Bigger and better than ever, BLADE Show Texas has something to offer everyone deep in the heart of the Lone Star State.

A switch to the plush Fort Worth Convention Center, an expanded roster of international and domestic custom and factory knifemakers and much more promise to make BLADE Show Texas one for the record books March 18-19 in Fort Worth.

Formerly known as the International Custom Cutlery Exposition (ICCE) and held last year at the Fort Worth Stockyards, the new name of BLADE Show Texas and the new venue are all part of the event’s continued revamping under the umbrella of the world’s largest and most important knife show operation, the BLADE Show, the latter which will be June 4-6 at the Cobb Galleria Centre in Atlanta.

But first thing first—and that thing is BLADE Show Texas.

Approximately 300 exhibitors will be on hand to display their hottest knives, knifemaking supplies and more. Among those exhibitors are members of both The Knifemakers’ Guild, the American Bladesmith Society and many other unaffiliated makers as well. Also exhibiting will be a number of cowboy artisans to show off their creative works in spurs, bits and similar gear in a special section of the Exhibit Hall E-F called Cowboy Alley. All will gather in the expansive Fort Worth Convention Center in the heart of downtown Fort Worth. Spanning 14 city blocks of the city’s central business district, the convention center is surrounded by four-star hotels, restaurants, shops, galleries and assorted performance venues, with free transportation provided throughout the downtown area via Molly the Trolley.

Helping make the show a reality are its sponsors, which include Smoky Mountain Knife Works, WE Knife Co., Civivi, Hogue Knives, New Jersey Steel Baron and The Blade Bar.

Get Your BLADE Show Texas Tickets Here!

Top Exhibitors

Last year’s show was one of the first major knife events to return after the pandemic had caused a number of other shows to cancel, and people who both attended and exhibited gave it rave reviews. Many makers sold out and many who didn’t sell out didn’t miss by much. Bubba Crouch, who, along with many other members of the South Texas Cartel of custom slip joint makers returns this year, said it was the best-attended show he’d been to since BLADE Show 2019. “There was a lot of money in the room and a lot of veteran-type collectors,” he observed. “I brought three or four customers who’d never been to a knife show and they were overwhelmed with all the talent.”

This year’s array of talented artisans promises to be even better. An incomplete but representative sample of domestic and international exhibitors in assorted categories includes:

