Four knife industry pros share the secrets of how they keep their edge when sharpening.

A knife is made to perform its function as a tool, and job number one is to cut.

It follows that the development and maintenance of the edge is the most important aspect of knife ownership and use. When users are in the shop, around the house, at the office or in the field, keeping the edge in top form and working order makes the task at hand easier and often saves time and effort.

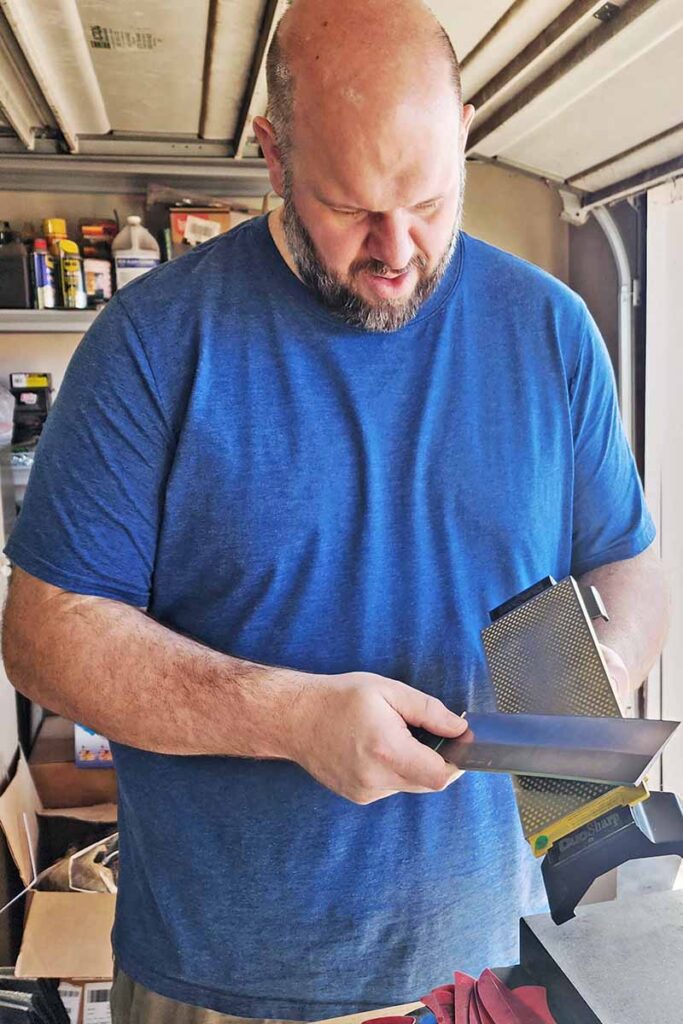

Custom Knifemaker: Chris Berry

A custom knifemaker for 15 years, Chris Berry has made a name for himself in heavy-use choppers with blades of high-wear-resistant steel.

“When I finish a knife and get ready to sharpen it, I break the edges on the grinder to start the process and then work freehand after that,” he explained. “I’ll start with an extra-coarse DMT diamond stone and then go from extra coarse black to red medium and then green extra fine.”

In the field Berry carries a Spyderco cubic boron nitride (CBN) sharpening stone along with a Spyderco Double Stuff pocket stone.

“It has medium and fine ceramic for the edge,” Berry continued, “and then I’ll have some piece of leather to strop the blade and remove the burr.”

Chris knows it’s time to touch up an edge when it starts to drag through the cut.

“A blade is dull when it won’t cut printer paper,” he said, “so I’ll sharpen it before it reaches that point. I’m not obsessively sharpening a knife blade, but I’m just hitting the medium edge of the Double Stuff and going to the strop to bring back that popping edge. I usually only go back to the grinder if the edge is damaged, but, if the blade is really dull, starting with the extra coarse diamond and going through the grits will make it like a new knife.”

As Berry noted, the burr is the little, fine piece of steel that rolls up to the edge of the blade and is rough on one side and smooth on the other.

“If the burr isn’t gone after sharpening [the edge is] not sharp,” he advised. “In my opinion, it is the key to whether a knife is sharp or not. I tell people on social media that sharpening a blade is broken down to apexing the edge to raise the burr, refining the edge with progressively finer grits, and then removing the burr by stropping. If you progress through the grits and have the burr removed, you should be able to cut newsprint, phone book paper and even paper towels. That is as sharp as you are going to get.”

Knob Creek Forge: James Gibson

James Gibson of Knob Creek Forge designs knives for ESEE and teaches classes on bushcraft and survival.

“I like a full flat grind with a convex edge,” he remarked. “They say the convex edge is the best, and when I have an extremely dull blade I use these little diamond files and then a ceramic rod or stone that will stand the edge up.”

An ABS journeyman smith, Gibson cautioned, “A dull knife will hurt you quicker than a sharp knife because you tend to lose control when you apply more pressure to get a job done. Most of the time I will sharpen a knife at the end of the day, but if it is not performing I will touch it up right then and there. If you ever watch a carver, they will carve for 15 minutes or so and then strop the blade to bring the edge back right quick. After a few days of stropping, they will have to do a bit of sharpening.”

Gibson sometimes uses a marker to spot the blade about a quarter inch up from the edge and then “floats” the edge up and down the diamond sharpener. He then moves to the leather strop and notes that if a compound has been used to keep the leather in shape the process will turn the leather black.

