Know how the pros keep their knives and sheaths in tip-top working order.

Tricks of the trade, the go-to products, and the techniques that stand the test of time and use are beneficial for those of us who put our knives to work around the house, at the office, on the farm and in the field. Keeping the knife in top-notch working order eliminates frustration and failure when it’s time to get a job done.

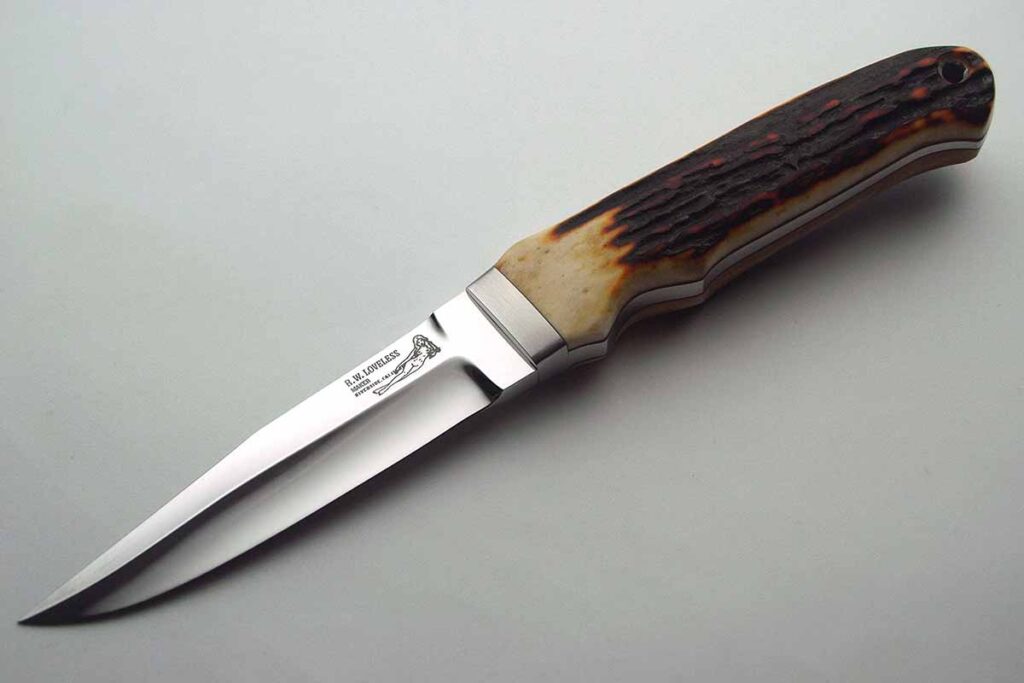

Fighting Corrosion

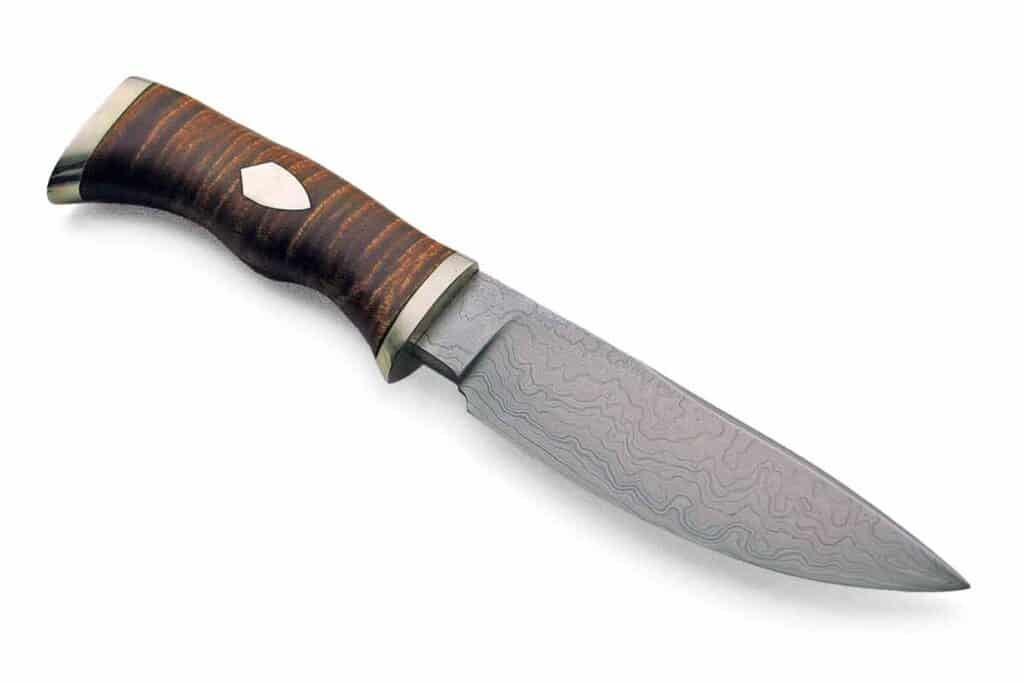

Fighting the battle against rust is ongoing with carbon steel. Long-time custom knifemaker Bob Dozier said, “Wipe the blade off. I’ve carried a