The Roots of Modern Custom Knives

The branches of the modern custom knifemaking family tree spread far and wide. Its sturdy roots, though, are found in the little town of Fruitport, Michigan. There BLADE Magazine Cutlery Hall Of Fame© member William Wales Scagel applied his steady hand and artisan’s eye to the first knives of the modern era that were truly exemplary examples of those classified today as “custom.”

Scagel’s influence resonates across the decades as knives and knifemakers have taken their cue from his mastery of the curve and the spacer, his interpretation of the lines, fit and finish of a knife that stands the test of time, setting a standard for others to follow. Born in 1873, Scagel lived to the age of 90, and during his lifetime proved himself a master metalworker. His wrought iron adorned the windows of banks and other buildings in the city of Grand Rapids, and he participated in bridge building as well. His first knives were made in lumber camps in the Great Lakes area of the USA and Canada, with the earliest examples dating to around 1910.

Th rough the years Scagel made his imprint as a custom knifemaker, selling his wares through Abercrombie & Fitch during the 1920s, raising the profile of the custom knife with his recognizable style of stag and spacer handles. His friends at Brunswick Corp. kept him supplied with scrap pieces of Bakelite (the first manmade plastic and first true synthetic), wood, ivory and fiber from the manufacture of pool tables and bowling balls for use as spacers. He made bowies, hunters, fighters, folders and hatchets that have become coveted collectibles fetching high prices at auctions and private sales. His kitchen knives were second to none, and his paired carving sets were expensive masterpieces.

Meanwhile, those who appreciated a tough working knife that had a distinctive look gravitated toward custom knifemaking. Among them was legendary Cutlery Hall-Of-Famer Bo Randall, who became a protégé of Scagel. In turn, Randall influenced the likes of Cutlery Hall-Of-Famer Bob Loveless and so many others—and the legacy continues to grow.

Scagel, the Man

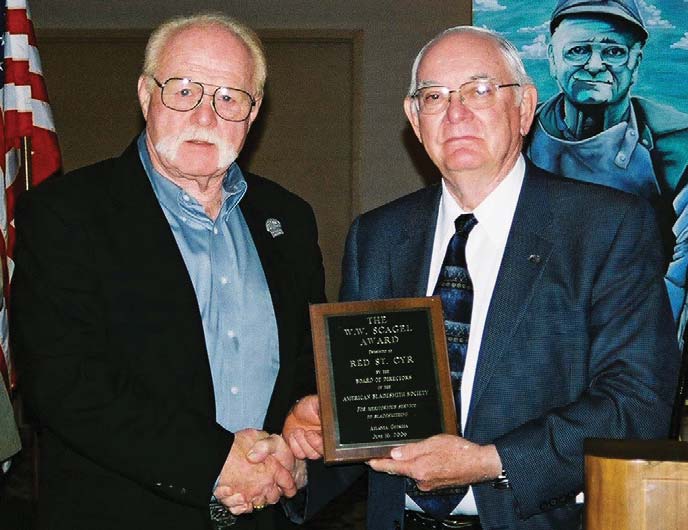

Dr. Jim Lucie, Scagel’s longtime friend and personal physician, remembers a matter-of-fact kind of guy.

“He was sometimes quite opinionated,” recalled Dr. Lucie, who achieved status as an ABS journeyman smith in his own right. “He shunned publicity and did not like the public eye, and he was critical of some types of people. He was an atheist by choice and didn’t mind stirring the pot about something. If he liked you, and I spent many delightful hours with him, he would go to hell and back for you. If he didn’t, you only got one chance to take advantage of him.”

of the only known pictures of the famous knifemaker.

