Off to See a Relic

On a warm and sunny Saturday morning in August 2010, my friend and fellow BLADE Magazine Cutlery Hall-Of-Fame© member, B.R. Hughes, and I left the American Bladesmith Society All-Forged Knife Expo at the Gunter Hotel in San Antonio, Texas, on foot to hike the quarter mile to the Alamo. Our mission was to see the coffin-handle bowie knife relic in the Sea of Mud exhibit at the Alamo gift shop. The relic had been unearthed years earlier by Dr. Gregg J. Dimmick, author of the highly acclaimed book, Sea of Mud.

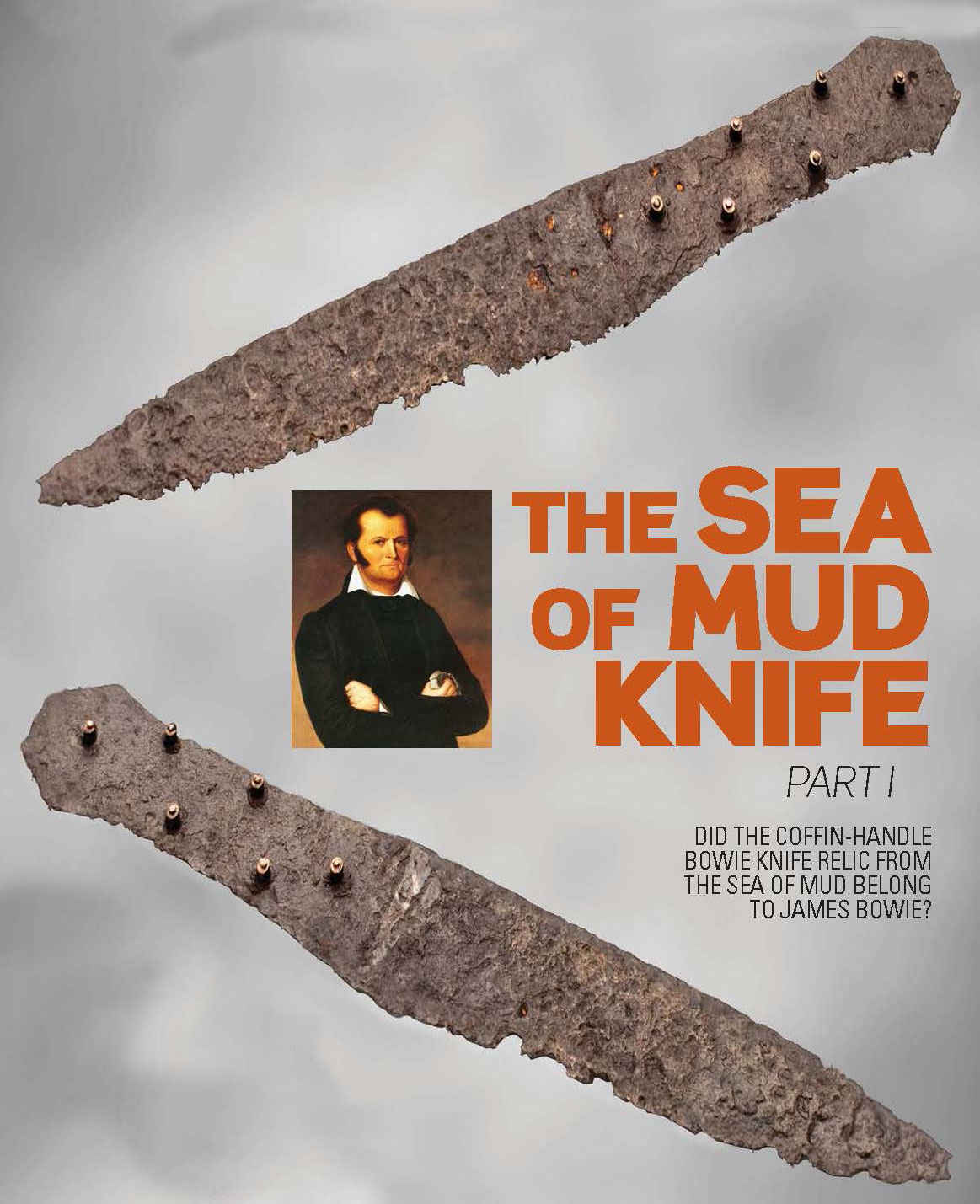

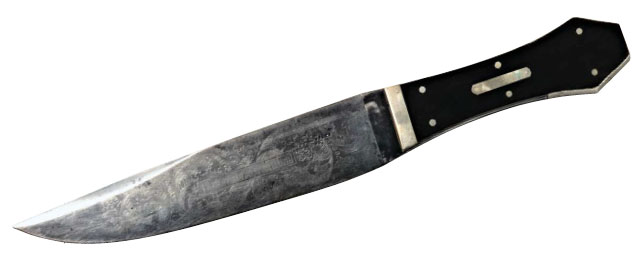

Made during Cutlery Hall-Of-Famer James Bowie’s lifetime, the relic may have been used in the defense of the Alamo, which fell on March 6, 1836. I had not seen the relic but ABS master smith Greg Neely had sent me a picture he had taken a few years earlier. Below the relic was a placard with the following inscription: BOWIE KNIFE.

