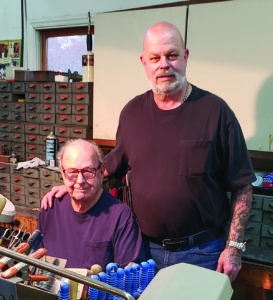

Murray Sterling has seen a lot and done a lot in his 91 years on this earth. For the past 30, he’s made a name for himself as a custom knifemaker. When approached about doing a story for BLADE® that focuses in part on his age, he agreed without hesitation.

“I’m proud that I’m still here to talk about it!” he grinned. “I love to go out to the shop and do this stuff. I don’t have any real physical ailments and I’m steady enough. I can do just about anything—and I just love doing it. It’s therapy!”

In terms of making knives, Murray seems to be at his best these days. He attributes it all to experience, saying every time he makes a knife, he refines his knowledge base. “I can make 10 knives in a row, and I’ll learn something from one to the other,” he related. “A little different, and a little easier, a little better.”

One of the most interesting things about Murray’s career is that he didn’t even start making knives until after he retired, likening it to “a good retirement hobby.” Machining was his original career choice. He recalled that back in 1947, when he was a “late teenager,” he and his cousin decided they didn’t want to go to school anymore. Murray said, “Let’s go get a job,” and they drove to a nearby tool-and-die shop. “They hired both of us,” he remembered. “My cousin didn’t stay too long but I was there for about four years.”

Flash forward about a decade and Murray had gotten married and started his own machine shop. Being in southern California in the wake of World War II, he found himself doing jobs for big companies like Hughes Aircraft and Northrop Aviation. A typical job was machining hydraulics parts for aircraft such as the DC-7 and, later, the B1 Bomber. His work product spread out across the world.

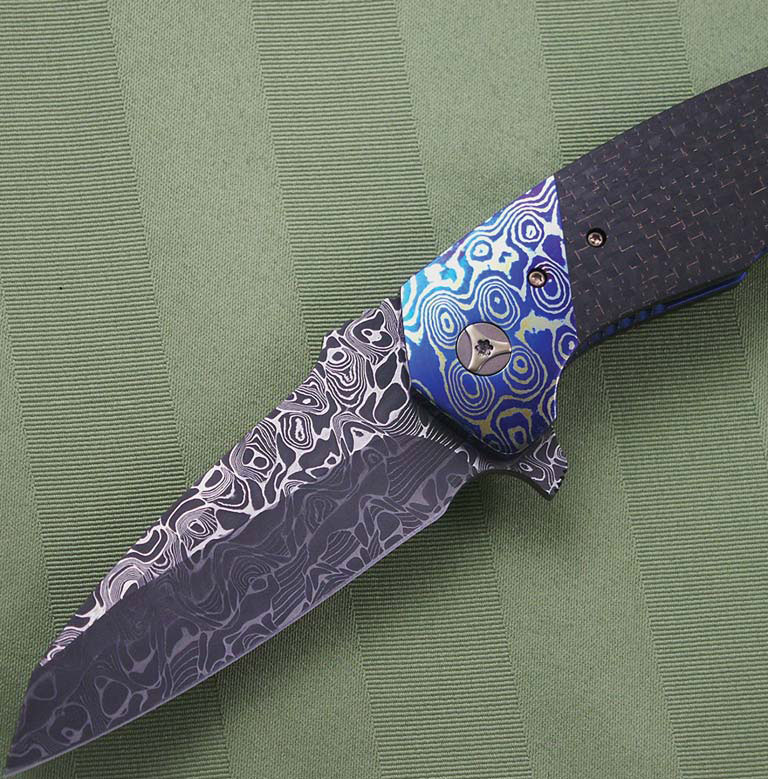

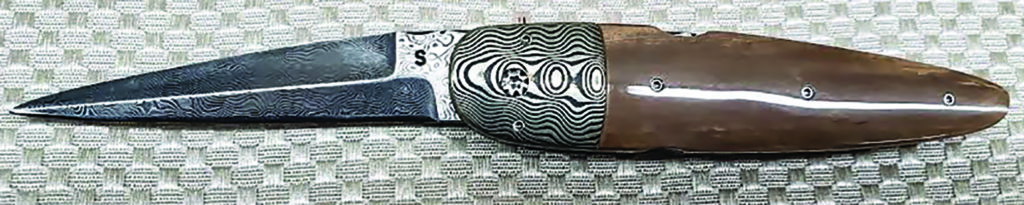

Pictured: Murray’s dual linerlock folder sports 2 3/8-inch blades of Doug Ponzio damascus, ancient walrus ivory scales and filework. Closed length: 3.5 inches.

“It was all about high quality and reliability,” he recalled of his formative days, and he carried that ethic forward over the following three decades of his successful business. In 1986, he decided to retire, but kept his shop in the family for a few more years. This was about when computer numerically controlled machines were becoming prevalent, so, Murray recalled, he figured it was time to get out of the business. Consequently, he closed up shop and brought some machines home to start making knives.

“I’m an old-school machinist. I started on old overhead belt-drive machines,” he recalled. “When I went out of business, we had some pretty modern machines, but not CNC.”

Murray doesn’t keep it a secret that he’s not a big fan of using CNCs or water-jet equipment, though he understands why makers use them and that the machines certainly make things easier. He explained that in his day all the machines had handles, but the trend continued toward “machines with buttons that can be programmed from 50 feet away.”

