to materials and mechanics. The collaboration has emerged in the last 35 years or so as an outstanding means of bringing innovation to the public and putting first-rate knives in the hands of the mass market.

The ins and outs, nuts and bolts, and give and take of the collaboration process raise questions for makers interested in striking deals of their own. A few comments from makers who have achieved great success on the collaboration frontier offer helpful insights.

“It goes both ways,” observed BLADE Magazine Cutlery Hall-of-Fame® member Bob Terzuola, who indicated he completed his firstfactory collaboration with fellow Cutlery Hall-of-Famer Sal Glesser and the design team at Spyderco in 1989. “You can go to the company or the company can come to you depending on your notoriety. If you are just starting out, you probably have to go to the company.”

On the business side of the ledger, Suzi Terzuola takes the lead and has demonstrated proficiency in making the deal work for everyone involved. Her flair for negotiation and finding the right blend of maker-manufacturer cooperation has been demonstrated through the years as Bob has worked not only with Spyderco but also the old Camillus, Boker, Fox, Pro-Tech, Tactile Knife Co. and others.

“I was raised by parents with their own successful businesses,” Suzi observed, “and I saw Bob receiving passive income from Spyderco and Camillus, and of course passive income is how you survive after having only so many years to make knives. I began looking at the knife designs Bob had and tried to match the design to the company. Bob has patents lining the walls, and when he lends his name to a knife he should receive a signing bonus and a bonus against the royalties.”

In return for his design skill and the use of his name in promotions, Bob has certainly established himself as a leader among successful custom collaborators. His contribution to a company’s success has enhanced his reputation of excellence across the industry, while Suzi has forged a business posture that results in security for the future.

Knife Collaboration Contracts

The contract is the key component of a collaborative deal, and depending on the circumstances everything is negotiable. Although early agreements made among friends were sometimes done on a handshake, it has become a “best practice” to hammer out the terms of the collaboration on paper, invest in an attorney’s review, and formally memorialize the discussions. Standard royalties run roughly 5 percent of the price at which the company sells the knife.

The Terzuolas include a period of time in which the company is allowed to produce the knife; the period may be extended at maturity with the agreement of both parties. Further, there may be a requirement that the company produces a certain number of knives in a given time period, also renewable. Restrictions on wholesale pricing or discounts that affect royalties may also be negotiated.

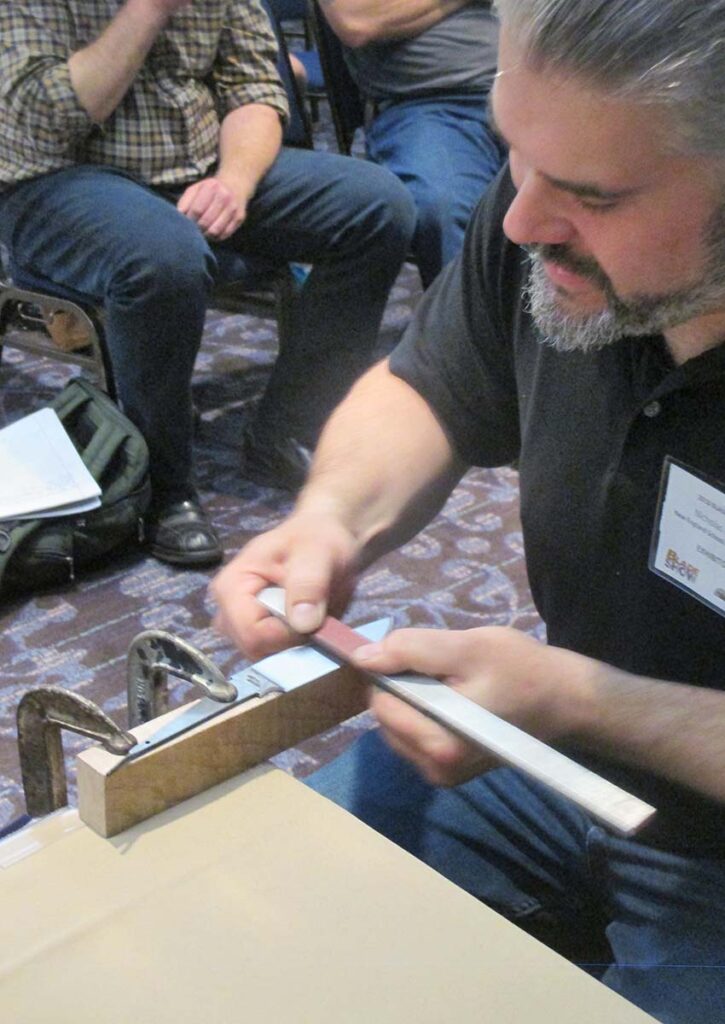

For those considering a foray into collaborations, Bob and Suzi offer some advice: “If you’re a new maker, you shouldn’t just walk up to [the company’s] booth at a show. Make an appointment to see them because they are at the show to deal with customers. Approach a company with one or more finished designs. They want a package presented to them, a prototype or existing model, something they can hold in their hands, and in the case of a prototype it’s good to have as many innovations and design creations as you can—anything that will set the knife apart from other potential deals out there.”

Suzi added that a higher profile in the industry can drive success.

“We are the R&D for a knife company,” she noted, “and when you approach them for a collaboration your social media resumé is very important.”

