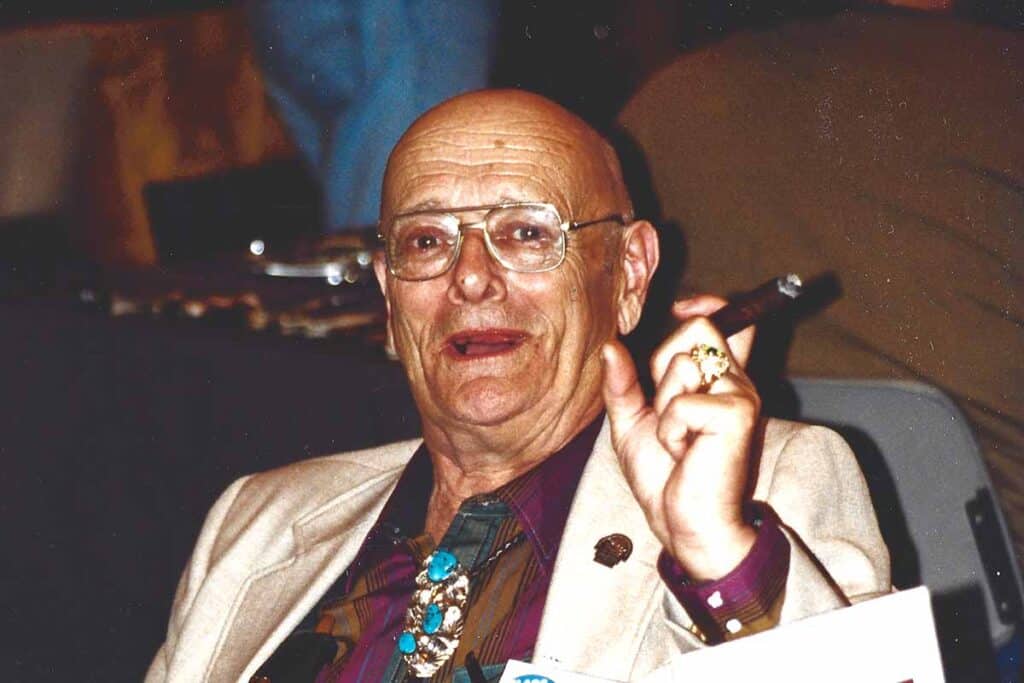

We talk with those who know Bill Moran best to determine how many damascus blades the godfather of the craft forged.

BLADE Magazine Cutlery Hall-of-Fame® member Bill Moran is and will forever be remembered as the father of modern damascus steel. He and a few early devotees popularized damascus during an era when the art of bladesmithing was an endangered species in the realm of the artisan.

It was Moran who shocked the custom knife world in 1973 when he brought eight knives to The Knifemakers’ Guild Show in Kansas City, Missouri. Those historic eight sported blades of Moran’s damascus steel and they created a sensation. Cutlery Hall-of-Famer, longtime journalist and friend of Moran’s, and a respected member of the knife community, B. R. Hughes remembered how the event electrified those who attended.

“When my wife [Carolyn] and I drove up to the Muehlebach Hotel in Kansas City, a friend of mine came out and said, ‘You gotta get in there and see the damascus knives Moran has on his table.’ Those knives were the talk of the show. Bill also had mimeographed sheets that explained what damascus steel was and how it was made. He gave those sheets away to anyone who desired one.”

Three years later, Hughes joined Moran and bladesmiths Bill Bagwell and Don Hastings as the quartet that founded the American Bladesmith Society (ABS). When the ABS was founded in 1976, bladesmithing was on life support, and probably fewer than a dozen smiths were forging knives. Today, the Society includes more than 2,000 members and the future of the craft has been secured. Meanwhile, Moran deserves the credit as the catalyst for modern bladesmithing.

How Many Damascus Knives Did Moran Make?

While there is no question that Moran and other dedicated disciples of the forged blade brought damascus and the ring of the hammer back to life in the early-to-mid-1970s, there is some conjecture as to just how many such knives the great Moran forged and completed himself. The thought of how many Moran damascus knives were made and exist today is tantalizing, and, of course, what’s a great legend without a bit of mystery and conjecture? Exploring Moran’s body of work and the damascus element within provides some insight into the man, the legend who padded about on the creaky floor of his Maryland shop, sometimes chewing tobacco, but rarely alone when his doors were open as crowds came to see the wizard work.