folder since 2014 and use it every day. A lot of it depends on how the maker heat treats the blade.

“I established my reputation with D2 steel,” Bob continued, “and there are a lot of steels that hold an edge a little better, some that are more corrosion resistant, and some that are tougher, but just keep it clean and it won’t rust—the chrome on the outside is a few atoms thick. D2 is bright at first but will take a little bit of a dull look. Don’t worry about that in a using knife.”

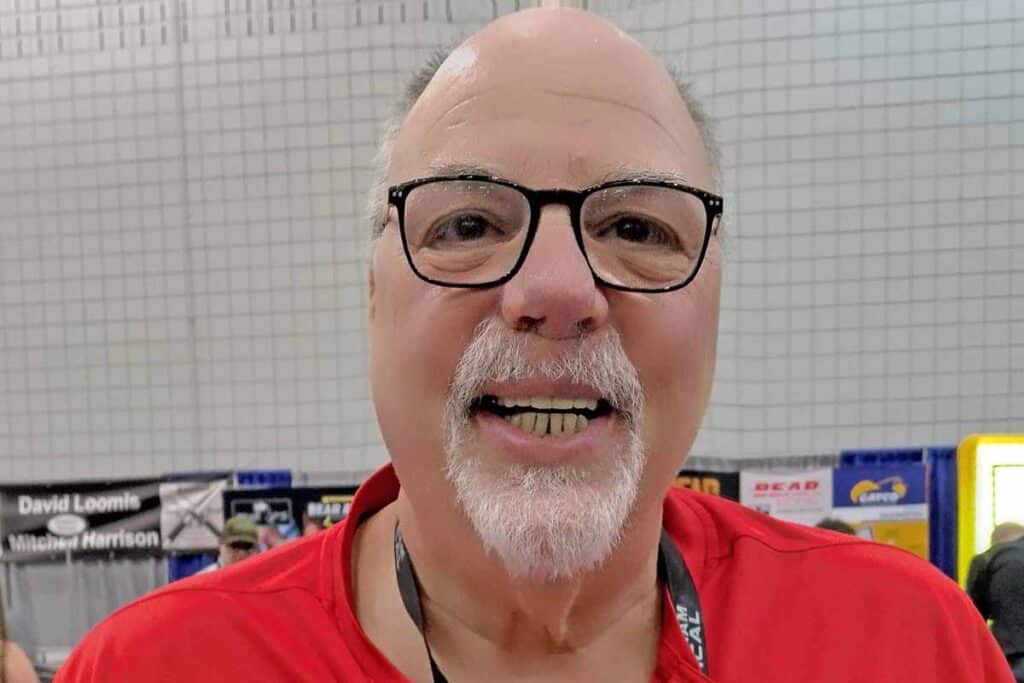

BLADE Magazine Cutlery Hall-of-Fame® member Bill Harsey says oil the blade as well as part of routine knife maintenance.

