Temper lines—aka hamons—are a very exciting part of knifemaking, and I would like to share with you how I produce cool temper lines on folders. -Wally Hayes

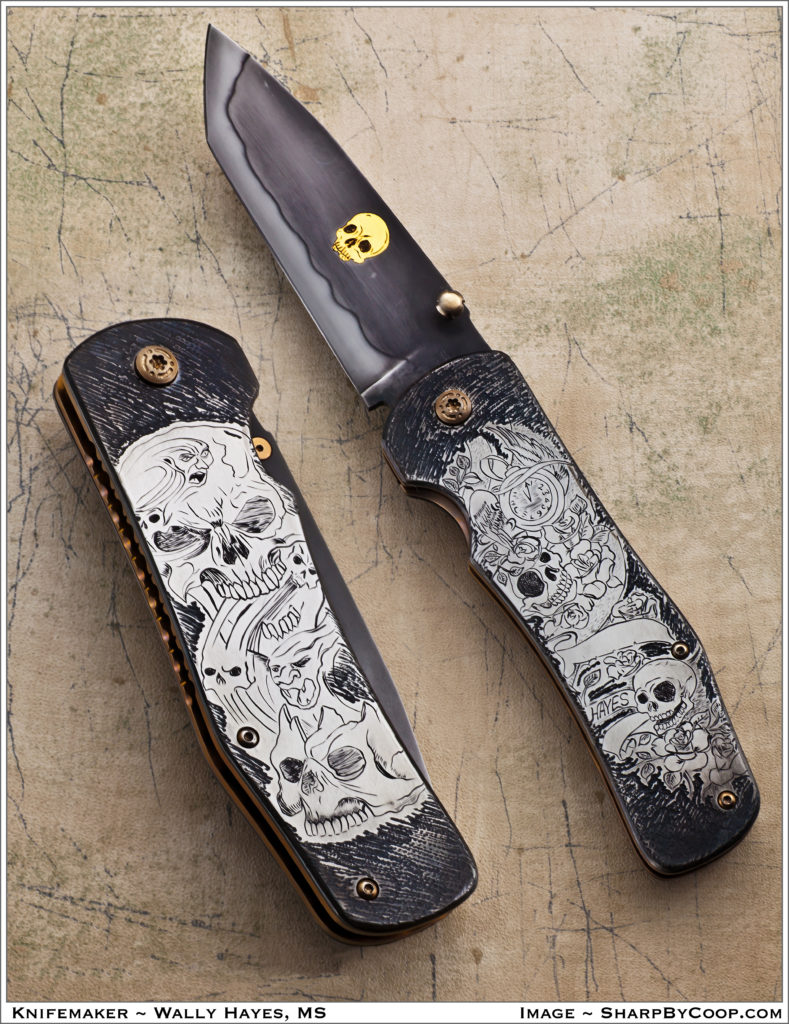

The latest folder exhibiting a handsome temper line—aka a hamon—by the author (inset) is this skull-encrusted model. (SharpByCoop knife image)

STEEL and CLAY

First you need to select your type of steel. You can use 1084 carbon steel or high-carbon damascus, but I prefer W2 tool steel. I get mine from New Jersey Steel Baron because I can get it surface ground to whatever thickness I need.

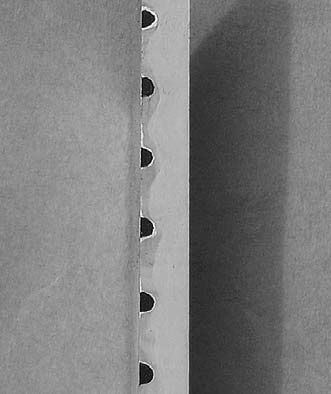

The W2 is low in manganese, enabling you to create wild temper lines. I grind the blade leaving the edge about the thickness of a dime. The thickness helps prevent your blade from warping in the quench and also helps hold the heat, giving you time to get the blade into the quenching oil.

