Latest cleavers are a hot ticket on the camp scene

By Pat Covert

The cleaver has been sneaking up on the cutlery market for several years now. However ironic it may seem, along with the razor, it was in demand on the tactical market before it became popular for culinary attire on the camping/survival scene.

Not anymore. Cleavers are now making their case as viable tools for outdoor use.

An interesting FYI here: Why do most cleavers have a curved blade edge? The curve allows the butcher to rock the blade back and forth to make sure he or she cuts the ends of the meat cleanly.

SMALL ’n SLICEY: CRKT Folts Minimalist Cleaver Blackout

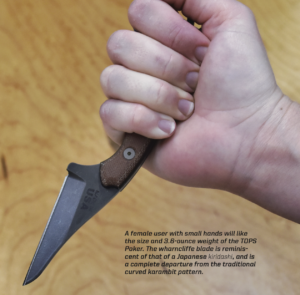

The Columbia River Knife & Tool Folts Minimalist Cleaver Blackout is the most diminutive of the test bunch. It’s billed as a neck knife and aptly so. The blade features a hollow grind for enhanced slicing, and the deeply finger-grooved—three grooves total—handle has orange G-10 scales. All black is also available.

A cleaver this light is not made for chopping—there’s simply not enough weight behind the blade. That said, the Minimalist Cleaver is not without utility. The old rope knives had deep, flat-edged blades preferred by many sailors, so I decided to try the small cleaver out on some 3/8-inch rappelling stock. The blade is wicked sharp and proved plenty long enough to slice through the rope in clean, one-stroke pulls. It even handled upper-guided pull-throughs with ease. All in all, the Minimalist Cleaver is a handy little neck knife—as long as you use it for slicing.

SPECS: CRKT FOLTS MINIMALIST CLEAVER BLACKOUT

Blade length: 2.125”

Blade steel: 5Cr15MoV stainless

Handle material: G-10

Special features: Deep finger grooves

Weight: 1.7 ozs.

Overall length: 5”

Sheath: Black thermoplastic w/neck cord

Country of origin: China

MSRP: $39.99

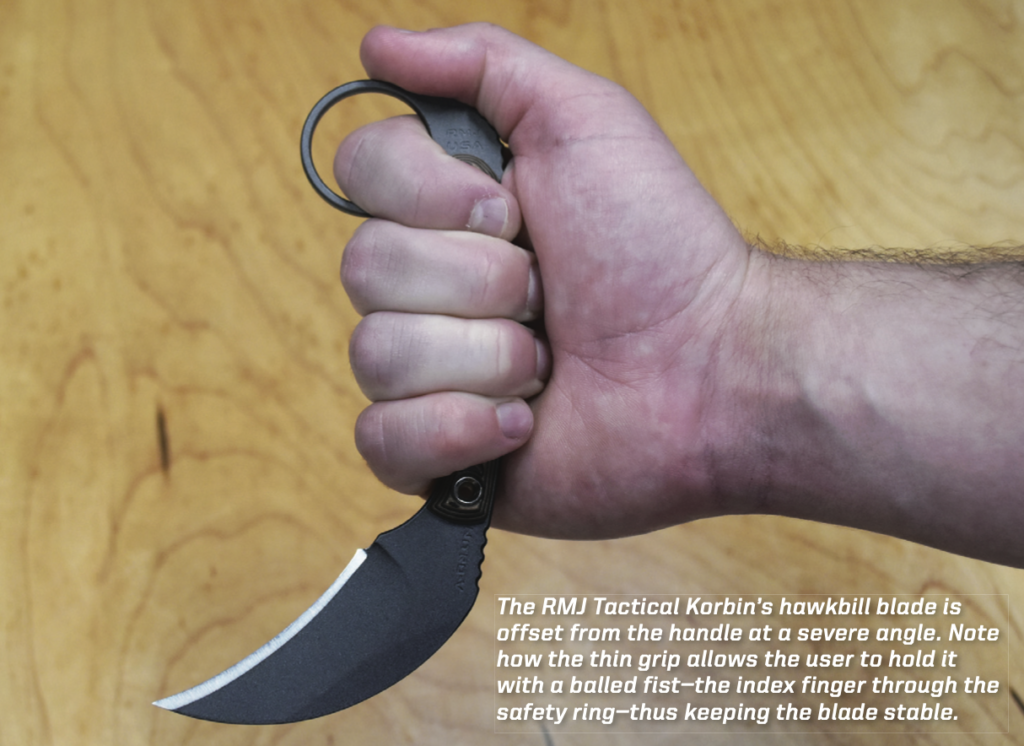

SLICK ’n WICKED: RMJ Tactical Jackdaw

The RMJ Tactical Jackdaw is a small cleaver with a blade not unlike a miniature dao, a type of Chinese sword. In true RMJ fashion, the Jackdaw’s hollow-ground blade has upscale steel with a tungsten Cerakote® finish. The handle includes a nice index finger groove. The scales are machined blaze olive G-10 over orange liners, with diagonal grooves for enhanced purchase. The sheath can be worn for horizontal outside carry or reconfigured vertically inside the waistband.

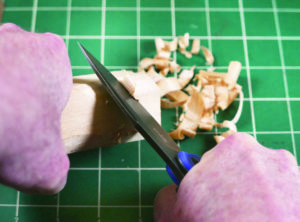

The Jackdaw is another small cleaver that lends itself to slicing more than chopping. The blade rivals that found on many tactical knives but since the focus here is on camping, I needed to keeping it in its lane. I gave it a go slicing some Louisiana-made 1.25-inch Boudin sausage—Asian meets Cajun, if you will. It made quick work of taking off nice, clean slices. There’s no doubt the Jackdaw would excel in other chores such as cutting rope and paracord, skinning bark, cutting notches in wood and the like. While its looks may not scream camp knife, it’s more than willing to prove you wrong.

