Safety feature, bell and whistle, or what have you, the half stop stimulates lively discussion.

What is a Half Stop?

An old song includes the lyric, “It certainly is exquisite, but what in the dickens is it?”

The slip-joint knife version of the phrase can easily be attributed to the function, or lack thereof, surrounding the half stop, the flattened shaping of the tang that allows the blade to stop in mid deployment.

It’s a safety feature; it relieves pressure on the spring; it’s a mark of fit and finish that the best slip joint makers always include; or, just maybe, it’s like your appendix. It once had a job, but nobody really knows what that job was. It hangs around—and in some cases it has been removed.

What a Half Stop Does

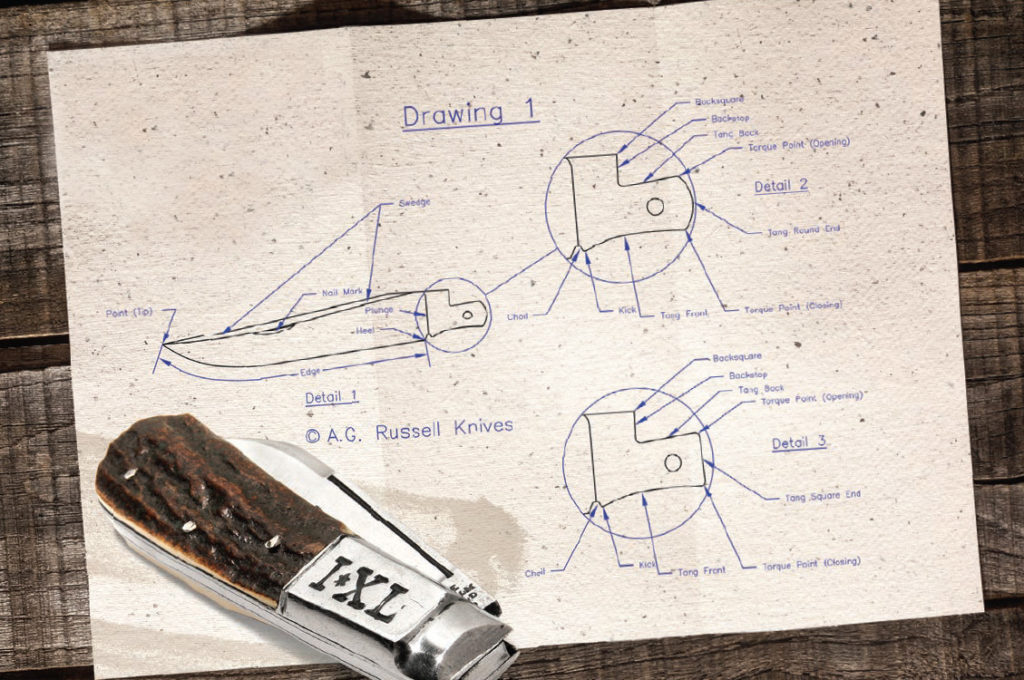

square end. (A.G. Russell Knives image)

“In a traditional slip-joint knife, a half stop indicates the blade has a square tang instead of a conventional rounded one,” explained Phil Gibbs, a veteran knife designer who has worked for A.G. Russell Knives for a number of years now.

“There are two reasons for a square tang. One is that a pause to move your fingers out of the way is desired halfway between open and closed. The second is that the knife has a flush end. Most issues of a square tang not working properly can be traced to poor spring/tang design and/or poor execution.”

There are plenty of ideas and opinions out there, and longtime custom knifemaker Gray Taylor admits the purpose of the half stop is something of a mystery to him.

“A half stop is just a low place in the back of the blade, a flat place that stops the blade and takes tension offthe spring,” he observed. “It just protects your spring from breaking, in my opinion, or it could be called a safety feature. Old guys have told me that if you have a whittler pattern, for example, with one blade on either end, you don’t want to open a knife halfway because you double the tension on the spring.”

The History of the Flat Stop

The history of the half stop is as murky as its real role in the life of the slip joint. For sure, it has been around at least a couple of centuries, dating back at least to the knifemakers of old Sheffield—possibly much earlier.

Museum curator, researcher, and knife historian Pete Cohan points to traditional knives and modern multi-blades that have square backs; therefore, a half stop would have no purpose on them.

For Cohan, the “time factor” is relative, depending on how far back one would have to go.

“The amazing thing is that over a long period of time that feature was not present, and that is a fact,” he commented. “I was puzzled by this a long time ago and couldn’t find any indication of a patent associated with the half stop. At one point, I assumed it was a safety feature, and that was about the only thing I could come up with as to intent. I know similar things have been used in lock making, and that makes sense because you are pushing something to allow it to drop into a location to lock or unlock.”

Gibbs isn’t sure anybody knows the real origin of the half stop, but the earliest example he has seen through the years is on an 1800s barlow with a flush end made in Sheffield.

Veteran multi-blade slipjoint maker Bill Ruple has also seen the Sheffield connection but doesn’t know much more than that regarding the half stop’s history. Nonetheless, he does find function in its continuing existence.