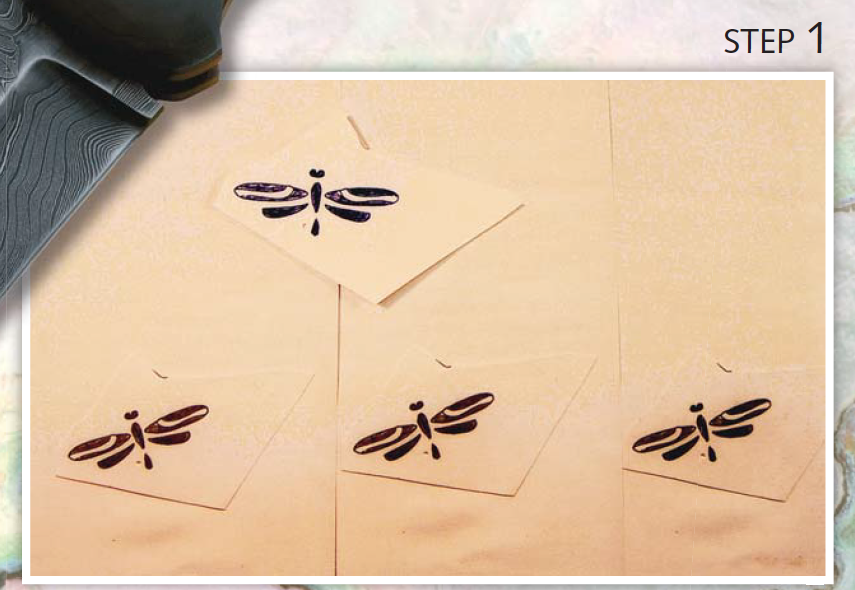

The clay I use is a stove furnace cement used to repair fireplaces and chimneys. I get mine at the hardware store and it comes in a small tub or a tube like the tubes of silicone used with a squeeze gun for calking.