The relic is iron and has brass connectors in the handle. There are two small strips of decorated silver on the blade near the handle on both sides. A very small amount of the silver can still be seen. The relic had been cleaned by electrolysis. The relic is interesting due to its similarity to Bowie No. 1, the coffin-handle bowie attributed to James Black of Washington, Arkansas.

Identification

I had learned early on that you cannot identify or verify an authentic bowie knife unless you hold it and see it—in this case, eyeball to rusty metal. From Greg’s picture I could not be sure how big the relic was. However, from the shape of the blade and coffin handle, along with the pin pattern and the studs in the handle and the silver overlays on the blade in front of the handle, I suspected that it was made by Black circa 1831-1838, in Washington, Hempstead County, Arkansas Territory.

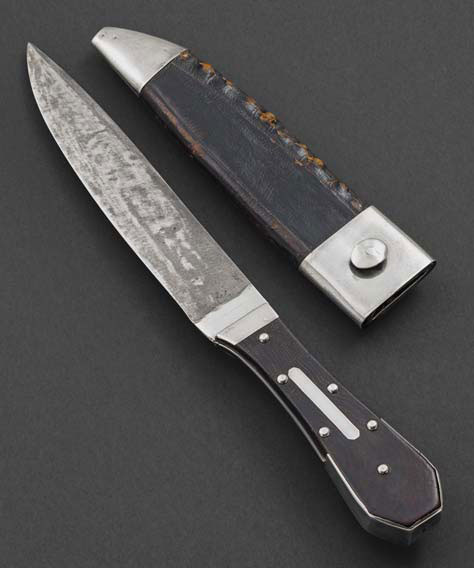

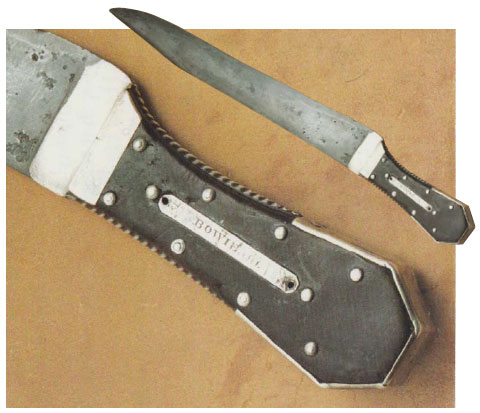

From my bowie knife research, I have concluded that Black originated the coffin-handle style that became one of the most popular of bowie knives. A Black knife did not have a guard. Makers in America and Sheffield, England, incorporated guards into the design.

Two of those that made coffin-handle bowies with the silver overlays on the ricasso area were Marks & Rees of Cincinnati, Ohio, and Crown Alpha of Sheffield for Gravely & Wreaks in New York. Marks & Rees was the first to advertise bowie knives for sale, and the Crown Alpha Bowie had Arkansas Toothpick elaborately etched on the blade.

As you can see in the fourth image up, the small Carrigan knife made by Black more closely resembles the relic than the Marks & Rees (above) or the Crown Alpha knives (above Marks & Rees). Also, you can see that Bowie No. 1 (third image up) does not have the same pin pattern as the relic but has many of the same characteristics of the Carrigan. Bowie No. 1 has a bigger handle and much longer blade (13.5 inches).

“I Could Tell He Made It”

B.R. and I arrived at the Alamo gift shop after paying homage to the fallen by visiting the Alamo Chapel. Boy, was the Sea of Mud exhibit crowded! We had to stand in line.

There was the relic and I could tell Black made it. I could tell from the studs that at one time had secured wood scales to the full tang. To my knowledge, Black was the only person to use this technique. The blade lengths of the relic and seven known silver-mounted Black-made, coffin-handle bowies are about 6 inches, with handle lengths of about 4 inches. The placement of the six pins looks as if Black used the same pattern to drill the holes in the tang of each knife.

The relic had been on or in the ground for at least 160 years, but where were the top-and-bottom silver tang wraps? Where were the two silver wraps around the front of the wood scales? Where were the two silver escutcheon plates? Where was the silver pommel wrap, and where were the twelve domed silver washers that secured the scales to the tang? And where were the walnut scales?

