As with most things knife, one type never fits all.

BY MIKE HASKEW BLADE® FIELD EDITOR

Finding the best blade grind for the job at hand has become the subject of some debate, but most knife users agree that certain grinds are better suited for certain functions. Combinations of steel, knife design and use influence the choice of grind.

“I’m a proponent of the right grind for the right job,” related author/knifemaker Abe Elias. “In small bushcraft knives, a thin, flat grind and a saber grind are hard to beat. It makes sense that clear cuts are best flat edged. Carving chisels have rounded convex edges to go into wood and take small cuts and come out.”

An inappropriate grind may produce drag, a ragged or erratic cut, and generally poor results. “For overall working of wood and good, straight, controlled cuts, you want a knife grind to ride flat against the surface so it cuts past certain levels and growth lines, riding flat on the wood between growth lines,” Elias added. “It’s just physics. That’s all, and nobody can really argue it.”

One of the most popular grinds for bushcraft knives is the scandi grind, and Elias describes it as a perfectly flat grind with no secondary bevel, starting at the shoulder with an angle that is perfectly flat and straight to zero.

“Scandi grinds will go on any steel you want, but there are limitations to them because of the shoulder,” he noted. “It doesn’t tend to go through soft surfaces well, such as processing meat. When the knife enters a malleable surface, it creates too much drag on the blade. Like anything else, the thinner it is the easier it enters into other masses. We run into problems when custom makers make them and factories produce them without following the golden rule of proportion. The angle should be proportional to the thickness of the steel and the design of the knife itself.”

CONVEX MODIFIED

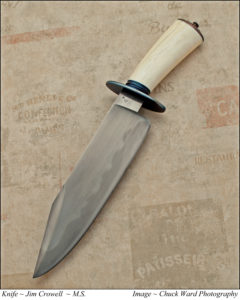

Influenced heavily by BLADE Magazine Cutlery Hall-Of-Fame® member Bill Moran, Bill Bagwell, and Don Hastings, ABS master smith Jim Crowell recognized early in his knifemaking career that the intent was to make a full convex grind from the spine of the blade to the cutting edge. He has adapted those original lessons through the years.

“I’ve found that it’s the edge that needs to be convex, not necessarily the whole cross section of the blade,” Jim noted. “Consequently, I have now, for many years, ground my blades flat from spine to cutting edge, stopping short of going to zero and then rolling the cutting edge on convexly. The trick is to get the geometry correct for the thickness the edge was ground to prior to sharpening in conjunction with the type and heat treat of the steel used.”

Crowell says he believes the convex grind is best for knives in the field, including bowies, fighters, and fillet knives. He uses the convex grind almost exclusively and indicates it allows for an uninterrupted transition from the cutting edge to the full thickness of the spine of the knife. No matter how thick or thin the spine of the knife, with convex geometry it will have the least amount of resistance when cutting through an object.

As for sharpness, Jim gives the nod to the scandi grind. However, he believes that when the cutting edge is, in fact, the grind line as well, the edge itself is more fragile in comparison to other grinds.

“Scandi grinds are great,” he said, “and useful for a lot of small chores. Then there are special-purpose applications like some sushi knives that have specialized grinds. Still, for day in and day out I like and recommend the flat, convex grind.”

COMFORT MATTERS

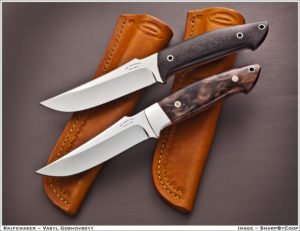

Knifemakers tend to use the grinds they are comfortable with and which they believe fill the bill for the types of knives they make. The degree of difficulty associated with a particular grind lies more in the experience of the maker than in the grind itself.

“The hardest grind is the one you do not regularly do, and the easiest would be the one you do all the time,” Crowell reasoned. “When I started, I used to hollow grind stock removal blades. You could lay everything out and follow the lines—it is still hard though. When I started forging it was really hard because there were no layout lines to follow, and all the scale and hammer marks made it hard to tell what I was doing. Daggers are generally acknowledged to be more difficult. Some of the Russian and Persian stuff with a ‘T’ spine or center ridge would be tough.”

“The hardest grind is the one you do not regularly do, and the easiest would be the one you do all the time.”—Jim Crowell

FACTORY APPROACH

Knife manufacturers gear their grinds for prospective use as well. Hollow grinds are usually the most efficient for manufacturing because both sides of the blade are ground at the same time. Flat grinds are ground one side at a time, and precise machining and good tooling create the even grinds for which manufacturers are known. Convex grinds are usually finished by hand, and such work is the province of a skilled custom maker.

“Hollow grinds are great for slicing,” commented Jim MacNair, new product coordinator and senior designer at KAI-USA Kershaw, “and they create a nice, thin edge geometry, and the panel of the grind stays thinner as you sharpen away the blade over time. These blades will feel very sharp because the grind scoops away more material and makes the blade thinner overall.

“The most obvious benefit of the flat grind is strength and toughness. The wheel is grinding a flat surface rather than a concave one like a hollow grind, and it removes less material from the blade. That added material makes the blade thicker and stronger.”

MacNair sees compound grinds emerging in the custom market, including blades that feature a combination of flat- and hollow-ground bevels. These are often done to create a “cool” look, and the maker is also providing the best of both cutting options: a thin, hollow-ground edge for slicing and a thick, flat-ground tip for toughness.

Innovation continues to find its way into new and user-friendly blade grinds, while the emphasis on the job to be done is at the center of the decision. Putting the proper edge on the blade for cutting, slicing, skinning, chopping or any other task will always be primary.

SWORD GRINDS HOSTETTER’s WAY

Swordsmith Wally Hostetter focuses on Japanese blades and tailors the grind of each to its anticipated function. He forges the blades and sets up the edge geometry with hand filing.

“A lot of guys do hollow or flat grinds with a machine, but what I do has to be done by hand,” Wally explained. “I hand polish to the cutting edge, and there is no micro-bevel. Some have an appleseed [convex] edge—niku is the Japanese term—and some have the edge slightly rolled in for better cutting. For cutting heavy stuff, the niku comes to a finite edge but runs farther up the blade. There are many subtleties to it.”

According to Hostetter, other Japanese grinds, such as that found on the tanto, are fine and done to a thin edge because they are not intended for hard striking against surfaces. He uses 1095 carbon steel primarily and decides on the appropriate grind based on both the use of the blade and the historical time period that is being replicated.

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

BLADE’s annual Knife Guide Issue features the newest knives and sharpeners, plus knife and axe reviews, knife sheaths, kit knives and a Knife Industry Directory.Get your FREE digital PDF instant download of the annual Knife Guide. No, really! We will email it to you right now when you subscribe to the BLADE email newsletter.