APPLYING the CLAY

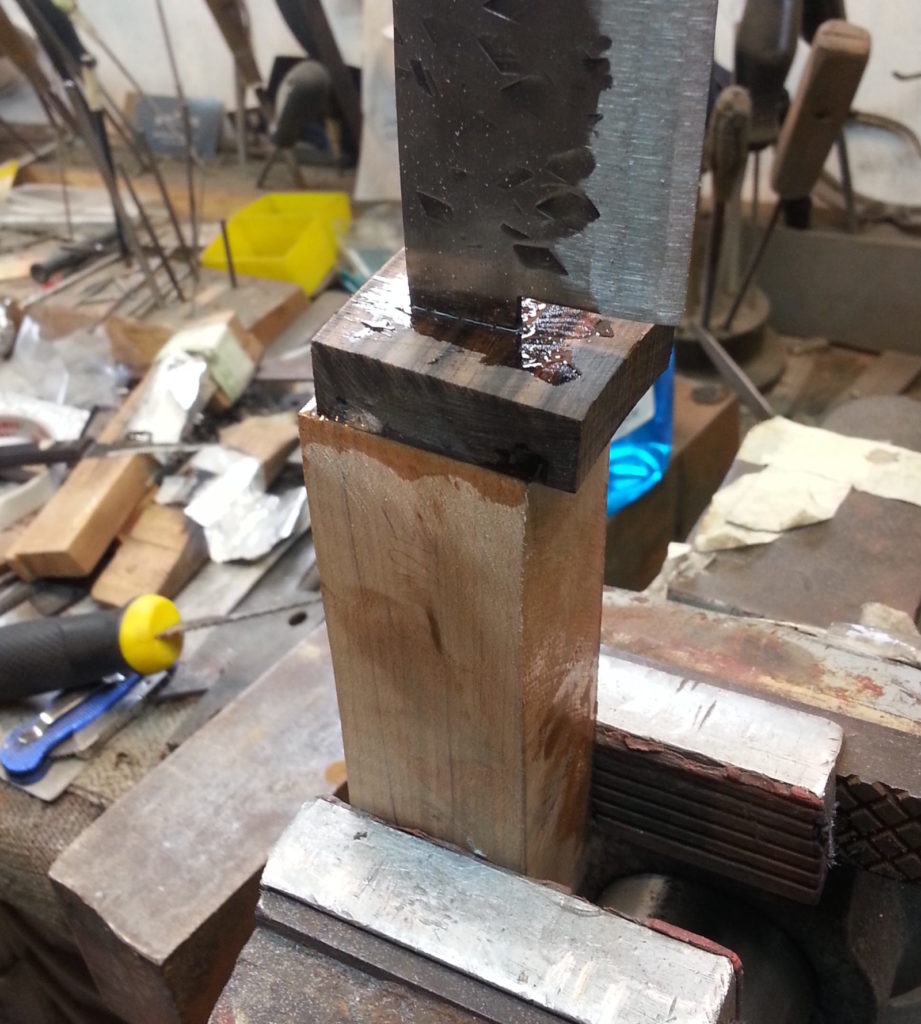

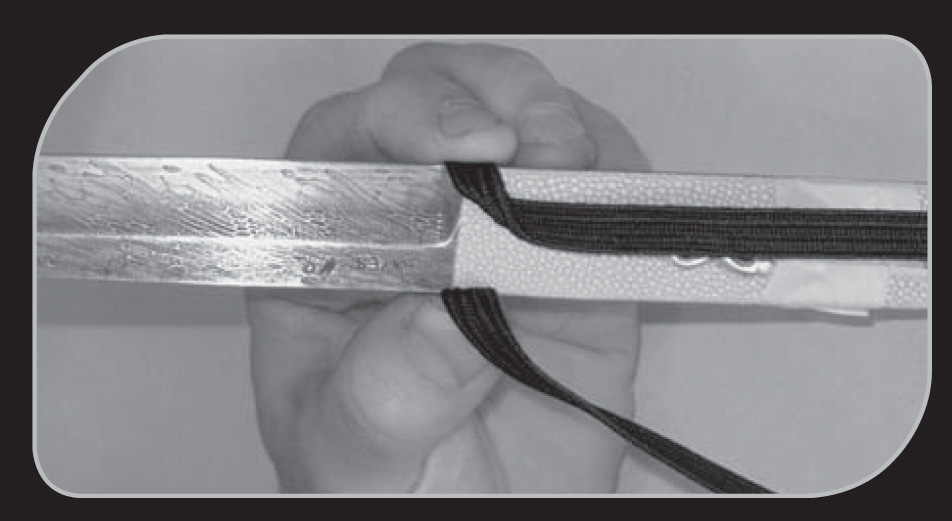

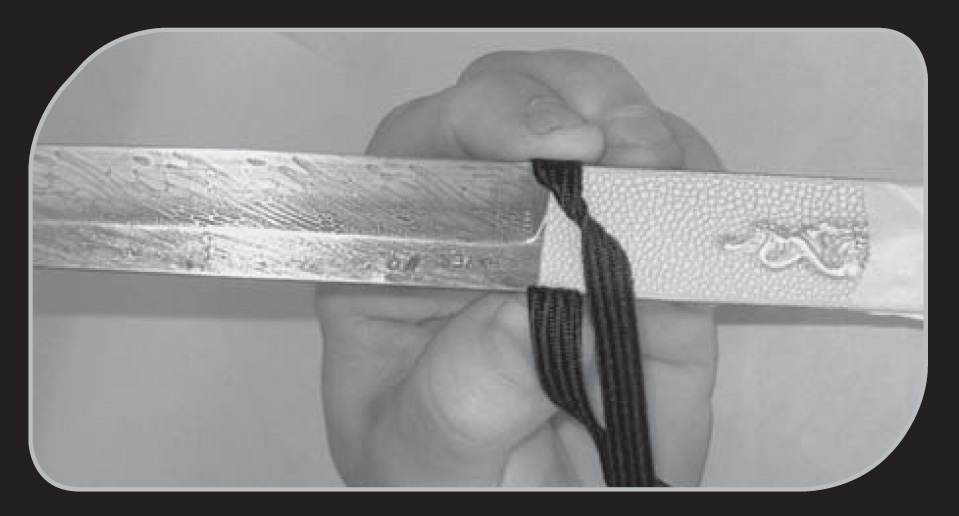

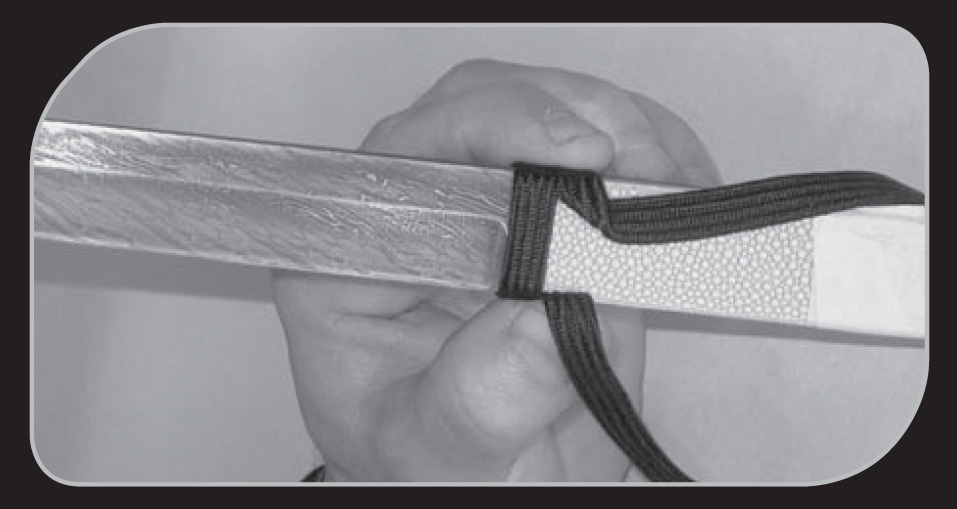

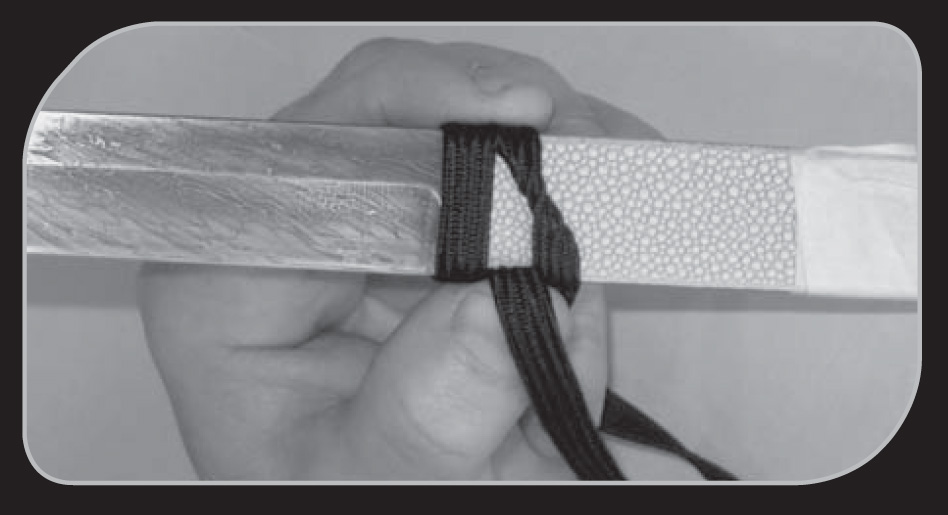

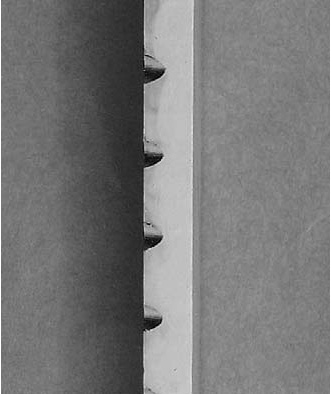

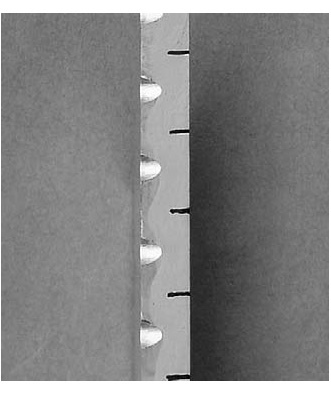

To apply the clay I use a sharpened Popsicle® stick, being careful not to put any clay where the ball bearing in the liner will travel on the tang of the blade. Also, do not put any clay near the pivot hole as you want that area to become fully hard when quenched.

