I’m going to walk you step by step through making a bowie from a common farrier’s rasp, as simply as possible, with a few tips to save time and improve the finished blade as we go. It is a simple bowie-style camp knife useful for all sorts of tasks.

1) Pattern Sketch

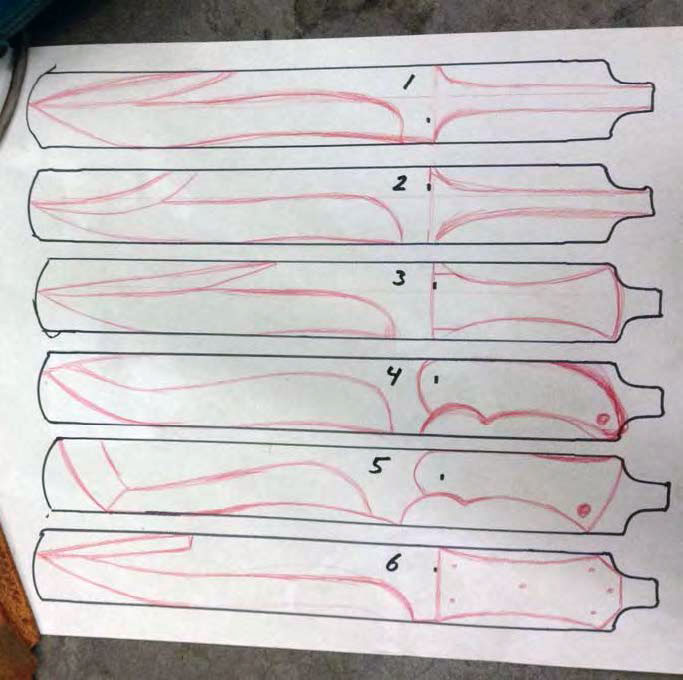

The first thing you need to do is decide on a style that suits your needs and your purpose. I find that visual aids are the easiest way to get the results I’m after, so I often do several sketches and drawings to decide what I’m trying to accomplish.

For this I traced the rasp multiple times on a large sheet of paper so I could compare each style side by side and see what works and what doesn’t, as well as what the maximum potential of my material was. I decided on blade shape #4 with handle shape #5. The combo should be a good general chopper and comfortable in the hand.

By visualizing this way I can mix and match infinitely. Don’t be afraid to get creative, especially when using recycled and often-free materials. This is a chance to express yourself and your vision in steel.

2) Annealing

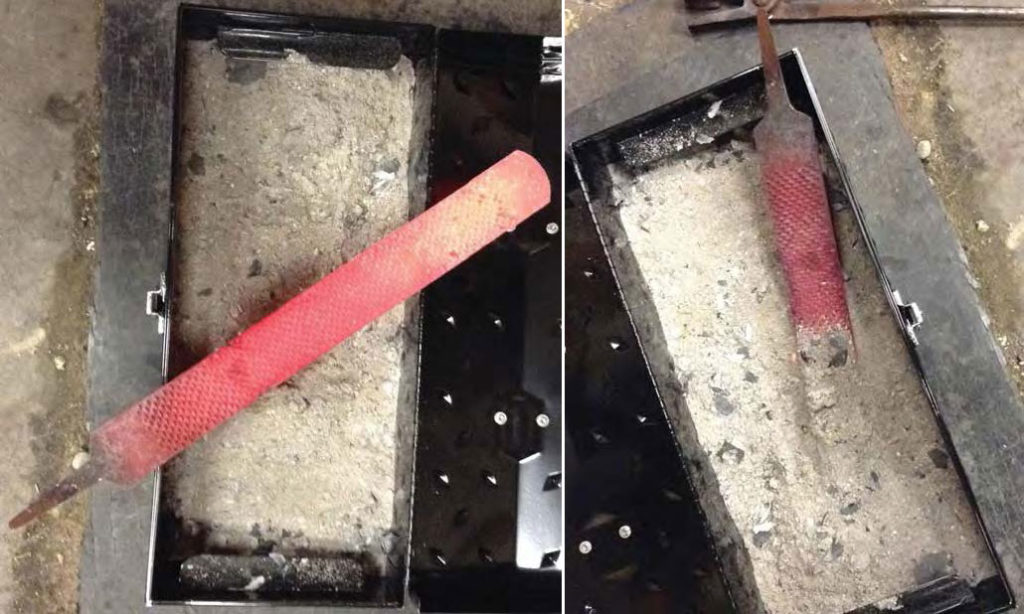

Now you have a design in mind, but, before you can achieve bowie knife greatness, you must anneal the rasp so it can be shaped, drilled and ground more easily.

