“A Knife For Those Who Saved Alaska”

BY ANDY SHARPE

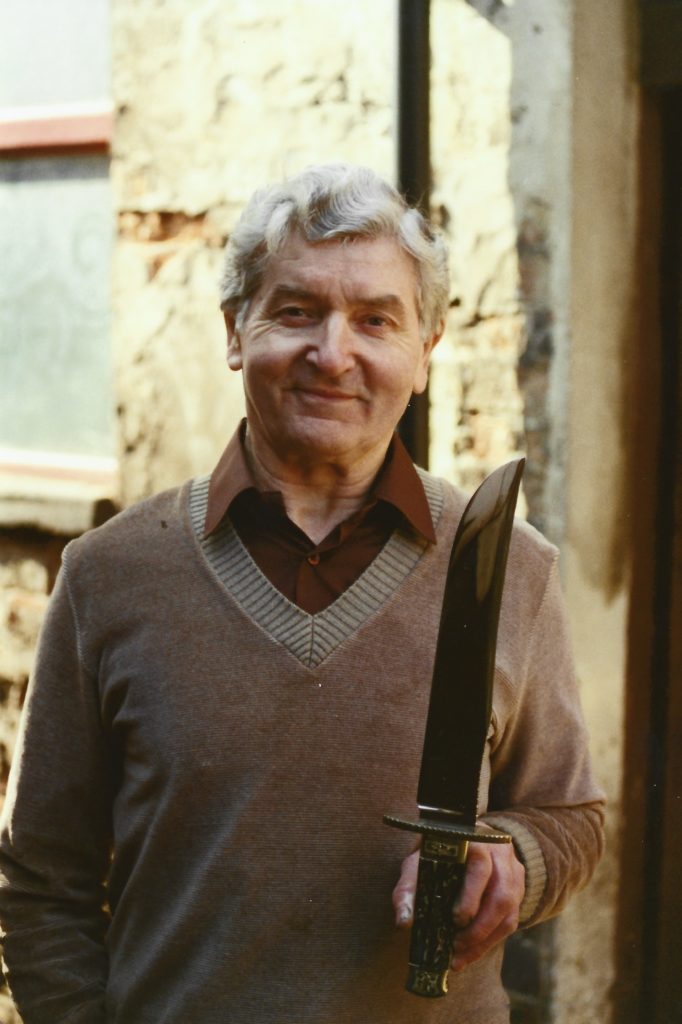

Herb Drury was my wife’s uncle, a World War II veteran and a friend. He passed away in 2007. I miss him and the discussions we used to have. I guess I was one of only a couple of people he talked to about his time in World War II. He served in the Pacific Theater on Attu Island in Alaska and in the Philippines. The thing I noticed was he always went to Attu. For some reason the place haunted him and was still fresh in his memory after 60 years.

Uncle Herb was a tall, thin man with mild mannerisms. As he told me about the battle of Attu, it was hard to picture him there. It was even harder to visualize this kind and gentle man hurting anyone.

He was trained for desert fighting in Africa. As part of the U.S. 7th Infantry Division, he was sent to Attu Island. They had no winter gear. The Army thought the heavy gear would slow the men down. Even though it was May, the arctic weather was below freezing. He told me of men burning the wooden stocks of their rifles trying to stay warm. He said it was a pretty easy landing and they thought maybe the Japanese had left. It wasn’t long before they discovered the Japanese were still there.

He talked about the banzai attack. He could not comprehend that the Japanese were so willing to die. He said that after the attack, “We walked around and looked at the damage. The men in the hospital tent had been killed in their beds.” He told me the Japanese soldiers, before allowing themselves to be taken prisoner, would gather in a circle and hold grenades to their chest to commit suicide. He said he came upon a wounded Japanese soldier. “I just emptied my gun into him,” he recalled. It was hard to picture this soft-spoken, gentle man doing this.

After he passed away I thought of him often, and when I thought of him I thought of Attu. I wanted to do something in his memory. As a knifemaker it only made sense that I make a knife. It had to be special. Then it came to me: Use artifacts from Attu. And so the research began.

I searched the Internet for weeks trying to find all I could about Attu Island. I discovered that the only people on the island were 22 members of the U.S. Coast Guard. I did find an article about the Coast Guard’s Attu Station that listed the phone numbers for the commander. I called the number and I talked with Commander Robert Coyle for about an hour. He told me he had just what I needed—an exploded artillery shell and assorted shell casings that had been found on the Coast Guard station. Problem was, no items could be removed from the island. The island is a National Historic Landmark and game preserve with a no-stone-turned policy and is under the control of the Alaska Fish and Game Department. I would need the department’s permission to remove the artifacts. He also gave me the name and contact information of other informed sources.