“I have heard the half stop called a ‘safety catch,’ and my theory is that it was invented to be easier on the spring of a multi-blade knife,” Ruple offered. “The blade should literally jump into the half-open position and have no play or wiggle. If you can feel any wiggle or movement, it’s not right.”

Half Stop Debate

For years, Ruple and A.G. Russell engaged in a congenial debate regarding the half stop. They never resolved their difference of opinion, and it remains one of Bill’s fondest memories of his relationship with the BLADE Magazine Cutlery Hall-Of-Fame® member.

“I personally use half stops on all my slip joint knives, unless the customer wants a full tang, and I have been doing it for 33 years,” Ruple commented. “The late Mr. Russell, however, would disagree with me on this one. A.G. was a good friend of mine for many years, and every time I saw him, he would give me a hard time about using half stops. He hated them.”

Gibbs acknowledges Russell’s disdain for the half stop and says it lies in a bad experience that occurred years ago.

“A.G. was not a fan of square-end tangs due to being severely cut by an extremely poorly designed and executed custom-made trapper,” Phil said. “He was cut because the maker apparently had no idea how to correctly design a pocketknife spring and tang to work well together. If your traditional knife works like a mousetrap, you are doing it wrong!”

Ruple is solid in his support for the half stop, relating, “Half stops are easier on springs, especially on rocker springs, which are springs with a blade on both ends. With the half stop, the spring is approximately the same, whether the blade is open, half open, or closed. With a full tang the spring has more pressure in the half-open position.”

Cohan concludes that the half stop has reached functional obsolescence. “Well, take a scout knife with four blades. Invariably, it has a half stop. Why? I can’t think of any reason they still make knives with half stops. Maybe it is more habit than requirement. My point is that the only answer I have ever come up with is the safety feature, and I’ve certainly never seen a patent on it.”

Some observers still assert that the half stop was a necessary revision to the tang, going so far as to state that it prevents the user from needing a pair of pliers to open a knife. Its absence, they say, would cause the spring to flex the entire distance of the end of the tang, and it functions to prevent the total failure of the spring, relieving pressure with the blade open that would otherwise fatigue and eventually compromise the spring’s integrity.

Gibbs scoffs and strongly disagrees.

“Converting to a square end tang in no way significantly reduces spring deflection,” he remarked. “It is the torque points of the tang that define the opening and closing force applied to the blade. A.G.’s tang designs employ a tangential radius to produce the round end of the tang joining the two torque points and resulting in zero increased spring force.

“Consequently,” Phil continued, “the round end tang and the square end tang would have identical opening and closing forces. Actually, with a square end tang the spring is flexed twice for each opening or closing, so I would surmise it increases stress to the spring. The only time there is any difference to the spring pressure on a square end tang compared to a round end tang is in the half-open position.”

Making the Half Stop

Through the years, the inclusion of the half stop has probably remained fairly constant, and those who pay attention to it can’t say for sure that its use is waxing or waning. Gibbs recalls that the square end tang was traditionally found on barlows and Remington trappers, and some custom knifemakers continue to incorporate it today.

While the pros may differ in the usefulness of the half stop, they can agree that making a slip joint that includes a half stop adds little or no difficulty or cost to the construction process.

“I wouldn’t say it’s a lot harder,” Taylor commented. “You’ve got to make sure the half stop is positioned that when your blade stops at the half stop, it wants to be perpendicular to your knife. If your grind is off five degrees, the blade won’t sit straight. You’ve got to make it perpendicular to the back of the knife to look right. On the other hand, if you don’t have a half stop and cut a cam on the back of the blade, you’ve got to make sure the cam allows just the right tension. It takes practice. Throw a few blades away and you’ll catch on.”

Gibbs, who actually hails from Sheffield, England, considers the flush end knife more difficult to make than one with a square end tang, so the price might be somewhat higher due to the maker’s skill set. Throughout his career, he has had ample opportunities to assess thousands of knife designs.

“In my previous position as cutlery engineer at [the old] Camillus Cutlery Company, I designed several knives with square end tangs,” he related. “I considered it a required feature on some of the Remington Bullet knife reproductions we produced. We also made the Camillus Double Lock Back Trapper with square end tangs. It was not any harder to make at all.”

you don’t want to open the knife halfway because you double the tension on the spring. This I*XL George Wostenholm antique in ivory is an example of a three-blade whittler. (Pete Cohan image)

The Future of the Half Stop

Relevant or passé, here or gone, the half stop is a pocketknife feature that is likely to generate some lively discourse. While it may or may not add anything to the performance or durability of a knife, it’s healthy for the industry simply due to the fact that it gets people talking.

BLADE’s annual Knife Guide Issue features the newest knives and sharpeners, plus knife and axe reviews, knife sheaths, kit knives and a Knife Industry Directory.Get your FREE digital PDF instant download of the annual Knife Guide. No, really! We will email it to you right now when you subscribe to the BLADE email newsletter.

Click Here to Subscribe and get your free digital 2024 Knife Guide!