“The one oil I use on folding knives is Kano Aerokroil,” he noted. “It’s a true oil and does not evaporate. Clean the knife and put it away dry after using it.”

If that troublesome tinge of rust does show up, Bill Claussen of Northwest Knives and Collectibles reaches for a polishing cloth and paste. In more extreme situations, steel wool or wet/dry sandpaper can get the job done.

“We use Case’s Paste Metal Polish or Flitz Polish as a metal paste and corrosion protectant,” he remarked.

Other techniques and favorite products to prevent or remove rust include the careful use of steel wool when necessary, a preventive application of 3-in-One Multi-Purpose Oil, the combination of oil and Renaissance Wax, Wicked Wax, and even regrinding and repolishing in an extreme situation when pitting is present.

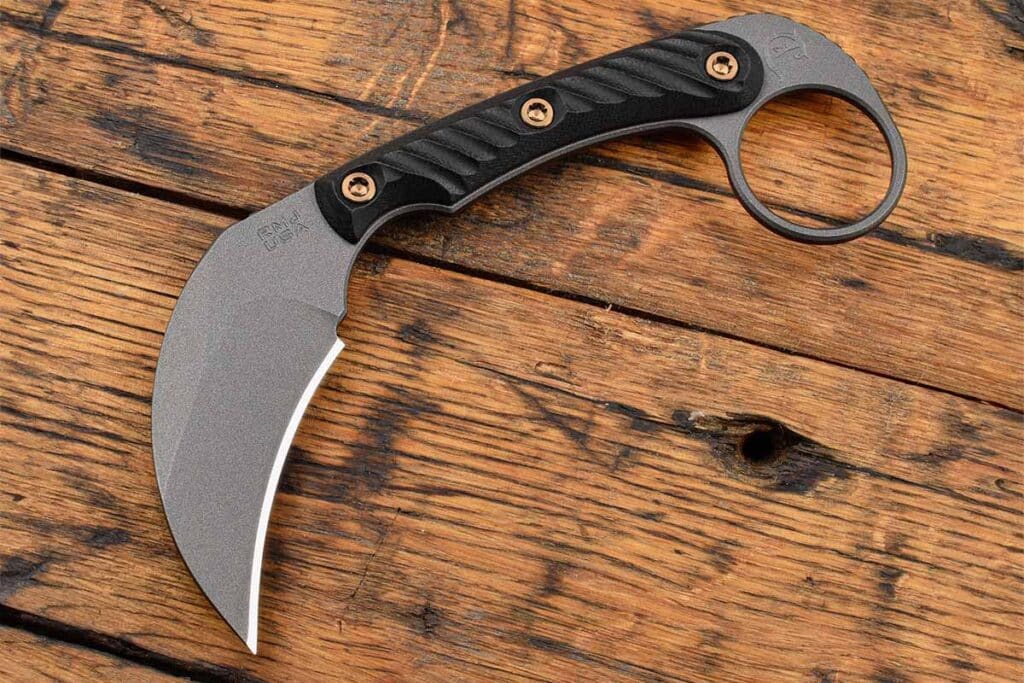

“I like 3M pads to remove rust on our malnourished edges out in the bush,” related bushcraft pro/knife designer Joe Flowers, “along with rust erasers for those fine knives some clients bring out with them. Ballistol makes good stuff including multipurpose oil in small single use packages that can be handy during hunting season when I also have firearms.”

Screw And Bolts

Loosening a bolt or screw that has frozen is a frustrating situation, but there are a few products that ease the task and a trick or two to employ when necessary. Cutlery Hall-of-Famer Dan Delavan of Plaza Cutlery offered, “I use WD-40 and chase it with an oil if needed, such as Formula 23 knife oil.”

Cutlery Hall-of-Famer Steve Schwarzer added a proviso.

“Normally that would mean using a penetrating oil, but the other thing you can do is set up a carbide drill fixture a little smaller than the diameter of the stuck screw and drill out the screw,” he wrote. “You can also use an induction heater and stick the knife in there to help spit the screw out. Heat will break down epoxy but don’t get it over 300 degrees. Unless you’re skilled I wouldn’t advise it, but it beats pressing the handle off and can save the material if you’re careful.”