“That means you are pulling steel off the edge,” he commented, “and where the two polished edges meet that will give you the sharpest blade you can get.”

Safety is a constant concern for Gibson and he stresses this aspect of knife use in his classes.

“We train people on the knife, and one of the first things we tell them is never to cut toward yourself. Keep everything out in front of you, or use a bench, log or stump so that everything is out of the way.”

CRKT: Russ Kommer

As a knife designer for Columbia River Knife & Tool (CRKT) and a hunting guide, Russ Kommer keeps blades sharp on a regular basis.

“When I finish up a custom knife, I run the blade on a brand new 400 grit slack belt with a real slight radius,” he remarked. “Then I will take it over a used 400 grit belt so that when the edge is curled and there is a little white line, I can use a leather strop or a 10-inch wheel and break off the burrs.”

Kommer carries a diamond sharpener in the field to touch up an edge.

“That will stand that line back up and remove some steel to get the edge back to infinity,” he said. “The only way to get a blade sharp is to remove enough steel. In the field you can use a leather strop or even the leather heel of your boot or something to help. When guiding, I have done two moose and a caribou in one day, and working on big animals is a big job. Sometimes I will carry two knives and touch both up to be ready for the next week, and I carry a pocketknife for cutting rope or other camp chores. It’s not good to use your hunting knife to cut burlap and dull it up on something like that.”

Testing for sharpness is a varied exercise, and Russ likes the simple standard.

“Guys like to shave their arms and that is all cool and dandy,” he smiled. “I just rake it across the back of my head, and when I feel it grab that hair I know the blade is sharp. There is also the fingernail task—if you feel the blade grab right there on the fingernail, then it is sharp. If you have practiced sharpening a blade enough, then you know quickly just how sharp a knife blade is.”

Condor Tool & Knife: Joe Flowers

As a knife designer for Condor Tool & Knife, Joe Flowers has sharpened thousands of blades through the years. The sharpening process is dependent largely on the work at hand.

“It can vary between jobs,” he explained. “I just have a 2×42 grinder that I do edge modification on—with every belt imaginable—but by far I use the leather belt the most because I am always using the blades and getting a fast strop. Most of the time, I try and use my field sharpeners and also complement them with the finer stones like my King stones or Spyderco ceramics.”

When Flowers ventures into the field, he is prepared for the occasional sharpening task.

“I really like EZE-Lap’s double sharpener,” he advised. “The files really bite down on carbon steel, and the ceramic on the other side keeps a finer edge. I’ve even used the sheath as a strop. That and the Spyderco Double Stuff are my two favorite compact sharpeners, although Work Sharp’s setup is great, too.”

When in the field, Flowers likes to settle down before taking on the sharpening of his knives.

“Normally, in camp situations, unless I’m working hours on a game animal or on a bushcraft project, I leave my sharpening to nighttime around the campfire. I also have my field sharpeners around my desk at work to use to understand how they work on different steels more. I like using EZE-Lap and diamond stones with harder-use bushcraft [carbon] steels like 1095. It can get an edge fast and you can go about your day.

“For machetes,” Joe continued, “I stick with what the locals use, and that’s a file. Generally, I’m working with softer steels for machetes so a triangular single cut bastard or double cut bastard file about 6 inches long is a nice addition to my sheath. I’m finding better results in super steels on diamond stones until I move into these new crazy preloaded diamond powder strops. Those look incredible to try.”

When sharpening a dull blade, Flowers is known to use 60- to 80-grit belts to re-form edges when large chunks have been taken out of a machete, for example. He maintains that it can take the steel off the blade fast but there must be a bucket of water or a spray bottle handy to keep the grinding surface cool.

Bringing a knife back from dead dull involves a proven process.

“At home I would reprofile gently on a 1×30 Harbor Freight special I’ve had from the old days,” Joe commented. “Depending on the steel and use and the comfort of the hardness, I’ve reprofiled knives from dead dull with homemade sandpaper and mouse pad backing and keep heavier grits there as well. You can definitely over sharpen a knife by stropping so much you roll the edge. In the technique, you need to be able to tell when you have just the right amount of pressure.”

Sometimes the type of sharpening medium used depends on the blade steel, the style of blade and the common utility of the knife.

“On many higher-end-steel kitchen knives, I stick with King stones because they are tried and true,” Joe related. “However, I like many different media for various steels, going for the extra-fine edges or a strop loaded with compounds for the final edge. For things like serrations, I use thinner round diamond rods for getting the radius, but I don’t deal with them much. I really like the flattest surface possible when I sharpen Scandi as it helps keep the angle straight.”

Retaining a sharp edge makes life easier wherever and whenever a knife is needed. A few minutes to shape up a blade is always time well spent.

More Sharpening Articles:- Knife Sharpening: What’s the Best Angle?

- 5 Myths About Knife Sharpening

- 5 Leading Sharpening Rods

- 4 Steps to Perfect Freehand Sharpening

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

BLADE’s annual Knife Guide Issue features the newest knives and sharpeners, plus knife and axe reviews, knife sheaths, kit knives and a Knife Industry Directory.Get your FREE digital PDF instant download of the annual Knife Guide. No, really! We will email it to you right now when you subscribe to the BLADE email newsletter.