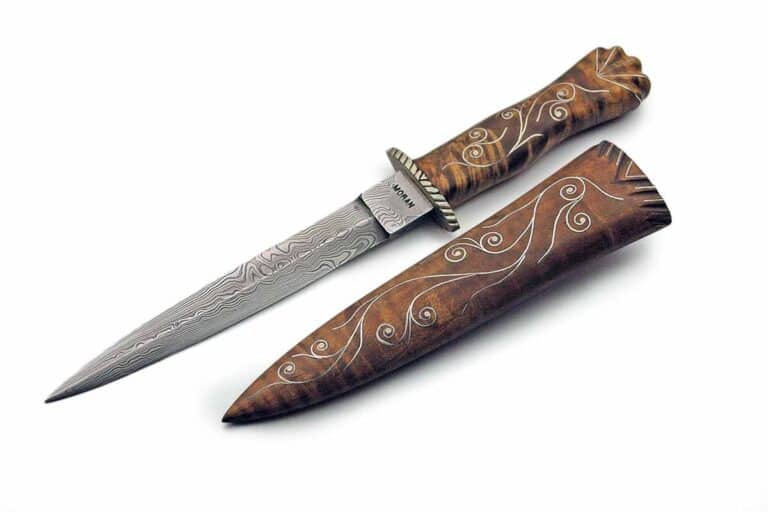

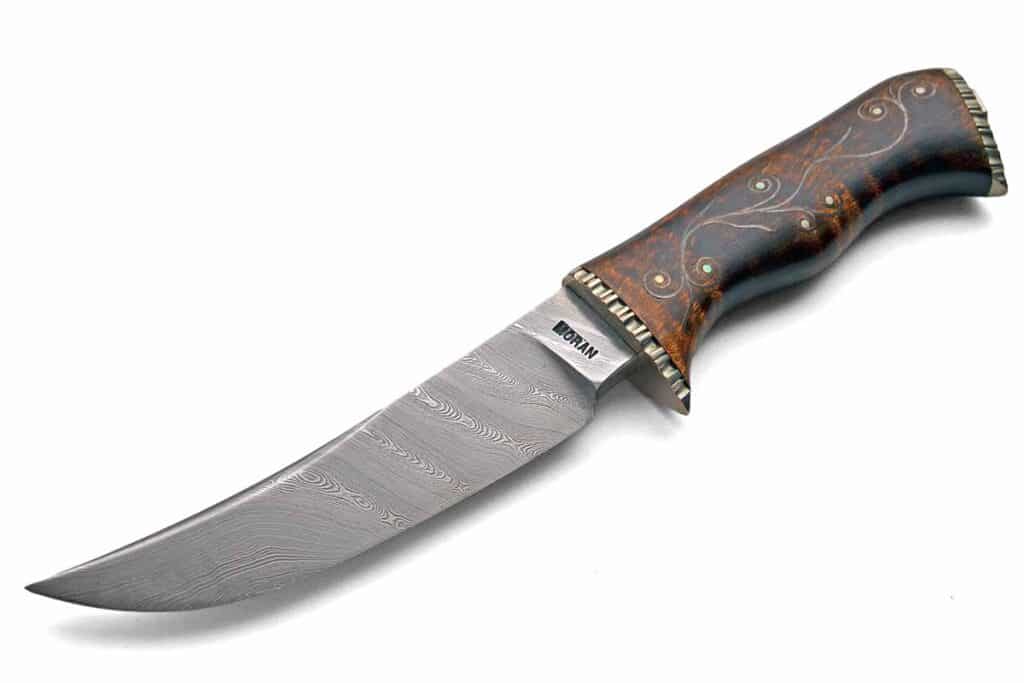

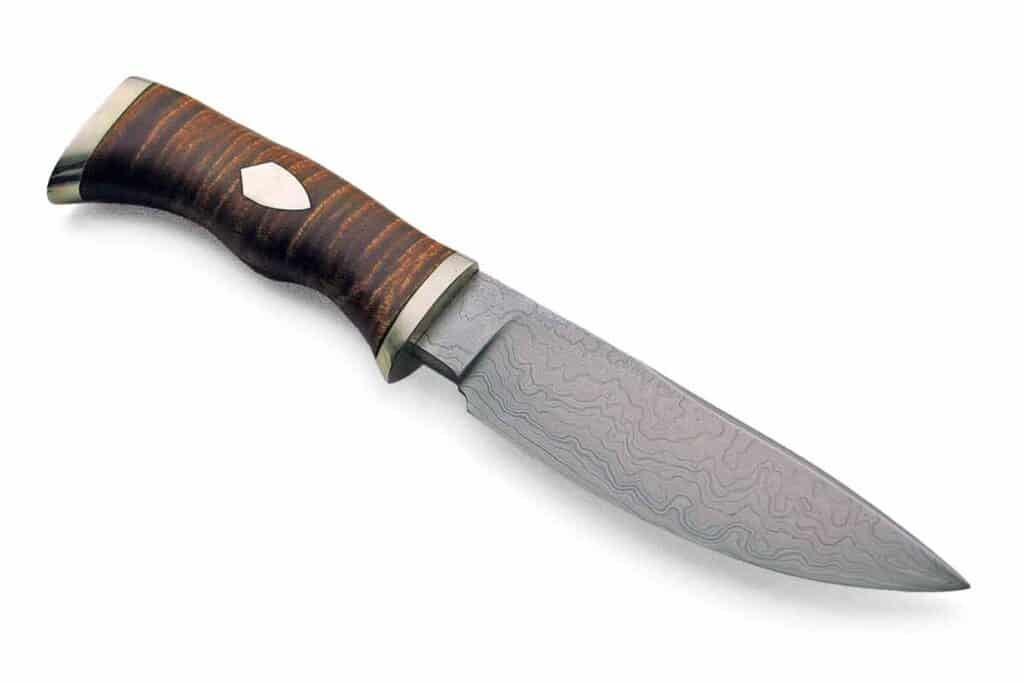

Collectors such as Cutlery Hall-of-Famer Butch and Rita Winter bought the first of Moran’s damascus knives during that historic Guild Show more than a half-century ago, and, as Hughes relates, “Moran made basic damascus knives. Most of his were what folks would call ‘using’ knives. They weren’t elaborate and this, that, and the other thing, but most of them were for use. He did make some art daggers that I thought were a bit elaborate for the day.”

Hughes remembers that Moran himself was rather vague on the number of damascus knives he actually made. However, probably the best estimate is that fewer than 100 Moran damascus knives were made during a career that spanned more than 50 years.

“He liked the random pattern and the ladder pattern,” B. R. remembered, “and he could do some pretty good patterns, but it took a lot of time. He was very happy just making ladder pattern and stuff like that, and he continued making non-damascus knives and about 40 folders. When he was in his shop, there were always five or six locals in there talking to him and watching him work.” Agreed Cutlery Hall-of-Famer and ABS master smith Jay Hendrickson, a close friend of Moran for 30 years, “Bill had so many visitors to his shop on a daily basis that it is a wonder he ever got anything accomplished.”

Hendrickson served as the executor of Moran’s estate and founded the Moran Foundation to preserve the great bladesmith’s legacy, serving as its president for 10 years. Jay observed that Moran made a workingman’s knife with quality that was spot-on, though there may have been an occasional flaw in the solder on his early pieces. Nonetheless, Jay says, Bill’s knives always cut.