For loosening blades or screws that have seized up, other noteworthy products include AutoBright, Kroil Penetrant, CRC Electrical Silicone lubricant and Marble Oil. “The Marble Oil is [inexpensive],” ABS master smith Harvey Dean observed.

“It works well to get something unfrozen and I used it on a pocketknife a while back. Anyway, if you put a drop of oil on the blade or joint once in a while it sure does help.”

Harsey has a great tip for loosening troublesome screws or bolts.

“I go right to the Kano Aerokroil to start the rehabilitation,” he commented. “A lot of people take folders apart when they don’t have to do that. Get a box of cotton swabs with paper stems and hammer their cotton heads flat to fit inside the small spaces of a folding knife. You can do that to oil the knife up or to clear gunk out of it. The cotton swab will show you what you’ve got without disassembly.”

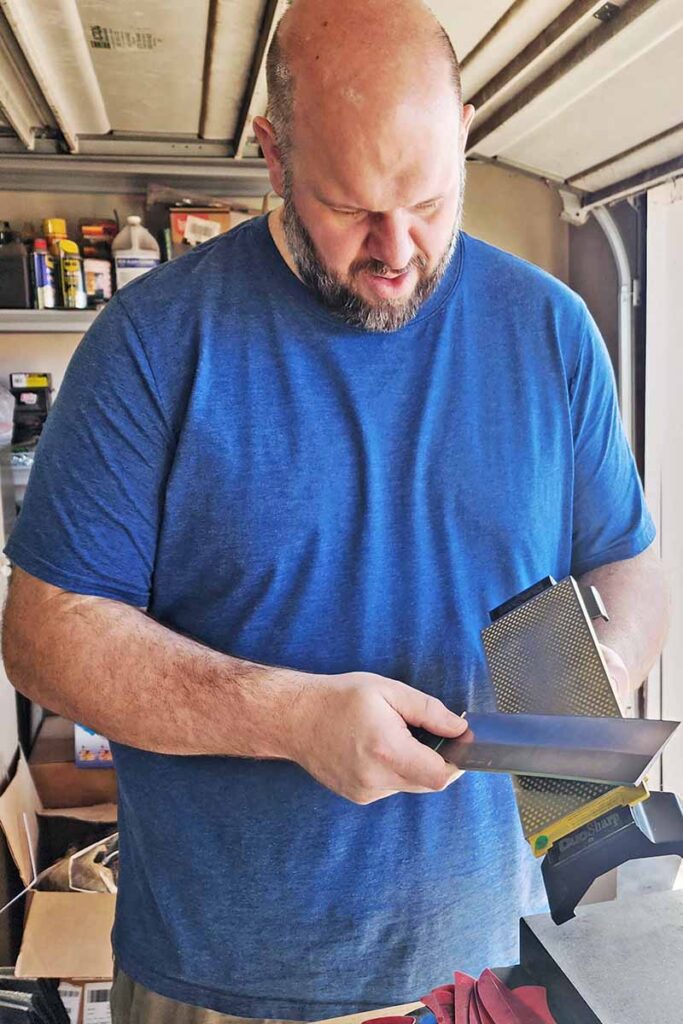

Edge Maintenance

Keeping a working edge sharp is a never-ending knife maintenance job, and Harsey has spent years making knives, designing them for many prominent companies, and putting them to work in the field.

“I like to use an EZE-Lap stick diamond sharpener or honing stone with a plastic handle,” he advised. “Hold the knife still in one hand and scrub on the blade with a good angle on the sharpening bevel, then turn it over and do the other side. The result is a remarkable working edge that will do in the field.”

Harsey also likes the Norton fine India sharpening stone.

