Prepare massive meat feast with one of these barbecue beasties at hand.

The barbecue/brisket knife is an indispensable tool for those who prepare brisket and other large-scale meat dishes. Makers go the extra mile to provide the toughness and tensile strength needed, along with a tip that stays sturdy to separate meat and prepare it for serving. Individual recipes include the good looks and visual appeal that make owning and using the best in such knives a pleasure.

Ben Anderson: Brisket Slicers For The Barbie

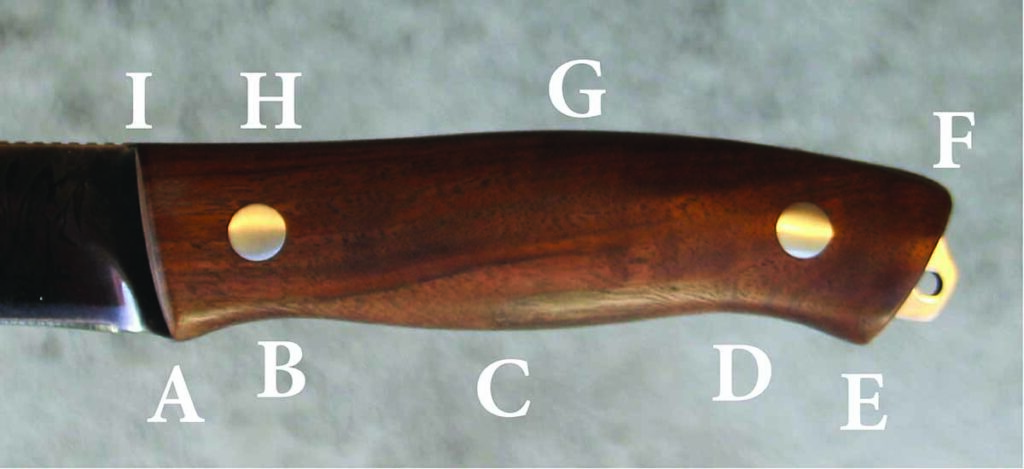

Ben Anderson of Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia, features his artisan’s perspective in two beauties that allow form and function to seamlessly blend. He calls both brisket slicers, and in each case he has styled the big carbon steel blade for use with large pieces of meat. One features a blade of 52100 high carbon steel, handle of ironwood and ebony with textured and filed brass spacer, overall length of 27.5 inches, blade of 19.7 inches, and leather sheath. The second is a stunning piece with a 12.6-inch blade of mosaic damascus in 1084 carbon and 15N20 nickel-alloy steels, and a handle of ringed gidgee with a damascus spacer. Overall length: 19.7 inches.

“The blade shape just seems to be a favorite of the brisket guys [in Australia],” Ben commented. “I think people like it because it’s just an aggressive-looking shape that’s a bit reminiscent of a katana. Most of my time as a maker I’ve offered full customization for my clients, so this really pushed me to try all different shapes, sizes and color combinations.”