SPECS: RMJ JACKDAW

Blade length: 3.25”

Blade steel: Nitro-V stainless

Handle material: G-10

Special features: Chinese dao-style blade

Weight: 2.9 ozs.

Overall length: 6.625”

Sheath: Molded black Kydex, Scout carry

Country of origin: USA

MSRP: $200

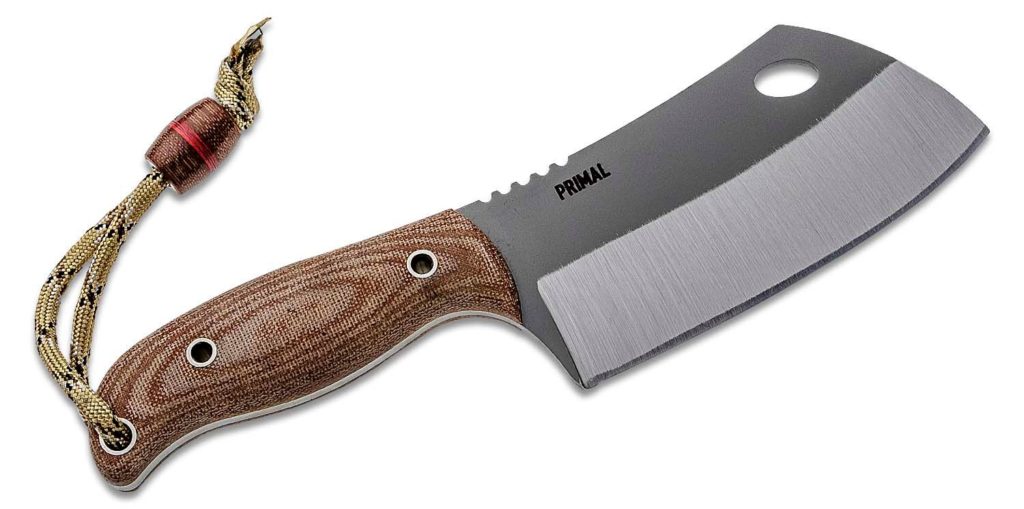

PRIMORDIAL CHOP: Condor Tool & Knife Primal Cleaver

Of the test bunch, the mid-sized Condor Tool & Knife Primal Cleaver most resembles the shape of the archetypical cleaver. It has a decent amount of heft, the bead-blasted, flat-ground blade does the heavy lifting and there’s an ovate hole in the blade for hanging. The curvaceous handle sports layered scales and there’s a tube lanyard hole in the base replete with a paracord lanyard ready for duty.

I first tested the Primal Cleaver on a variety of veggies. The blade easily chopped through tomatoes and bell peppers in clean, single whacks. Then I tried it at dicing both and the blade performed like a champ. I also tried it on 2-inch-thick beef tenderloin and it chopped out slices admirably. The handle is very comfortable and, though it didn’t fill my medium-size palm, what you give up in length you gain in lighter weight and portability over a full-sized cleaver. I rate this as a very competent bulldog with enough heft to perform a myriad of cooking chores.

SPECS: CONDOR TOOL & KNIFE PRIMAL CLEAVER

Blade length: 4.09”

Blade material: 1095 carbon steel

Handle material: Orange Micarta®

Weight: 5.75 ozs.

Overall length: 7.89”

Sheath: Brown leather belt model

Country of origin: El Salvador

MSRP: $84.98

DUAL PURSUIT: White River Knife & Tool Camp Cleaver

The White River Knife & Tool Camp Cleaver somewhat resembles a shortened Malaysian parang, which is ideally suited for chopping. This is the beast among the test group. The stonewashed blade sports a durable flat grind. A hole in the blade allows for hanging around the campfire for ready access. The handle is nicely sculpted with an ample palm swell and there’s a lanyard hole in the base. White River provides a well-crafted square-based belt sheath.

Anything but typical, the full-size Camp Cleaver’s blade design struck me as one useful for both chopping and slicing, so I gave it a go both ways. I tested the blade on a couple of 2-inch-thick beef tenderloins for a stew. I know, extravagant, I love a good stew. The Camp Cleaver’s heft and sharp edge took off slices of the tenderloin effortlessly, and performed equally as well cubing the meat into squared chunks. Potatoes fared likewise. If you don’t mind packing a full-size cleaver, the White River offering will return the favor by prepping meals for a horde of campers.

The White River Camp Cleaver is 10.125 inches of chopping and slicing heaven. At 8.2 ounces it’s a cleaver with plenty of heft for group food prep, and its CPM S35VN stainless steel blade provides superb cutting ability.

SPECS: WHITE RIVER KNIFE & TOOL CAMP CLEAVER

Blade length: 5.625”

Blade steel: CPM S35VN stainless

Handle material: Black Micarta®

Special features: Traditional hole in the blade for hanging

Weight: 8.2 ozs.

Overall length: 10.125”

Sheath: Brown leather belt model

Country of origin: USA

MSRP: $250

CLEAVER CORNUCOPIA

As you have no doubt deduced, cleavers come in all shapes and sizes. The CRKT Minimalist necker is a nifty companion for a variety of small chores. The RMJ Jackdaw will slice with the best of them, and its versatile sheath is a nice bonus. Condor’s Primal Cleaver is a great blend of chop-ability and portability. The beastly White River Camp Cleaver is a full-size workhorse at preparing food for a cadre of campers. Next time you’re getting your gear together for an outing, consider the cleaver as part of the package!