After three months of paperwork and waiting, I received permission to remove the artifacts from the island, with the stipulation that only one knife would be made and all the remaining materials be returned to Attu. I could receive items found only on the inside of the boundaries of the Coast Guard station. Commander Coyle boxed up the items and shipped them to me.

When the box arrived I was in awe. This was not just a bunch of scrap metal; this was a box of history. These are possibly the only documented artifacts from Attu Island in private hands:

PROJECT ATTU

I really began to start doubting my skills as a knifemaker. I was on the Knife Network Website and posted my story. ABS journeyman smith Chuck Richards expressed a great desire to be part of the project.

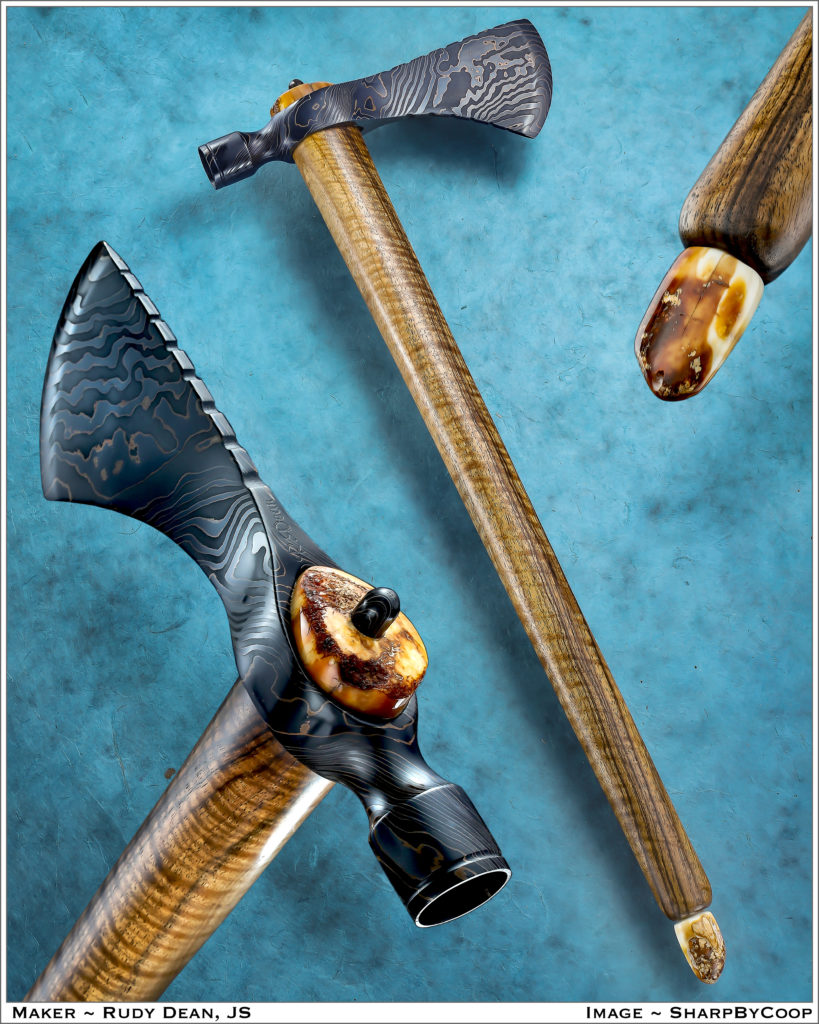

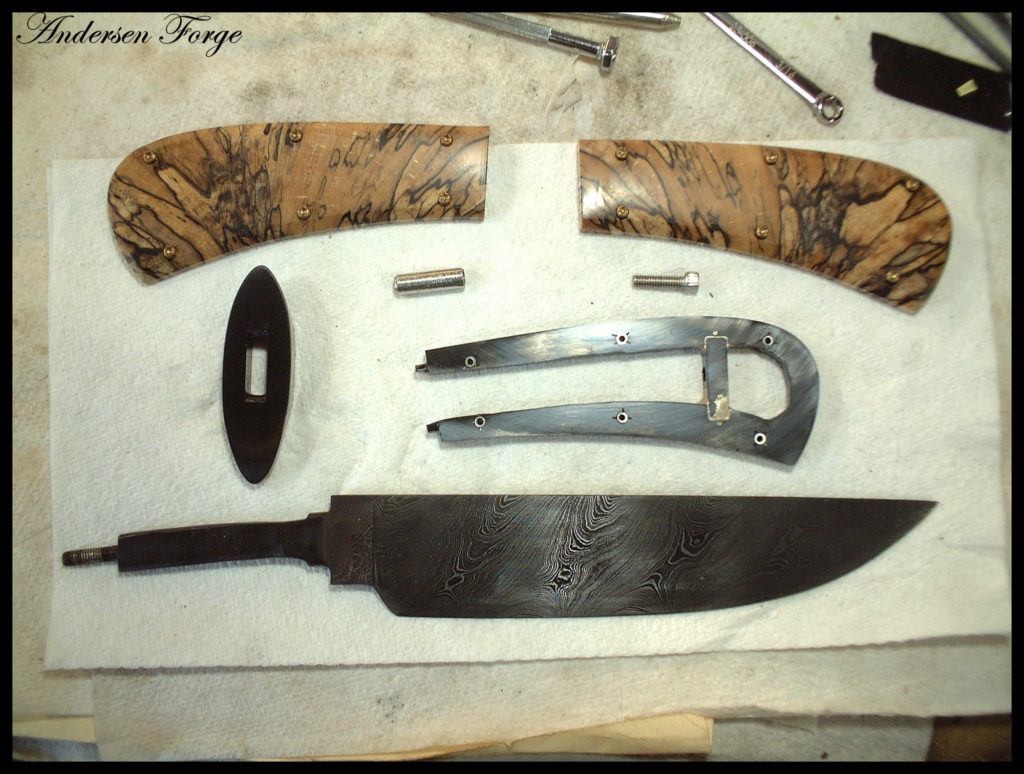

Chuck and I decided to collaborate on a simple knife design. He did his magic—a 9-inch bowie-style fighter of 575-layer ladder-pattern damascus. He forged the steel from an exploded artillery shell, a piece of spring from an abandoned truck on Attu and some 15n20 for contrast. The steel had a lot of waste due to micro cracks in the shell and corrosion from 60-plus years of exposure to the Alaskan weather.