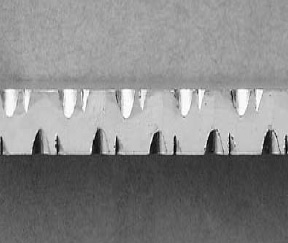

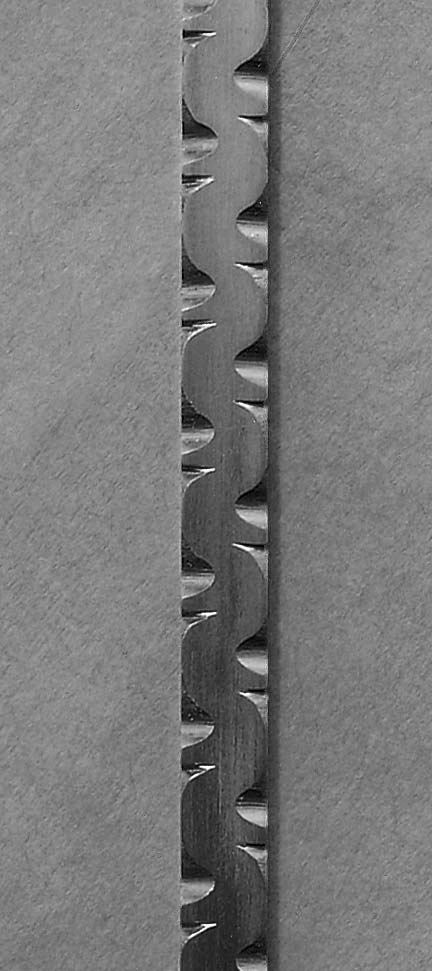

I like a very exaggerated temper line with big waves. You can achieve this by placing short lines of clay every half inch down the blade. Do not carry the clay line all the way to the edge as you want the edge fully hard.

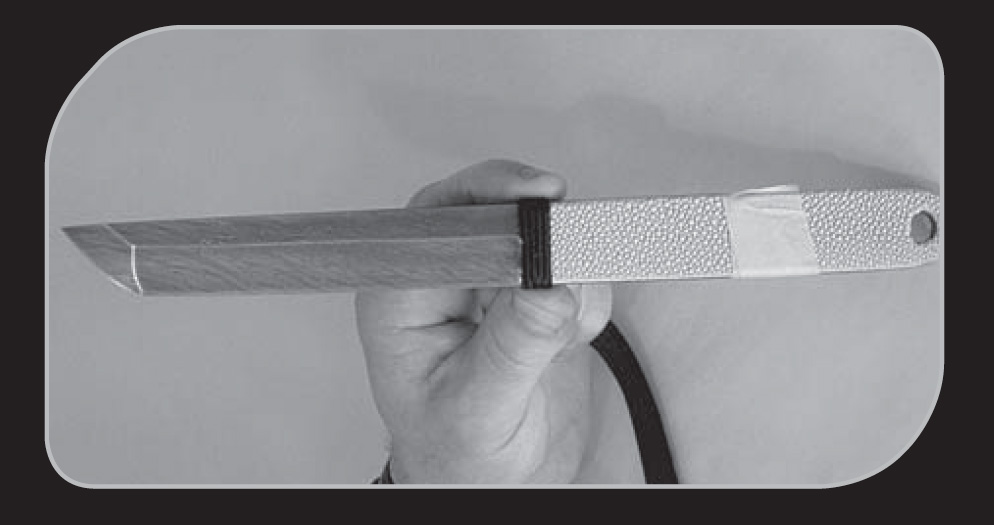

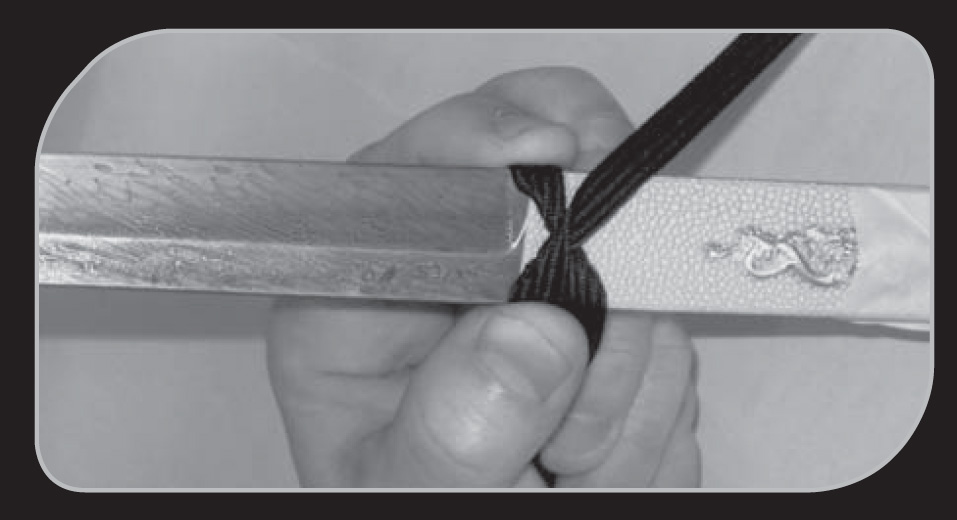

I put the clay on the blade about an eighth of an inch thick. This seems to work very well. Let the clay dry for about four hours before you heat treat it. To heat treat the blade I use a propane forge. I place a coat hanger through the pivot hole and twist it around the tang of the folder to give me something to hold onto.