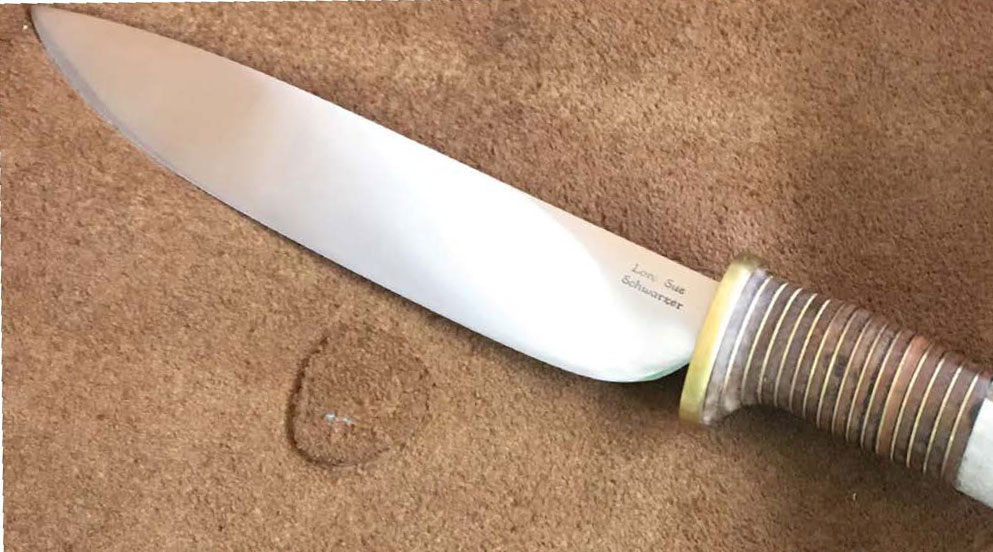

Scagel’s signature stacked handle. (Mike Carter image)

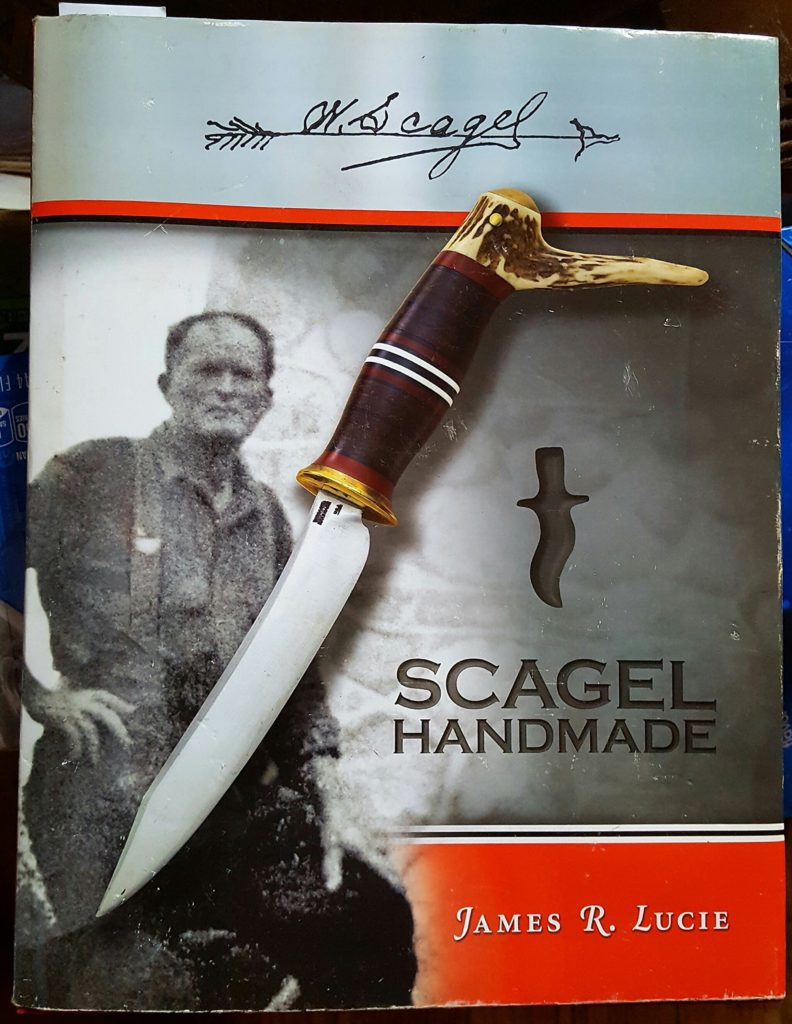

The author of the quintessential book on the subject, Scagel Handmade, published in 2010, Dr. Lucie calls Scagel a “genius with metal work. He was a pioneer. He got Bo Randall started, and the first knives Bo made were around 1937-38, I believe. Scagel’s knives have been copied more than anybody else, more than even the Bob Loveless drop point.”

Now 90, Dr. Lucie sold his extensive Scagel collection in 2011, and he confirms that the great custom maker once said, “There are no straight lines in nature, and neither should there be on any knife.”

Scagel’s work has often been imitated, sometimes with dubious results. At other times, however, the style has been replicated with precision. ABS journeyman smith Lora Schwarzer worked in a hospital with Dr. Lucie, who introduced her to Scagel knives.

“Dr. Lucie helped me get started, and I wanted to do Scagel-style knives,” Lora remarked. “They are pretty and easy to hold. They feel good in your hand, and none of them are the same, basically. He might have done a few sets that match, but that was not the norm. The spacers are different and the antlers are different, and they are pretty with their curves and colors.”