We discussed the project and the weird feeling we would get while working with these materials. To make a knife is one thing—to make one from materials that cannot be replaced and if we messed it up it could not be redone is another. I think Chuck’s stress level maxed out. I cannot say enough about the artistry he brought to the project.

Now the knife was in my hands. How could I do justice to the beautiful blade? “Keep it simple” kept running through my brain. I decided on a basic flat guard made from a piece of the artillery shell. I had several M1 shell casings marked “42” for 1942—the military dates its ammunition—from Attu Island. I cut the base off the shells and set them in the front of the guard.

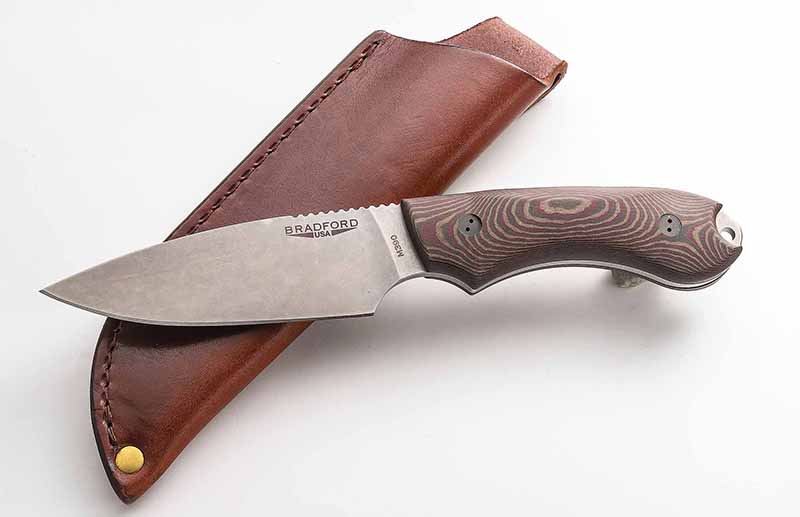

Above: Keeping it simple, Sharpe made the basic flat guard from a piece of an Attu artillery shell. He cut the base off two M1 shells the military had marked “42” for 1942 and set them in the front of the guard. (SharpByCoop.com knife photo)

The handle was easy. I had an ancient ivory walrus tusk I bought in Alaska in the mid-1970s. I never knew why I had kept it all these years but now I did. This is where it belonged. I made the ferrule and buttcap from pieces of artillery shell and cut the tusk to fill the void. I kept the tusk’s natural shape as much as possible.