It is certainly possible to make a rasp or file knife without annealing, but great care must be taken not to get the steel too hot and ruin the temper. Moreover, the high hardness of the file in its current state means a blade made this way would be very brittle and prone to breaking under hard-use conditions.

If you have access to a heat-treating oven, by all means use it to anneal your steel. This is a very simple and basic build, so I’ll be heating the rasp to nonmagnetic and then burying it in a simple metal toolbox filled with clean wood ash. Burying it insulates the steel, allowing it to cool very slowly. The slow cooling softens the steel so it’s easier to work.

Vermiculite is also great for this step if you don’t have access to wood ash. Vermiculite can be purchased at most garden centers and insulates very well. It will take several hours for the rasp to cool. Don’t rush it! It will be well worth it once you start filing, drilling and grinding.

3) Design Transfer

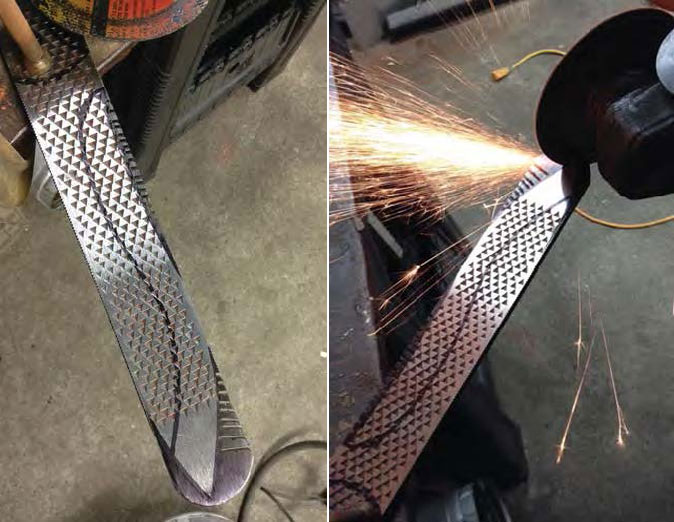

The rasp has cooled and it’s time to go to work. The first step is to grind the teeth off both sides. This leaves a nice, flat surface to work with but the memory of the rasp is left behind, which gives the knife a distinctive, rugged look.

An angle grinder will work great for this task, but any number of basic tools will suffice. Use whatever is readily available to you. Once the teeth are cleaned off , transfer the blade design to the rasp. Cutting out the pattern and over spraying it with black paint works very well.

However, since this design is fairly simple, I drew it out with a permanent marker.

4) Notched & Cleaned Up

Now you can start cutting out the profile. Notching out the shape with a hacksaw or cutting wheel will make the job quite a bit easier. I find that removing small pieces of metal is easier then trying to make large cuts.

After the bulk of the steel has been removed, the final profile can be shaped out with files or an angle grinder.

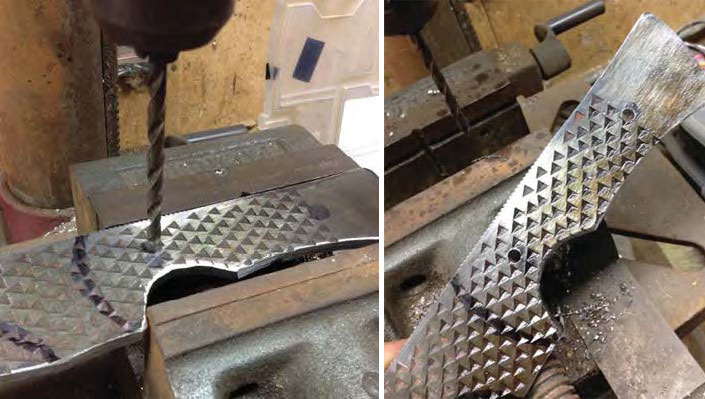

5) Drilling Pins

The blade is starting to take shape. Now is a good time to consider what handle material is best for your creation.

There’s no wrong choice. With the seemingly limitless options available today, you can truly express yourself from mild to wild. If you’re feeling traditional you can go with antler or perhaps stacked leather.

If you want to go more cutting edge, there are hybrid burl blocks with every color resin in the rainbow. Shredded money and eggshells are even finding their way into knife handles these days.

I’m going more traditional, so now is the time to drill a couple of holes for pins. I’m going to use brass bolts as pins. They are inexpensive and can be bought at any hardware store. The threads add an extra mechanical bond when they are epoxied into place, and also act as built-in clamping devices to ensure a solid, tight fit-up when the scales are applied.

6) Grind the Bevels

With the profile cleaned up and all necessary holes drilled, it’s time to start grinding in the rough blade bevels in order to get your blade ready for hardening.