As for Moran’s damascus knife productivity, Hendrickson offered, “This is strictly a judgment call on my part, but I would say Bill made less than 100 damascus knives. I counted 36 in our Forever A Legend book. I only know a few people that own Bill’s damascus knives, but I think they are sold and traded often between collectors. You also see Bill’s damascus knives occasionally sold at auctions.”

Jay verifies the original sale of a Moran damascus quillon dagger and sheath to Butch and Rita Winter and adds a bit more information. “Rita Winter recently sold Bill’s first damascus dagger to Mr. Doug Hook, a Tennessee collector,” he commented. “Two years ago, I repaired one of the twisted wires on the handle for Mr. Hook. Because of that contact I was able to confirm the original purchase as Doug has written verification of the original sales transaction and the invoice.”

So where are the majority of Moran’s damascus treasures today? Longtime purveyor Dave Harvey of nordicknives.com is straightforward—“in collections around the world. Values vary and depend largely on the particular knife. But they are generally worth at least double that of [one of Moran’s straight carbon steel blades], sometimes even more.”

Back in the day, a Moran damascus knife was a challenge to own, considering the time Moran spent in his shop with the material actually able to work without the distraction of visitors, the many hours of labor required to produce a damascus billet, and the higher price for such a piece that naturally followed. Dave Ellis of Exquisiteknives.com reasoned, “I could not say how many damascus knives Moran made in his lifetime, but certainly not a large number. Many of Moran’s damascus pieces reside in private collections, as well as the Moran Museum. I personally have owned and still own some and have sold a number of the finer pieces to overseas clients.