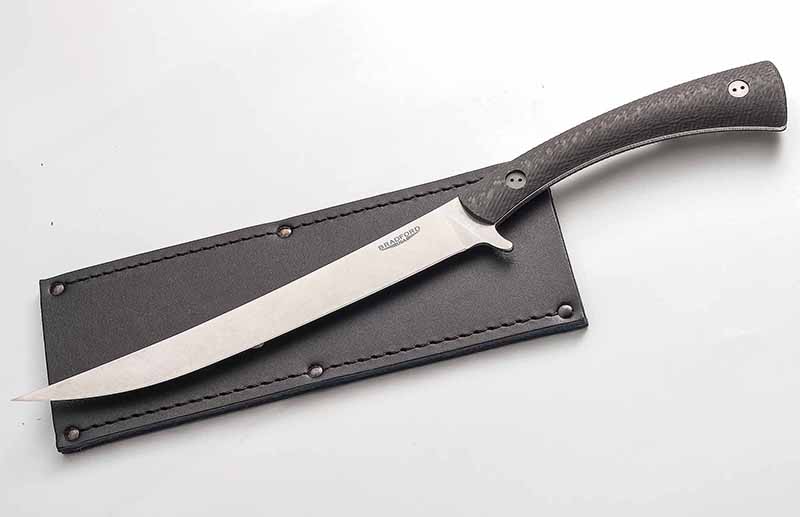

I took the M1 shells I had cut the base from and melted down the brass. I did a sand cast of Attu Island from the brass and used it as the centerpiece for the buttcap. A light etching for character and I was done.

Above: Sharpe did a sand cast of Attu Island from the brass melted down from the M1 shells and used it as the centerpiece for the buttcap.

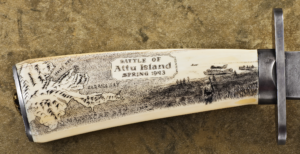

The knife was finished but it needed something. I contacted Richard (Hutch) Hutchings. He volunteered to scrimshaw the handle. Hutch’s work is amazing. While doing the Attu knife he was commissioned to do the scrimshaw for BLADE Magazine Cutlery Hall-Of-Fame© member Gil Hibben on the knives for The Expendables movie and all the residual work that came from that project. In addition, around the same time Hutch had a fire in his shop that destroyed a lot of his studio. Fortunately, he had locked all the knives he was working on in a fireproof safe. With all the setbacks the scrimshaw took over a year.

Jim Cooper of SharpByCoop.com volunteered to do a photo shoot of the knife. His work really brought out the knife’s details:

Allen Hutton donated his time and wood skills to make the display stand. He used the wood shipped from Alaska and California to build the structures to sustain the men fighting on Attu. (There are no trees on Attu Island.) His work is simply amazing.

They decided to raffle the knife off with 100 percent of the proceeds going to the World War II Memorial Fund. We donated the funds not from those of us who worked on the project but on behalf of Herbert Reginald Drury—Uncle Herb—and all the men who fought and those who died on this all but forgotten Island.

More on the Battle of Attu

The westernmost and largest island in the Near Island group of the Aleutian Islands of Alaska, Attu was the site of the only World War II land battle fought on an incorporated U.S. territory.

Japanese forces occupied Attu, home to a few native Aleuts, in June 1942. On May 11, 1943, a U.S. invasion force that included scouts recruited from Alaska nicknamed Castner’s Cutthroats set out to recapture the island. Frigid weather seriously hampered the invasion, with many GIs suffering frostbite. Rather than contest the landing, the Japanese dug in on the island’s high ground. Heavy fighting resulted in 3,929 U.S. casualties, including 580 killed.

On May 29, the last of the Japanese forces attacked without warning in one of the largest banzai charges of the Pacific campaign, penetrating the rear echelon of the American lines. After brutal hand-to-hand combat, the Japanese force was basically eliminated. Enemy dead numbered 2,351, though hundreds more were thought to have been buried during bombardments. Only 28 of the Japanese survived.