With the K-Tact Kukri, Condor goes both old school and modern.

As with all knives, the steel is only as strong as the hand that wields it—and perhaps with no knife is this so true as the kukri.

The kukri—aka khukuri—has a reputation so legendary that even some non-knife enthusiasts recognize the knife when they see one. To understand how the kukri got its reputation, let’s examine the people who used it and help grow the legend.

Kukri History

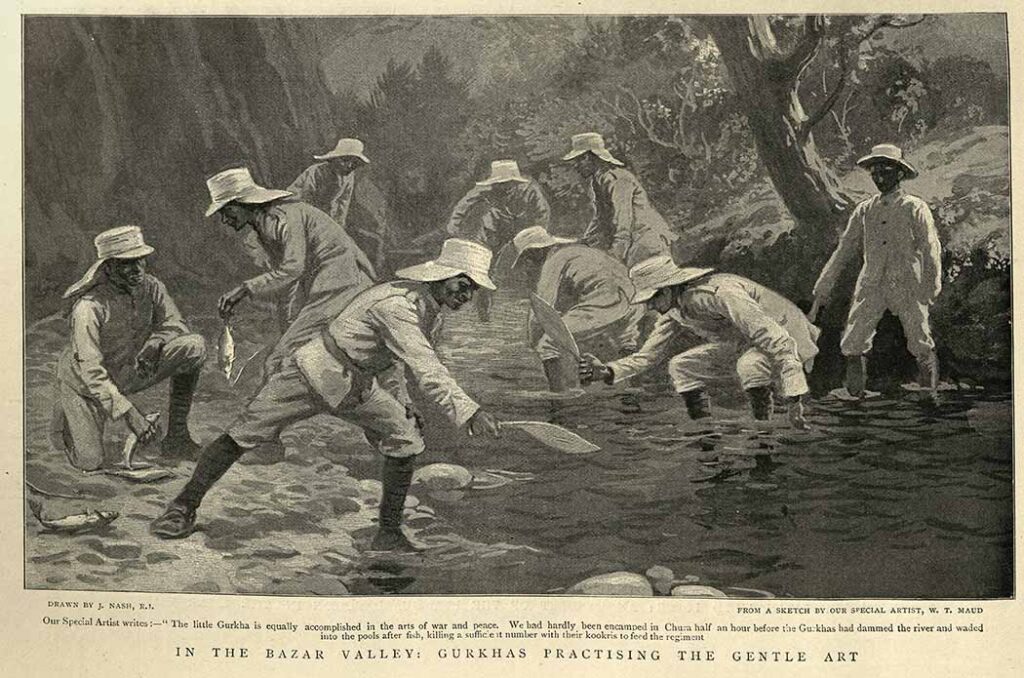

You can’t mention the kukri without mentioning the hand behind the blade: the Gurkhas. The history of the Gurkhas dates back several centuries to the small mountainous kingdom of Gorkha, located in what is now central Nepal. In the early 19th century, the British East India Company was expanding through the Indian subcontinent and faced challenges from local rulers and neighboring powers. The Gurkhas had a reputation for being a substantial military force in the region. So, the company began recruiting Gurkhas into its own army. The first Gurkha units were formed in 1815 and they quickly gained a reputation for bravery and loyalty.

Since the first Gurkha units were formed, they played a pivotal role in many conflicts and to this day remain an important part of the British Army. The Gurkhas fought for the British during the two World Wars, with Gurkha soldiers serving in various theaters of operations, including the Western Front, North Africa and Southeast Asia. About 200,000—virtually an entire male population—enlisted to fight in World War I. About 250,000 fought in World War II. In the two wars, 30,000 Gurkha troops were killed.

Continuing to serve with the British, they participated in the Falklands War in 1982, and have been involved in recent conflicts in Malaya, Borneo, Bosnia, Iraq—including the Gulf War—and Afghanistan. Soldiers that have served alongside the Gurkhas regard them with respect. The spine-chilling cry of “Ayo Gurkhali!”—“The Gurkhas are coming!”—has terrified countless enemies. The Gurkhas’ bravery and determination in battle earned them numerous honors and awards. In the two World Wars alone, they won nearly 5,000 medals for gallantry.

After the second World War, the British started to pull back from their colonial interests, allowing their various colonies to practice more independent self-governance. Even so, the British Army continued including the Gurkhas as an important part of their operations. Meanwhile, the kukri legend had no choice but to grow as it was made famous by the Gurkhas’ outstanding reputation for bravery and loyalty.