Schwarzer started forging in 1996 and has made many Scagel repros since then. Her current work includes a couple with 1084 tool steel blades, brass guards, and leather, fiber, brass, copper and bronze spacers. Her favorite Scagel knife is an unmarked piece.

“If someone brought him a piece of steel,” she explained, “and asked him to make a knife for them, he would do it but not mark it because he didn’t know what kind of steel it was or where it came from. I got this one from Dr. Lucie, who got it from the person Bill originally made it for. Its handle is alternating brass and leather spacers with deer antler at the other end. That was his signature stacked handle.”

One of the great stories Lora likes to tell about Scagel involves a lady who regularly visited the local grocery store. In those days it was common to wrap purchases in brown paper and tie them with string. The lady struggled to break the string, so Scagel made her a miniature knife, which Lora has seen and is pictured in Dr. Lucie’s book, to cut the strings.

“Another thing I know is that Bill Scagel had a kind heart,” she added. “During the polio epidemic in the 1950s, he built braces for people without charging them.”

Scagel Knives

Gordon White of Cuthbert, Georgia, has been collecting Scagel knives for about 30 years. Gordon sees the historic significance of Scagel’s body of work as a big reason for his lasting interest.

“Well, the knives are just so unusual and different,” he said, “and he is the father of handmade knives and the first person in the 20th century to start making a custom handmade knife. He forged everything he made, and the unique fact that he made his own machinery and equipment and did everything by hand tells me that there has really been nothing like Scagel before or since.”

According to White, one of Scagel’s most innovative tools was used to place the spacers on the knife handle and then press them together, followed by the stag or brass butt that was then pinned in place. Scagel hatchets in mint condition are difficult to find because they were meant for use, and those who bought them put them to work steadily.

Unlike other custom makers who can point to a mentor or individual who helped launch their careers, collector Louis Chow says Scagel stands alone.

“He was unique, you could say, because in my opinion I don’t think Scagel was too much influenced by anyone else in the beginning. Still, there were great knives being made before Scagel. For some reason, he was somewhat of a hermit and didn’t research what other guys were starting to do. Of course, those famous makers had the power tools necessary to make precision knives. Scagel used whatever he had on hand, a small generator and grinder. He didn’t have anything to go by as a sample, no publications to refer to. So, he basically did what he thought a hunter or bowie knife would look like.”

Chow is primarily a Loveless collector, and he acknowledges that the reasons for collecting a particular custom maker are varied. He agrees with White that the history of Scagel is a big factor.

“If I look back at how Loveless got started, as far back as you can go, Scagel is the granddaddy of the industry and influenced everyone else,” Chow explained. “For me, he is the source of what influenced Loveless. My preference is Scagel’s simple daggers that he made during World War II, his contribution to the war effort and the foundation of the current custom knife industry.”

Chow owns three Scagel daggers from the World War II era and a small pocket hatchet that was popularized in the 1950s. The daggers are forged carbon steel with full tang handles slabbed in wood. The construction of the guards is unusual with a wrap-around opening to fit onto the tang.

“Two of the three daggers are made like that,” Chow said. “It’s just another aspect of Scagel’s work, something different.”

Values of Scagel Knives

Scagel knives remain popular among collectors, and White considers the prices paid at the 2011 auction of Dr. Lucie’s collection as evidence of the demand.

“That auction is a good meter to go by,” he remarked. “The hunters were averaging from $12,000 to the mid-$20,000 range depending on appearance, and condition has a lot to do with it. Some of them look better than others, and a high-quality sheath with good looks adds to the value. Dr. Lucie had some fighters in his collection, and they probably averaged $28,000 apiece. One fighter brought $41,400.”

Schwarzer sees continuing appeal in Scagel knives simply because there is nothing else quite like them.

“They are different, and I have been at shows and seen people really get excited about them,” she commented. “Some people like them and some don’t, maybe like pizza with thick crust or thin. It is a matter of personal preference, but Scagel knives certainly have staying power.”

Staying power, pioneer power, legendary power: They are each part of the Scagel legacy, one that is like no other in the history of custom knives.

Learn More About Classic Knives

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

BLADE’s annual Knife Guide Issue features the newest knives and sharpeners, plus knife and axe reviews, knife sheaths, kit knives and a Knife Industry Directory.Get your FREE digital PDF instant download of the annual Knife Guide. No, really! We will email it to you right now when you subscribe to the BLADE email newsletter.