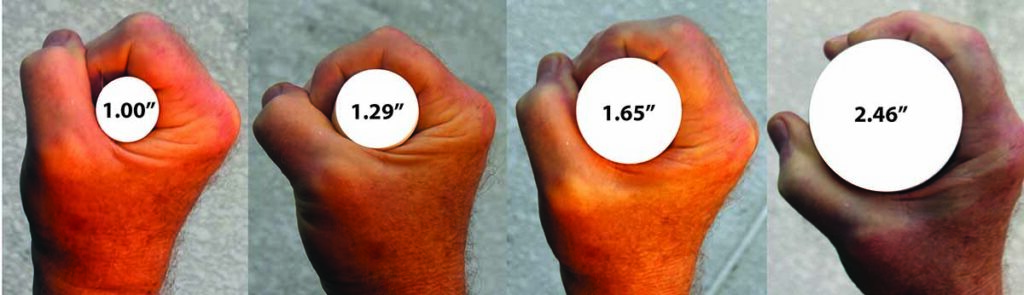

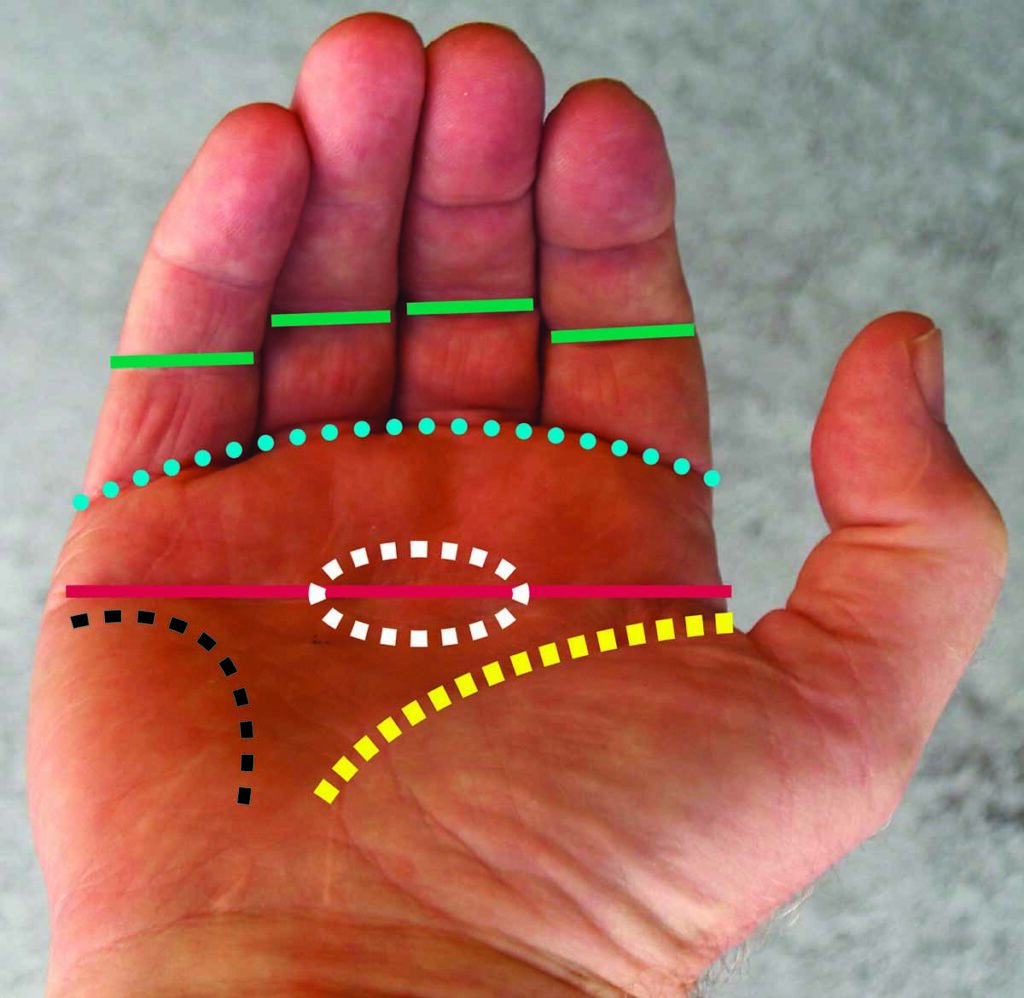

A custom knifemaker for about six years now, Anderson uses precision specifications in crafting his brisket knives to perform. “On my standard kitchen knives I’ve always aimed for a ricasso height of around 18 millimeters [.7 inch], which made my handles around 20 millimeters [.79 inch] tall at the front and tapered out to around 5 millimeters [.196 inch] bigger at the back. On the bigger brisket knives I aimed for a ricasso height of around 23 millimeters [.9 inch], which made the handles around 25 millimeters [.98 inch] tall at the front and again tapered to around 5 to 7 millimeters [.196 to .275 inch] bigger at the back. I like to scale the handles up with the blades,” he noted, “so it all looks in proportion. It also helps with the balance a bit.”

Anderson’s brisket knives have found their way into competitions with a customer who uses them to prep and slice. Ben’s maintenance and upkeep includes Renaissance Wax for long-term storage after a good cleaning. For everyday servicing a bees wax or mineral oil wipe down for the handle works best.

Of course, since Ben is Australian, his take on the barbecue event itself is enlightening. “A barbecue here is often as simple as a 24-pack of sausages and a loaf or two of bread and some basically burnt-to-a-crisp onion,” he laughed. “As for myself, I’m usually pretty happy with a simple steak and sausages.”