If the relic had been dropped by accident or lost, some of the silver mountings should have been part of the artifact, since silver is a noble metal and difficult to corrode. The wood may have deteriorated or rotted away, taking some of the attached silver mounts with it.

Lost to Time

I contacted Dr. Dimmick and asked if he found any evidence of silver or wood in the soil adjacent to the artifact. He said nothing was found in the proximity of the relic but that a brass pommel cap was found at the same site, though not near the relic.

The relic could have been lost and over time lost the silver mountings. Or, a Mexican soldier or camp follower who needed money and valued the relic only for the silver he or she could remove from it may have retrieved the relic, and the relic was not lost but discarded after the silver fittings and wooden scales were removed. Silver could not be removed from the blade. It was soldered with tin.

A Mexican officer with some wealth may have kept the knife, especially if it had a coin-silver-mounted sheath.

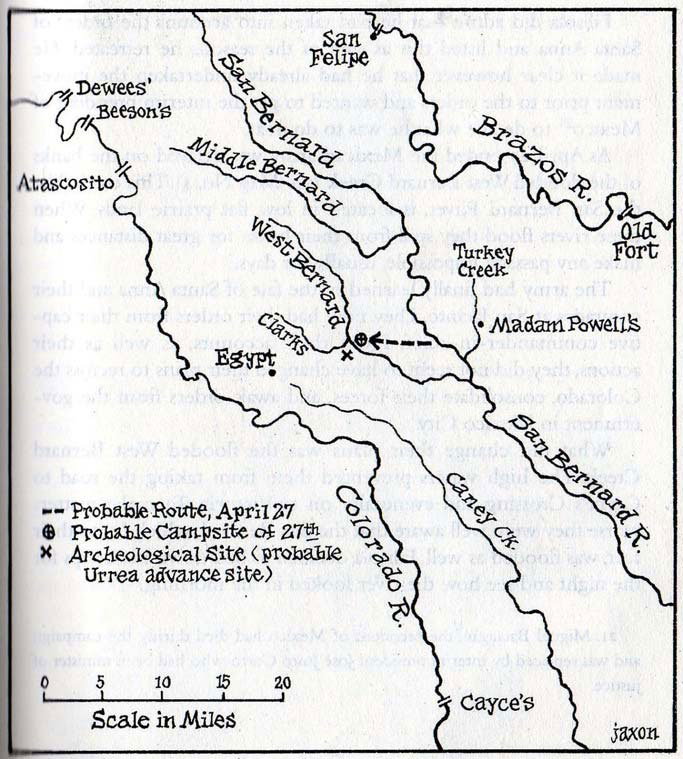

The coffin-handle bowie knife relic was found on the west side of the West Bernard River below the mouth of Clarks Creek in Wharton County, not far from Hungerford, Texas. The West Bernard River was crossed from west to east by Mexican Gen. José de Urrea’s division on April 20, 1836, the day before the Battle of San Jacinto.

According to Dr. Dimmick, “Based on the distances recorded by the San Luis Battalion on April 19, it is believed that this site was not a campsite. The campsite of April 19 was probably near present-day Spanish Camp, Texas. If this is correct, it is theorized that the site discovered on the West Bernard is where Urrea and his division crossed the river during their advance. It is possible that these artifacts were discarded at the site as the units awaited their turn to cross. The artifacts from this site are consistent with the above theory.”

Gen. Urrea’s division was not at the Alamo. However, then-Col. Juan Morales and his men were, and they reinforced Urrea after the fall of the Alamo. (It was about 100 men under Morales’ direction who attacked the Low Barracks where James Bowie was killed during the Alamo battle.)

Urrea subsequently led his division along the coast from Matamoros to Goliad and Victoria. His primary opposition led by Col. James W. Fannin consisted of volunteer units from the United States.

These troops took steamboats down the Mississippi River to New Orleans and went over land or by sea to Texas. The Matamoros Expedition led by Col. Francis Johnson and Dr. James Grant consisted of the New Orleans Greys and the Mobile Greys. None of these troops had been through Washington, Arkansas, or heard of James Black.

So, was the coffin-handle bowie relic owned by a defender at the Alamo? And if so, how did it get from Washington, Arkansas, Territory to the Alamo, and from the Alamo to the West bank of the West Bernard River? Was this James Bowie’s knife?

Love Knife History? Get This BLADE Download

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

BLADE’s annual Knife Guide Issue features the newest knives and sharpeners, plus knife and axe reviews, knife sheaths, kit knives and a Knife Industry Directory.Get your FREE digital PDF instant download of the annual Knife Guide. No, really! We will email it to you right now when you subscribe to the BLADE email newsletter.

Nice article. Historical investigation at its finest !