Making custom knives since 1994, Darriel Caston has concluded collaborations with numerous companies, including CRKT, Spyderco, Boker, V Nives, Kansept Knives and more.

“I’m prolific when it comes to designs,” he affirmed. “There are probably about 300 that I will never get to making. I’m an engineer by trade and my 3D drawings are almost ready for production, and that helps with the deals. They ask for STEP files [standardized 3D model data files for CAD and 3D printing] that can go right into machining. Sometimes we work with a prototype, and sometimes we work with a knife that I have been doing for quite a while.”

According to Darriel, one significant element of the collaboration is the retention of the rights to the design.

“You never want to give up your design,” he warned. “I would license the design to the company usually up to four or five years, and the average is three years. After that, you can discuss if you want to continue if the relationship has been good for both parties. License the design and never sell it. If a company buys the design, then they own it forever. If it became their best seller, I could never make the knife again, and I would have to stay away from anything that looks like it.”

For Caston, every deal starts with a friendly conversation. As progress is made, attorneys draw up the contract. He sees the process as straightforward, whether dealing with an American manufacturer or a company headquartered in a foreign country.

“I find the knife community for the most part to be very honorable,” he commented. “I haven’t run into any bad juju. When you want to do a collaboration, I tell people they need to have a name and a track record of good designs with people following them on social media and stuff.”

Since his first collaboration—with Spyderco in 2015—Darriel can speak with confidence regarding the potential for success.

“It would be rare for someone to take a design to a company without a history or a footprint there. They look for your story,” he noted. “Anybody who wants to do a collaboration must put footprints in the sand, get their work out there and show a story. Then it becomes easier.”

Getting A Collab Off The Ground

Custom maker/U.S. Marine Corps veteran Les George found early collaboration success at the SHOT Show some years back. He approached Pro-Tech a decade ago, and the association has continued since then.

“I had just finished my first batch of VECP [Value Engineering Change Proposal] mid-tech knives,” he remembered, “and I thought it would be cool to see Pro-Tech make the knife in an automatic. So, I did the CAD work to change the knife to an automatic and walked up to their booth at the SHOT Show. I asked to speak to the owner, and Dave Wattenberg came over and shook my hand. I drew a big breath and told him, ‘My name is Les George and I am a knifemaker and I have a design I think would be a great knife for you to make as an auto and I already have the CAD done would you like to see it?’ I said that all as one sentence in one breath!”

Still, a pragmatic view of the collaboration landscape demands preparation and planning. A so-called “cold call” may not meet with success.

“It depends on the company whether a direct approach will work or not,” George conceded. “Don’t walk up to a company at the BLADE Show and tell them you’re a hot maker and they should pay you to make one of your designs. Instead, walk up, introduce yourself, and show them with CAD pictures, a 3D printed model, or a real knife, and tell them why you think it would be awesome to work with them on a production project.”

Les sees the components of a particular collaboration deal varying. Of course, some of the structure depends on the negotiating skills of the parties. Commonly, the compensation may revolve around a percentage of dealer or distributor pricing on each unit, and particular deals may extend as long as each party is pleased with the progress.

“Collaborations should run as long as they are profitable,” Les remarked. “Companies don’t generally kill a successful project unless there is a capacity constraint issue or something else outside hindering it. Both parties can end the deal at any time with some allowances for production to finish with the things they have in progress already. Every contract I have ever seen gives one company the rights to exclusively make a particular model. My contracts have a provision that I can make as many customs of my models as I want. In the end, it would be counterproductive to license the same model to multiple companies. The maker would be competing with himself at that point, and it’s not helping the companies.”

Priming The Pump

Award-winning maker Lucas Burnley appreciates the help of friends in establishing a firm footing for collaboration.

“In general, I’m a big fan of pulling on my network,” he said. “If you have someone you can reach out to for an introduction, that’s always a strong move. If you don’t have someone to make an introduction, you might be able to ask around and at least figure out who you need to talk to. Regardless of how you get your foot in the door, I highly recommend going to a knife show and trying to set up a meeting in person.

“A design is only one part of a collaboration,” he continued, “so bring your ‘A’ game and think about what other value you can provide for the company. I was introduced to Boker by Jens Anso and Jesper Voxnaes, and Ken Onion put in a good word for me with Columbia River Knife & Tool. I’ll be forever grateful for those introductions and the relationships behind them. I’ve been able to pay it forward a few times, and hopefully I’ll be able to do it many more times in the years to come.”

In Burnley’s experience, contracts provide compensation most often in the form of monthly or quarterly royalties based on a percentage of sales. One-time lump sum payments are also seen; however, the income generated depends on the goals of the two parties involved.

“I want my designs to run until my grandkids are old enough to thank me for my good decisions,” he laughed. “If a model is selling, I want it to keep selling. On the flip side, I will routinely ask what models we can kill if they aren’t pulling their weight.

“One caveat here is that if a design is still in production, I want to get paid for it,” he concluded. “Some companies will offer a contract for a set period of time but have the option of continuing to produce the model. I view this as somewhat akin to a one-time payout. If it works for you great; just make sure you are paying attention.”

George specifically limits the number of companies he works with in order to give the relationships the priority he believes they deserve. Consistency, he says, is huge. Real, solid collaborations are not “get-rich-quick schemes.” He remembers getting his first collaboration check in 2014 totaling a whopping $6.

Times change—and checks change with good business practices, commitment, follow through, and most of all a process from contract to design and product that proves profitable for everyone.