K-Tact Kukri Updates

The traditionally made kukri is a coveted piece in anyone’s collection. Condor Tool & Knife has updated the design with the use of modern materials to bring about a new tool with a pedigree. With the K-Tact Kukri Knife Army Green designed by Joe Flowers, the company remains loyal to the original shape but modified some materials and proportions.

Instead of using the wide variety of natural handle materials seen on kukris over the years, Condor opted for a green Micarta®. Micarta is much more stable, and for better grip Condor gives it a textured bead-blasted finish.

You may have heard how the blades of the originals were made from truck leaf springs. Truck leaf springs were made from such carbon steels as 5160 or 1095, or reasonable facsimiles. I often wonder about the truck leaf spring story. If you think about it, seeing as how the kukri also was used by villagers along with other patterns of knives to get work done, that means a lot of trucks would be losing their springs. Condor uses 1075 carbon steel with a bead-blasted finish for the K-Tact, which is named after Alan Kay, season one winner of History Channel’s Alone reality survival show.

Traditional kukris have a convex edge and are finished in a high polish. Condor convexes the K-Tact only part way up the blade and then leaves it flat. Blade thickness is .2 inch, thinner than most traditional models.

The average Nepalese villager’s kukri was made differently than the official Gurkha model. Possibly due to the time needed to make them and the lack of available steel, villager kukris had stick tangs. The Gurkha models have always been full tang and so is the K-Tact. Because of the thinner stock and the fact Condor took some weight off the blade with a stylized dip in the spine, the knife is livelier in the hand and feels more balanced.

Any of the traditional kukris I have held have had forward-heavy blades. They have a thick pommel plate the same thickness as that of the blade material. Having a thick pommel gives you a convenient hammer when needed and also enhances the knife’s balance.

K-Tact Kukri Versatility

One of the big keys to the kukri design is that it’s a great maker’s tool. It is not used for combat only. Among the recognized attributes of the Gurkha fighting units is their resourcefulness, and a large part of that is that the kukri lends itself to being a maker’s tool. Just the overall shape allows you to do many chores. It can act as a small draw knife due to the arched shape.

For the sheath, instead of the traditional water-buffalo-covered wood, Condor uses a molded Kydex with a drop-leg leather strap and a retention strap. Despite being a huge traditionalist at times, I have to say the modern sheath is a huge improvement. The fit is spot on and you get none of the Kydex-rattling syndrome.

If I had to voice a disappointment in the K-Tact, to be fair it would be more of a “I want my cake and eat it, too” complaint. On a traditional kukri you get an extra small knife and a steel that ride behind the blade next to your body in the same sheath. Though I don’t have much use for the sharpening steel—I carry other sharpeners—a secondary small blade is a key part to the maker’s aspect of the knife.

Yes, I know, I can carry another smaller knife, hence the “cake and eat it, too.” Having said that, there is still something about the knife presenting as a kit all in one housing. Keep in mind I am a father-and-son-knife-set collector. All I’m saying is, it would have been nice to have a matching small blade with it.

Use Before Buying

I must say I have enjoyed playing with this knife. It works well. Kukri-style knives aren’t for everyone, so do try and use one before you buy. Each knife style has its own little ins and outs. If all knives worked the same, what reason would enthusiasts have to collect multiples?

As a final thought, the K-Tact is a good, solid, dependable piece of kit and in the right hands can take you far. Who knows? You might discover that you just want a modern version of a legendary style. Made in El Salvador, it has an MSRP of $162.84.

Check Out More Buyer’s Guides:

- Best Kukri Knife Options

- Best EDC Fixed Blade Knife Options

- Best Bushcraft Knife: When Steel Meets The Woods

- Best Neck Knife: Options To Yoke Up With

- Best Tomahawks: Our Top Hawks For Backwoods To Battlefields

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

BLADE’s annual Knife Guide Issue features the newest knives and sharpeners, plus knife and axe reviews, knife sheaths, kit knives and a Knife Industry Directory.Get your FREE digital PDF instant download of the annual Knife Guide. No, really! We will email it to you right now when you subscribe to the BLADE email newsletter.

I have two remaining of the 8 or 9 Nepalese kukris after giving the others to family and friends as gifts. The 3 Condors went to family as well. Do I like one model over another. No. Not really. I collect based on usage and find that all knives have their purpose. The Condors are just as nice to own as the Nepalese. My problem seems to be that one can never own enough knives.