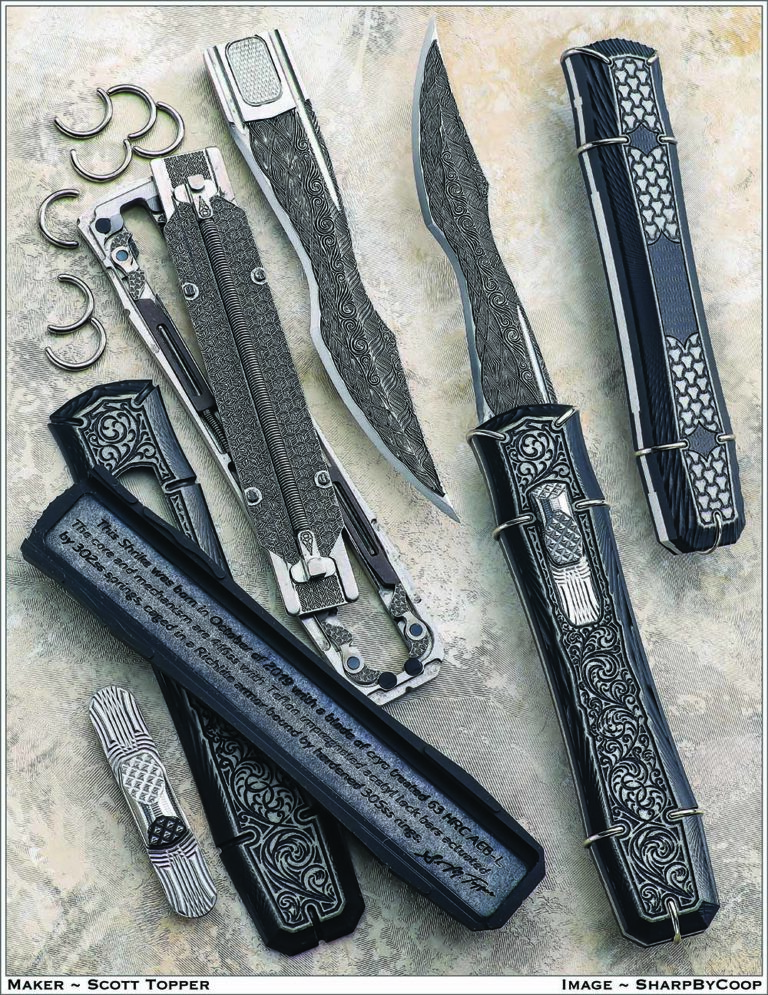

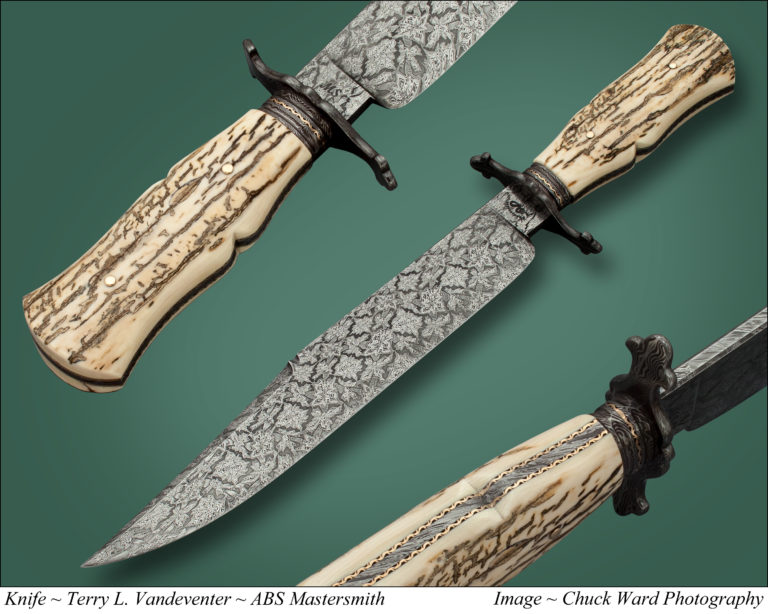

- Bladesmiths: Bill Burke; Brion Tomberlin; Bruce Bump; Murray Carter; Jerry Fisk; Harvey Dean; Jason Fry; South Africa’s Henning Wilkinson; J.W. Randall; James Cook; James Rodebaugh; Jason Knight; Jean Louis Regel of France; Josh Fisher; John Horrigan; Kelly Vermeer Vella; Lin Rhea; Mike Tyre; Rick Dunkerley; Steve Schwarzer; Scott Gallagher; Shane Taylor; Shawn Ellis; Shayne Carter; Belgium’s Veronique Laurent; and Tommy Gann;

- Slip joint makers: Bill Ruple, Chris Sharp, Bubba Crouch, Burt Flanagan, P.H. Jacob, Enrique Pena, Tom Ploppert, Stanley Buzek, Luke Swenson, Tim Robertson, Tobin Hill and Trae Gaenzel;

- Assorted other top makers: Allen Elishewitz, Brian Fellhoelter, Peter Carey, Dennis Friedly, Johnny Stout, Tom Krein, Lee Williams, Jeremy Marsh, Princeton Wong, Brian Nadeau, T.R. Overeynder, Todd Begg, Scorpion 6 Knives and Michael Zieba;