HEAT and QUENCH

Gently heat the blade near the opening of the forge for a minute before placing it into the forge edge up. Watch the blade come up to temperature, placing the tang near the hottest part of your fire. The tang is the thickest area of the blade and slowest part to get up to critical temperature. Heat the blade until a magnet does not stick to it. I use a cow magnet on the end of a pipe and keep testing the blade as it heats up to temperature.

When a magnet does not stick to high carbon steel the steel is at critical temperature, at which point the blade should be removed from the forge and quenched in oil. For steel, I use a fast-quench oil such as the kind from Parker or Fensoil. I have also done many successful quenches in vegetable oil.

I quench the blade and then leave it submerged for two minutes before removing it. Once its out, I clean the blade with a paper towel. I then put the blade in the toaster oven for one hour at 385°F.

WARP CHECK, GRIND and POLISH

After the blade is cool I check it for straightness on a flat piece of steel. I use a set of parallels for this. If the blade is warped, I clamp it to a slightly curved piece of thick steel, and press the warp out with the twist clamp. Then I place the clamped blade in the toaster oven for another hour’s worth of temper at 350°F. This works really well and is less stressful to the blade when compared to trying to straighten it another way.

Once the blade is straight it is time to finish grind and polish it up to 2,000 grit. I do the final polishing by hand to ensure every scratch has been removed. After this I sharpen the edge and make sure it is also polished carefully. Finally, I use sand paper backed up by a thick piece of leather and sand very slowly so I don’t cut myself.