“When we go out in the field, I have never traveled without one,” he commented. “I use a rubber drawer liner mat that I can unroll and put the stone on so it won’t slide around on a truck tailgate. That becomes my workbench, and I’m the sharpener for half a dozen guys out there. At other times, I might finish with some stropping with a little WD-40 and cream buffing compound in the leather.”

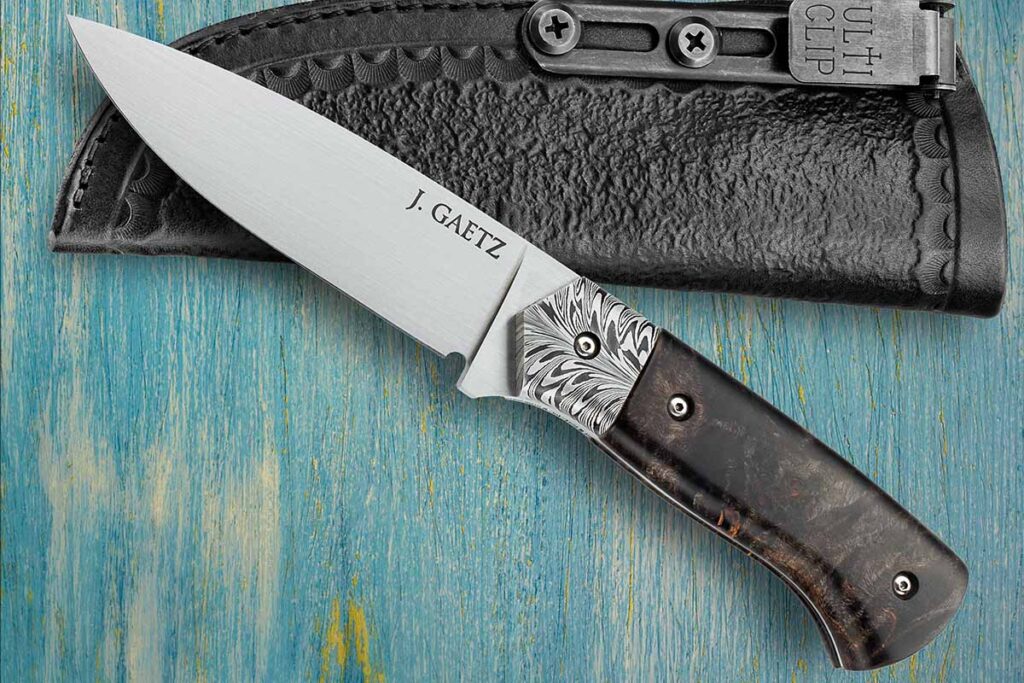

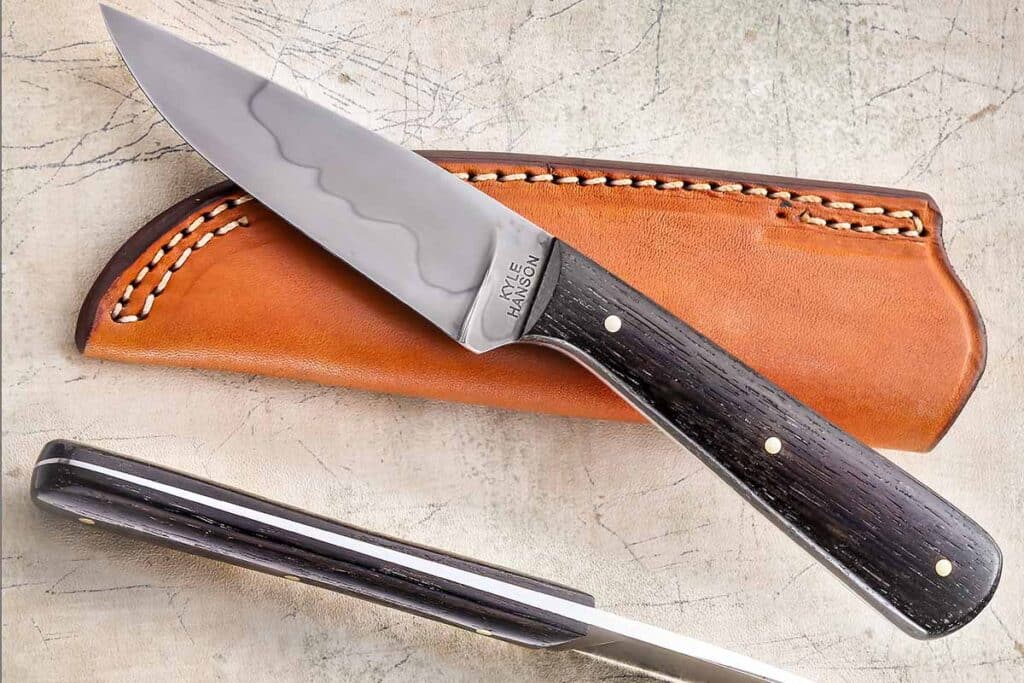

Sheath Maintenance

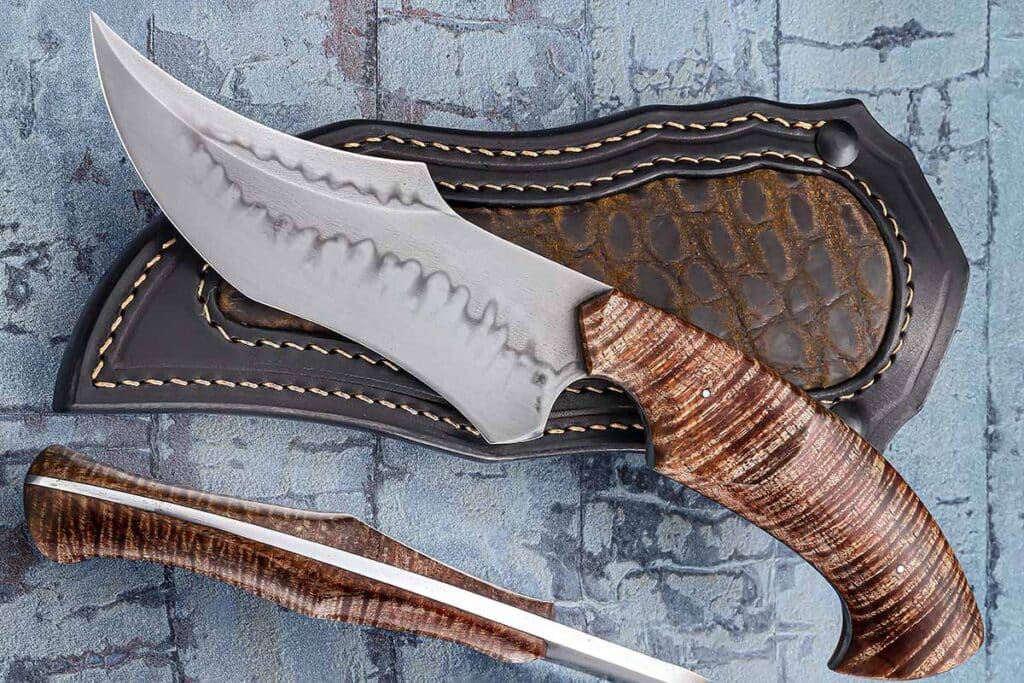

Schwarzer is a big fan of hot wax in both knives and sheaths.

“I hot wax everything,” he said. “I have posted it online a bunch. Paraffin wax in a turkey roaster is best, and when I make my knives I put them all in there and then wipe off the excess. It also turns any leather sheath into a form of Kydex. Put it in there for a couple of minutes at 300 degrees, wipe off the excess and form the sheath with your hand. It won’t scratch your blade like Kydex will.”

Dozier has a simple approach to sheath maintenance.

“Wipe off the sheath,” he noted, “and then put a tiny little bit of WD-40 on a cloth and wipe it down. You can also use neatsfoot oil. A little bit on a cloth will keep the dirt off. You can spray a little bit of WD-40 into a bottle cap and leave it on a shelf for four to five months and you have nothing more than cosmoline or grease that works for protection, too.”