The trusty 4-inch angle grinder goes to work again, though a bench-top grinder or even a good, sharp file will get the job done. The goal here is simply to remove the bulk of the metal on the sides of the blade evenly so there is less work to do after hardening.

Don’t grind all the way to sharp at this point! Leave the edge about the thickness of a penny—this will protect the steel that will become your cutting edge from overheating and decarburization, helping to ensure your finished knife will live up to its maximum potential.

Once the bevels are roughed in, finish up with sandpaper or a flap disc to 220 grit. Be sure to remove any deep, heavy scratches, as these could lead to cracks during hardening.

7) Heating and Quenching

Now you’re ready to harden some steel! I’m going to use a forge to heat the blade to nonmagnetic—aka the critical temperature—though a torch works equally well.

Slowly bring the blade up to temperature and check it oft en with a magnet. When nonmagnetic is reached, edge quench to harden the cutting edge, and leave the spine slightly softer for additional strength and toughness.

Submerge the blade in the quench oil once all the color has left the blade and it goes to black. Allow the blade to cool to room temperature in oil. This will take an hour or so.

A variety of things will work as quench oil and everyone has a favorite. Depending on the types of steel used, I’ve had good luck with canola oil, ATF transmission fluid and mineral oil. I quenched my blade in Texaco type A.

WARNING! Mixing hot steel with oil can and will cause a fire! Be sure to take appropriate safety precautions. A well-ventilated space free of other flammable materials, as well as personal protective gear and a fire extinguisher, are musts!

8) Check for Hardening

soap and warm water.

Once the blade has cooled, remove it from the oil and clean it off . Brake cleaner works well for this, as well as simple dish soap and warm water. If the hardening was successful, you should see an area of clean steel on the cutting edge where the carbon scale has popped off the blade.

A second simple and easy way to check for a hardened blade is with a fresh, sharp file. Run the file over the knife’s cutting edge. The file should skate easily and not bite into the edge. If this is the case, you are ready to temper the blade.

9) Tempering

Tempering is a fairly simple process. Basically, in order to reduce brittleness and increase toughness, tempering is heating the blade to a lower temperature than you did in the annealing step.

Again, if you have access to a heat-treating oven, by all means use it. However, a toaster oven or basic household oven will work just as well. Oven temperatures vary greatly—especially toaster ovens—since they lack heavy-duty insulation. This means the exact temperature you need to use will vary as well.

I start by putting my blade in the oven for an hour at 375°F. As the steel heats it oxidizes, and the clean portion changes color. This is a simple, basic heat treatment and temper, so the color change is your indicator rather than an exact temperature.

As the heat rises the color goes from a bright gold to a shade of bronze straw, then a light purple to a blue on its way to a dark blue/almost black. The dark bronze to purple is your goal. The blade should be hard enough to hold a good edge but soft enough to not chip or break during use.

I did three one-hour cycles, each 25°F hotter according to my oven, and 425°F was the temperature that gave me the desired result. A simple trick to get a more even heat in a regular household oven is to put a sheet pan on the bottom rack.This holds heat closer to the element and keeps the temperature fluctuations to a minimum.

10) Finishing and Final Edge

Now you have a hardened and tempered blade ready for finishing and a final edge.

You need to remove only a small amount of steel to get down to the final edge. Don’t rush at this point! Go slowly to keep from getting the steel too hot and ruining all your hard work up to now. As long as the steel stays bright and shiny you will be fine. Any discoloration at this stage means overheating and the risk of losing the blade temper.

You also are working down to the final, finished and sharp edge. Stitches aren’t cheap! Be aware of where your fingers are.

Some light grinding or fi ling as in the previous steps will bring your bevels down to the finished edge. Polish to at least 220 grit. A higher-grit polish will look more finished, as well as be less prone to rust, and provide smoother, more fluid cuts.

Once you get to 220, it’s time to apply an edge and see how you did. Some simple test cutting and chopping will tell you if you need to change anything, such as the thickness of your cutting edge or if you need to re-temper perhaps a few degrees hotter. Use the materials you originally planned on cutting with your new bowie to decide this.

For example, since the blade primarily will be a camp knife, simple tests such as splitting kindling, cutting rope and twine, and making the all-important hotdog stick will tell you what you need to know.

Time to Make the Handle

Click here to read how to make a handle for this knife.

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

NEXT STEP: Download Your Free KNIFE GUIDE Issue of BLADE Magazine

BLADE’s annual Knife Guide Issue features the newest knives and sharpeners, plus knife and axe reviews, knife sheaths, kit knives and a Knife Industry Directory.Get your FREE digital PDF instant download of the annual Knife Guide. No, really! We will email it to you right now when you subscribe to the BLADE email newsletter.