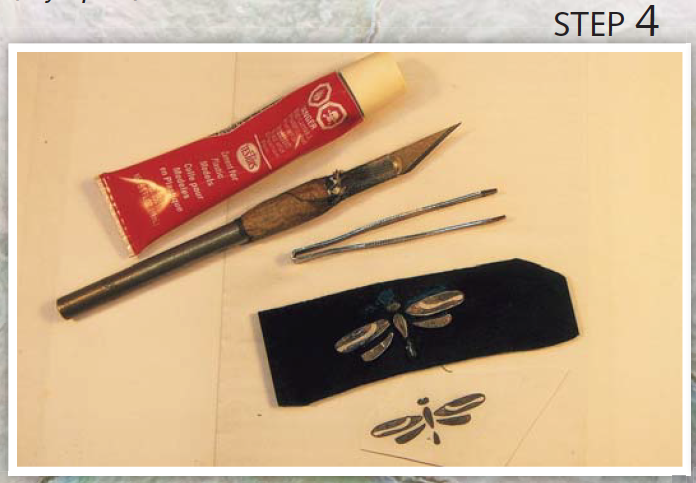

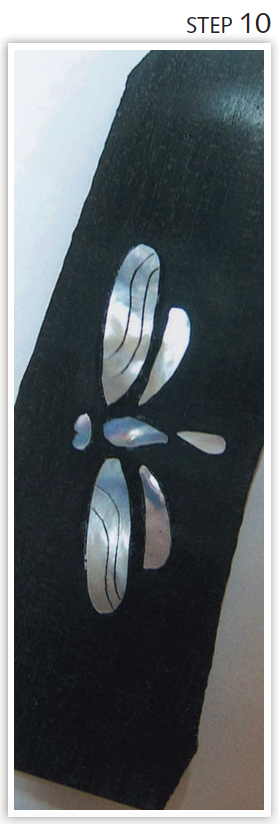

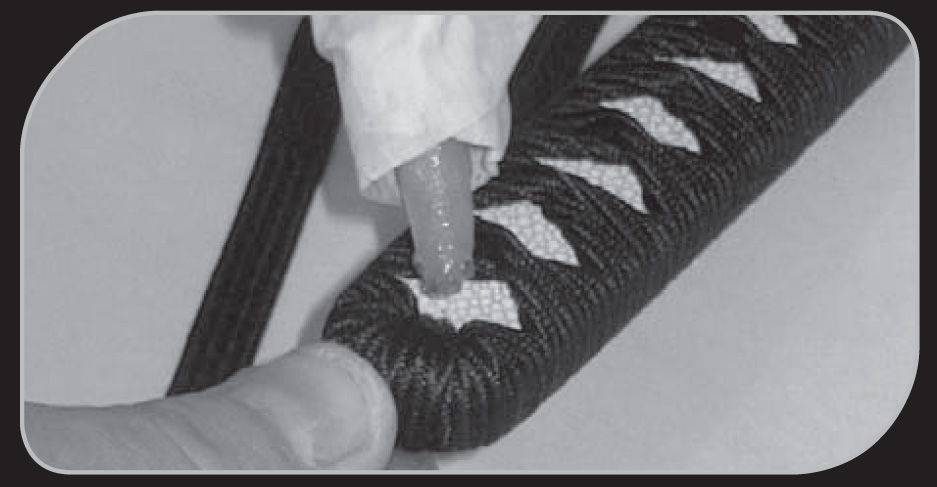

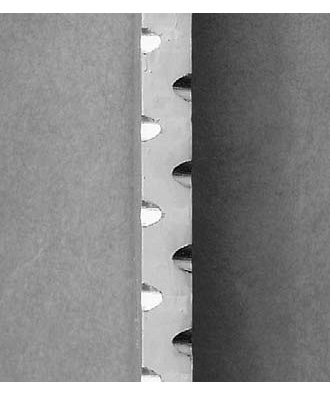

The ETCH

Next up: Etch the blade to bring out the temper line. Clean the blade with acetone. Wear latex gloves to protect your hands and to keep oils from your hands off the clean blade. To etch the blade I use ferric chloride diluted four-to-one with distilled water—that is, four parts water to one part ferric chloride. Hang the blade with a cotton string tied through the pivot hole and place it in the acid for 15 seconds. Remove the blade from the acid and spray it with Windex®. This neutralizes the acid and stops the etching. Dry the blade and coat it with WD-40®. Rub a little bit of polishing compound onto the blade to remove some of the residue from the etching. I use Flitz or Peek polishing paste with a paper towel and some WD-40. Polish lightly and be very mindful of the sharp edge. Clean the blade with WD-40 and wipe off any excess oil.

To get the temper line white, go over the blade lightly with a piece of 3,000-grit-or-higher sandpaper.

I hope this gives some insight into the fun world of temper lines and more people will experiment with this fun process.

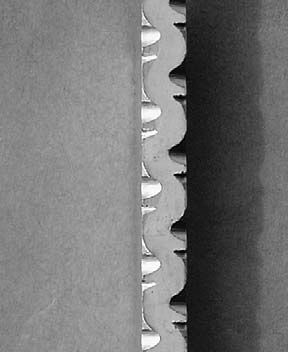

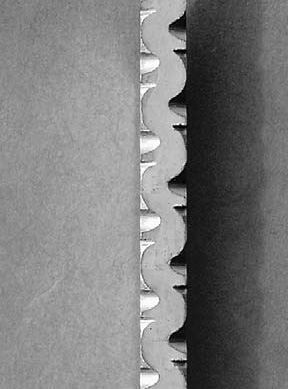

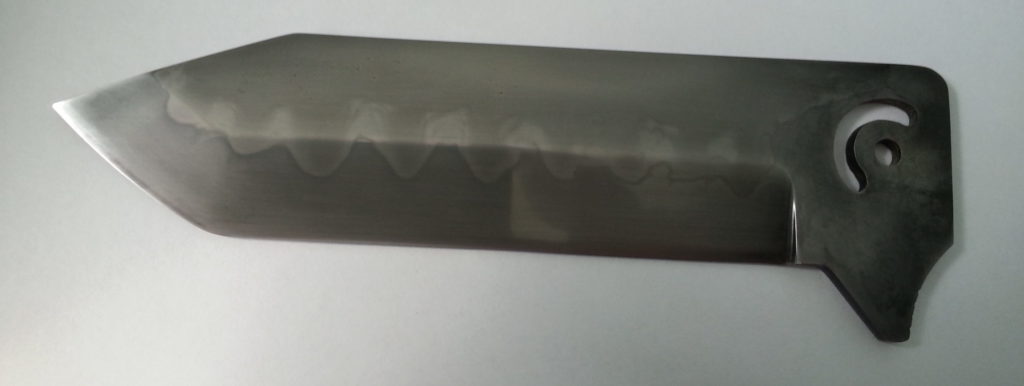

Above: The blade of the author’s finished folder exhibits a temper line with big waves—just the way he likes it.

For more information contact Wally Hayes, 9960,9th Concession, RR#1, Essex, ON, CanadaN8M-2X5 226-787-4289.