“I believe he made four or five patterns. Damascus steel was and still is a laborious process. Bill’s prices for his damascus knives were quite high for the time, so he made and sold mostly carbon steel pieces. Damascus was reserved for higher-end clientele and foreign dignitaries. A good number of the damascus knives were fighters and bowies. Damascus hunters were also made, many with Bill’s twist pattern steel, maidenhair. I do not know of any mosaic steel knives that Moran made. The first of the Moran damascus knives are quite valuable, and I would guess that they would start at least at $10,000 and go up from there.”

HOW HE MADE THEM

Hendrickson is familiar with Moran’s most common damascus patterns, the maidenhair twist, ladder pattern and others. “He knew how to fuse metal, as he learned that technique working on equipment on the family farm,” Jay remarked. “On the farm he made knives from whatever he could get his hands on, old springs, files, and rasps, for example. He could also buy steel from a local hardware store in town. Bill also knew the difference between plain iron and high carbon steel. His first damascus experience began by using one piece of steel and one piece of iron. He welded the two together, drew it out and folded it many times.”

The process yielded insight for Moran, and he learned from experience. At times during the process of hammering and folding, he realized that the steel was absorbing heat quicker than the iron because it was on the outside of the billet. Therefore, he moved to one piece of iron with steel in the center, and then a second piece of iron, using O1 tool steel and a carbon mix of 33 percent. According to Jay, this combination gave the billet the right hardness without the need for tempering. Moran’s test of the finished knife was to carve wood for two hours with no loss to the cutting edge, and he was satisfied with the results using this mixture.

“Bill made all of his damascus in a coal fire,” Hendrickson recalled. “A hot coal fire can melt steel as temperatures can reach over 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit, which is the melting point of steel. That is why Bill added iron to the outside of the billet, as iron is less apt to burn as quickly as steel. All of Bill’s experiments were with coal, as gas forges were not popular at the time. In today’s world, gas forges are almost always used for damascus making because of adjustable temperature and the cleanliness of propane gas. Therefore, the burning of steel to a great deal has been eliminated with the use of gas forges.”

Hendrickson attributes the relative scarcity of Moran damascus knives to the maker’s affinity for producing using knives, constraints on time and other factors. “Bill was truly a supporter of the art knife,” he noted, “and along with others they created that industry. Collectors were willing to pay big time for exceptionally well-made knives, and Bill, like other top-notch makers, profited as this industry took hold. However, Bill’s true passion was in using knives, such as camp knives, hunters and small utility knives, of which he made many. The vast majority of his knives came from customers wanting working knives.

“Bill liked to experiment with damascus. For example, he would slip in an added piece of iron after many folds to gain toughness in the end product. Another example was where he completed a damascus billet to the desired number of welds. He then cut it in two and added a piece of high carbon steel to form the middle and welded the two damascus pieces on both sides of the high carbon steel. Once that was completed, Bill forged the billet into a knife. One might call the finished product a damascus san-mai. Bill liked the various patterns that were being developed beyond the more basic patterns that he originally developed. To Bill, mosaic knives were art knives, not to be used but just admired. He didn’t like the process of welding pieces together to make a knife. Remember, he was more into using knives where the grain within the steel followed the entire edge of the blade.”

Through the years, Moran became a legend, leaving a legacy of learning, teaching, giving information freely, and welcoming many to his shop. He paid tribute in steel to the wonder of damascus, the art knife and the using knife. Today’s body of bladesmiths still looks to him as the guiding light that led them to the glow of the forge and the spark of the hammer on hot steel. Those who own or admire the few damascus knives that Moran completed continue to do so for their beauty, their imagination, their rarity, and simply because they bear the touch of the master’s hand.

More On Knifemaking:

- How To: Dellana Dots Opening System

- D.I.Y. POWER HAMMER: DO YOU REALLY NEED ONE?

- STAINLESS DAMASCUS: CHALLENGES IN FORGING

- STROPPING: WHAT IT IS AND HOW IT’S ACCOMPLISHED

- DIY ENGRAVING VISE OR BLOCK

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

BLADE’s annual Knife Guide Issue features the newest knives and sharpeners, plus knife and axe reviews, knife sheaths, kit knives and a Knife Industry Directory.Get your FREE digital PDF instant download of the annual Knife Guide. No, really! We will email it to you right now when you subscribe to the BLADE email newsletter.

Great read thank you