“When I started working in that tool-and-die shop, there were about six tool-and-die makers in there,” he remembered. “When they came in in the morning, they’d bring out their files, a cup of coffee and a cigarette. It’s hard to imagine how much hand work they did in those days. They had an old lathe and an old mill, but most of the work was done on the bench filing and sanding.”

As he reflected, he added that he admires some of the “out-of-this-world” knife designs that have resulted with the benefit of computerized, automated machines. “They do fantastic work, no question about it,” he allowed. “The machinery these days makes it much easier. If I was 20 years younger, I’d probably have one!”

FIRST KNIFE SHOW

His journey into the knife world began in 1977, when he ventured into the MGM Grand in Las Vegas for a knife and antique gun show. It was there he experienced his first custom knife show and bought his first custom knife—a coffin-handle folder from BLADE Magazine Cutlery Hall-Of-Fame® member Wayne Goddard. “That was when I got impressed with the work that these guys were doing with the equipment they had in those days,” he recalled.

Murray set out to learn knifemaking in 1989. Along the way, he had guidance and education from a lot of makers, as well as reading iconic books on how to make knives. However, he draws a distinction between that and actually learning the craft. He characterizes himself as mostly self-taught through a lot of trial and error and the determination to put in shop time.

“Hollow grinding is not something you can teach somebody,” he explained. “They can tell you how to do it and show you how to do it, but you have to put in the time and learn to get the feel for yourself. You can’t give the feel to somebody.” So, he burned up a lot of gloves, as well as his fingers sometimes, until he finally learned how to do it.

He made fixed blades until about 1991, when he talked to slip-joint master Jess Horn a lot about transitioning to making folders. Murray said that’s when he learned he needed to add a surface grinder to his shop. “I didn’t make really good folders until I got a surface grinder,” he allowed. “I learned a lot from Jess.”

That year, Murray also sold his first knife. By 1995 he had won his initial award—for best folder—at the Oregon Knife Collectors Association Show. He was on the map.

Over the course of the ensuing 25 years, he would go on to make and sell a wide variety of folders that runs the gamut of styles and mechanism applications, from traditional multi-blade slip joints to modern automatics and seemingly everything in between. His choice of blade steel is ATS-34 stainless, and a wide array of beautiful damascus forged by Mike Norris, Devin Thomas, Alabama Damascus or Doug Ponzio.

“I’ve never had a lot of luck selling wood handles, so I like a lot of stag, ivory and pearl,” he explained. He also uses acrylic to great effect. When he wanted to start doing inlay, Murray said, he turned to award-winning maker Tim Herman. “I wanted to do inlay and I called him—this must have been 15 or 20 years ago,” he recalled. “I’m still doing inlay the way he taught me, which is the hard way.”

As for mechanisms, he enjoys making several variations of locks including button, front, mid, rear and even dual locking liners. He also makes autos that feature bolster release, button release, mid-release, top release, frame release and most any release imaginable.

“They’re hot and cold,” he surmised of making autos. “Two years ago, I sold 10 right off the bat in Atlanta. Then the next year, they cooled off, so I went to something else. Every year you have to come up with something new and stay aware of the trends.”

In fact, the true problem Murray admitted to is, after making knives for 30 years or so, he must continuously come up with something new. Trends tend to go round and round, he explained, so what was hot 10 years ago will go away and then return.

Nowadays, Murray goes to only a couple of shows each year, including the BLADE Show, with his 63-year-old son, Steve, who has started making knives the past couple of years. Murray admits that the shows are getting too long for him and he gets worn out pretty quickly.

“My son goes with me all the time or otherwise I probably wouldn’t go,” he noted. “I don’t go to the ICCE Show”—he’s been a voting member of the Knifemakers’ Guild since 2000—”because it’s a two-day drive and I just don’t think I could handle it.

CHANGING TIMES

When asked about what he’s taken note of as any drastic changes in the industry over all these years, he mentioned few things in particular. One, as mentioned, is the evolution of equipment across the board. “The quality of the knives back in the day was great, but the quality of the equipment today is 100 percent better,” he pointed out. “The gravers, the machines, even the belts you can get today—2,000-to-3,000-grit belts. You couldn’t get that 25 or 35 years ago.”

The other drastic change he’s noticed is the Internet, which he believes changed the industry in terms of selling knives. While the real knife collectors still want to see and know the maker, he’s noticed a lot of impulse buyers on the Web.

Also, he added, “Instead of hundreds of custom knifemakers, today there’s probably thousands of them. They’re using water jets to cut out the blanks and using CNC machines—there’s a lot of production, it seems like. They’re still custom made,” he qualified, “but handmade is kind of going out the window.”

However, as usual throughout our conversation, Murray hesitated to grind for too long on makers who use state-of-the-art equipment, concluding, “There’s a market for everything. High-dollar, low-dollar, mid-dollar—two-dollar knives and two-thousand-dollar knives. There always seems like there’s a buyer today.”

For more information on Murray Sterling and his knives, contact him at Dept. BL10, 693 Round Peak Church Rd., Mount Airy, NC 27030 336-352-5110 fax 336-352-5105 [email protected], sterlingcustomknives.com.