Dean likes to protect his sheaths as well.

“I always put some kind of coating with wax or a spray aerosol finish on them,” he remarked. “I don’t recommend storing a knife in the sheath. I use American tanned leather, but some of the other leathers out there use salt in the tanning process, and that can cause problems with a blade.”

Harsey follows steps to make a leather sheath “knife friendly” so that one does no harm to the other. “When I hand build a leather sheath, the leather is always 10-ounce and tanned in vegetable oil,” he said. “It’s a straight, clean piece of heavy leather, and the preservative is either neatsfoot oil or a combination of one-third neatsfoot oil, one-third bees wax and one-third paraffin. That’s heated to 150 degrees, and I’m darn sure not to go any hotter or you could wreck your sheath. I preheat the mixture, paint some on, and put it back in the oven and repeat several times. Then wipe it off and let it dry. If I’m in the field and it takes more than just wiping the sheath off, something has gone wrong.”

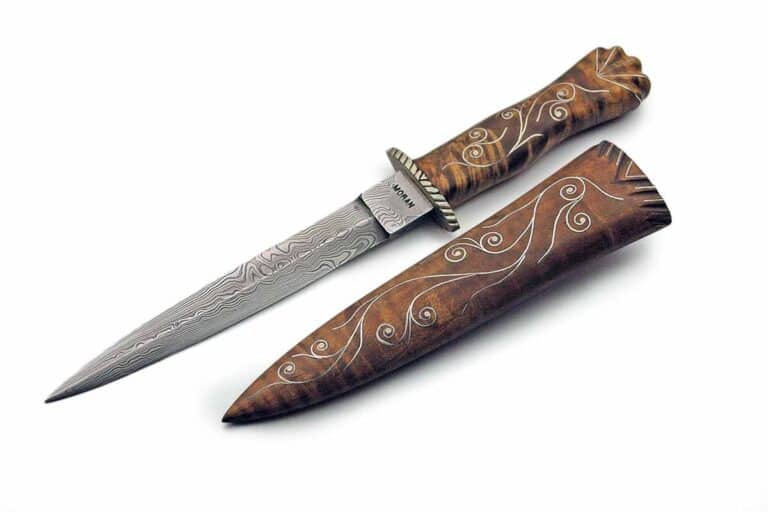

Climate Control

Natural handle materials are always in need of some protection. Climate can cause expansion and contraction, while extreme heat and cold are detrimental, too.

“If it’s a wood handle, keep it dry and clean,” Dozier offered. “Don’t throw it in a bucket of water. Ivory needs to be dry too, and a little Navy oil or mineral oil or even a little oil off the end of your nose will help keep it from drying out too much.”

Dean adds a little advice for the owner/user who wants to maximize the longevity of their knives.

“People a lot of times just don’t take care of their knives,” he said. “I got a good damascus hunting knife back from a guy who said he had forgotten about it. He left it on the floor of his Jeep and never cleaned it. The thing was basically ruined. I made him a new knife, charged him, of course, and kept that other one myself. I had to regrind and rework it, but it wasn’t the knife it used to be.

“The main thing,” Harvey concluded, “is to take a little time with them.

Wash a knife off in hot water, the blade anyway, and don’t put them in the dishwasher! A lot of times, people take knives on hunting trips and leave them in the sheath or on the dashboard of their truck all day with the sun shining on them. Don’t do that! It’s bad. Natural handles can shrink and crack, and a windshield is like a magnifying glass.”

Try these tips. Test these products. And see for yourself how the pros actually make the best of owning and maintaining a knife in tip-top condition through the years.

For the knife and sheath maintenance items in the story, contact any of the knife suppliers who advertise in BLADE®. If that doesn’t work, enter the name of each applicable product in your internet search engine—all or almost all are offered by a wide variety of outlets.

More On Maintenance:

- Pros’ Secrets To Sharpening Knives

- Best Sharpening Stones To Keep Your Edge

- Knife Sharpening Angle: What’s Best

- 5 Myths About Knife Sharpening