- Factory knife/accessory companies: Fox Knives, Heretic Knives, Hogue Knives, KeyBar, Liong Mah Designs, Microtech, Pro-Tech, Reate, RMJ Tactical, Squid Industries, TOPS Knives, White River Knife & Tool, WE Knife/Civivi and Wicked Edge Precision Sharpeners; and;

- Knifemaking/knife equipment suppliers: Culpepper & Co., Damasteel, Evenheat Kiln, Fine Turnage Productions, Jantz Supply, Knife & Gun Finishing Supplies, Moen Tooling, Nichols Damascus, Paragon Industries, Pops Knife Supply, Rowe’s Leather, Vegas Forge Damascus and Wuertz Machine Works.

BLADE Show Texas Awards

The knife awards for the Texas BLADE Show have been especially tailored this year to address the specialties of the exhibiting makers. As a result, the awards in the custom category will be Best EDC, Best Slip Joint, Best Kitchen Knife, Best Fixed Blade, Best Folder, Best Damascus, Best Art Knife and Best in Show. Each winner will be judged in terms of how well it fits the category, quality design, construction and materials, fit and finish, line and flow, and the other intangibles that identify most top knives.

The knife awards in the factory category will be Best EDC, Best Fixed Blade, Best Folder and Best in Show, with each winner judged in the same terms as those used to rate the custom winners as outlined in the preceding paragraph.

Demos

The BLADE Show franchise is renowned for its cutting-edge demos, and those for BLADE Show Texas maintain that tradition. All are free of charge to show attendees. On Friday those demos will include:

12 p.m., Grinding Seminar, Room 104: Using only four abrasive belts on his Moen Tooling Platen and grinding fixture, Jerry Moen of Moen Tooling will show you how to apply a bevel grind in a 2,000-grit finish.

2 p.m., Fundamentals of Inlay, Room 104: Award-winning bit-and-spur maker Wilson Capron will demonstrate several different inlay styles and techniques and the tools to do them with, styles and techniques that can be applied to assorted media;

3 p.m., How to Make the X-Rhea Knife, Room 104: ABS master smith Lin Rhea will outline the details that go into the making of his X-Rhea knife, including variations on a theme, how the design came to be, how to forge it and more.

All Day, Free Knife Sharpening and Hands-On Demo, the Mobile Forge: Joe Maynard of Primitive Grind will provide hands-on demos and free knife sharpening.

Saturday’s demos will kick off at 10:30 a.m. in Room 104 with a repeat rendition of Jerry Moen’s Grinding Seminar. In addition, Joe Maynard will conduct his All-Day Free Knife Sharpening and Hands-On Demo in the Mobile Forge. The day’s other seminars will include:

12 p.m., How to Make a Single Blade Trapper, Room 104: Award-winning makers Luke Swenson and Bill Ruple and other members of the South Texas Cartel will show you how it’s done based on Swenson’s video tutorial “Slipjoints with Luke Swenson.”

1:30 p.m., Leather Sheath Making Demo, Room 104: Joey Dello Russo of Imperial Leather Works will give a complete rundown on how to make a sheath, including measuring the blade, leather thickness, welt dimensions, belt loop location, and sizing, laying out and drawing the pattern.

Texas Gun Experience

Blade Show Texas and Texas Gun Experience have teamed up to provide a night of hands-on experience in a safe and managed environment. Show attendees are invited to a private demo event on Saturday evening from 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. Only those that have a BLADE Show Texas wristband will be eligible to attend to the TGE event and are eligible to win the following giveaways:

- Springfield Armory’s Hellcat Giveaway

- Springfield Armory’s Hellion Bullpup Giveaway

- Ammo from AMMO, Inc

- Ammo from Global Ordnance

- Possible Ear Protection from AXIL Earbud Hearing Protection

- RifleScope from Accufire

- And other products…

For more information on the show, pick up your special show program at the event itself or visit bladeshowtexas.com. For more information on the Fort Worth Convention Center, visit fortworth.com/convention-center.