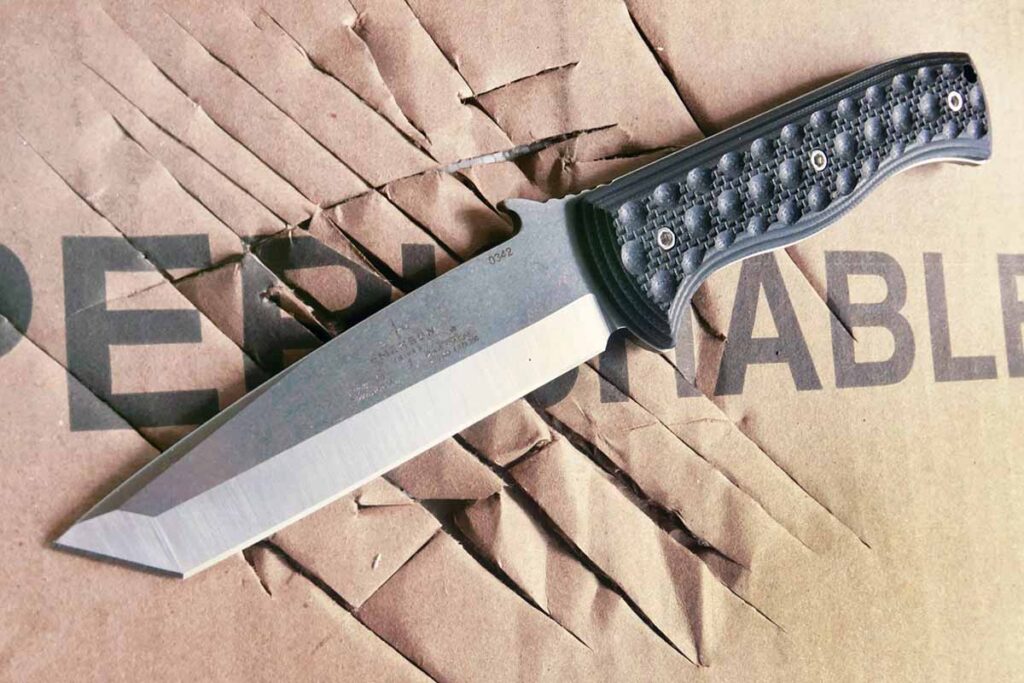

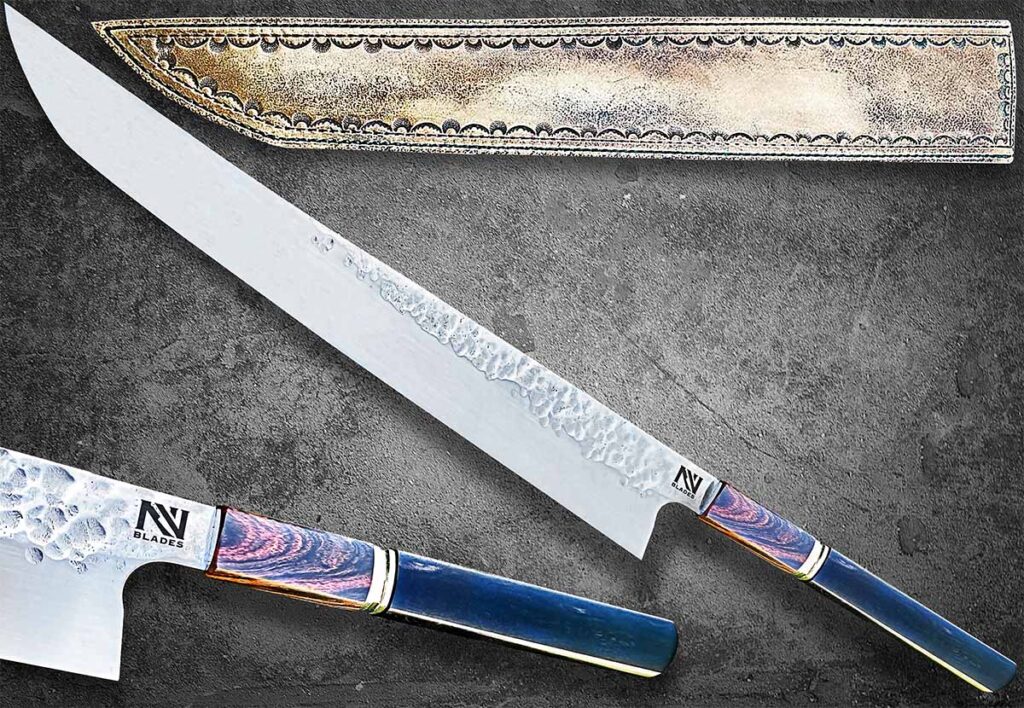

Peter Pruyn: San-Mai Slicer

Peter Pruyn of Grant’s Pass, Oregon, recently produced a brisket slicer that is pleasing to work with and also admire next to the cutting board. His 13-inch blade in a stainless/high-carbon san-mai construction of respective 416 and 52100 steels is complemented by a handle of his favorite handle material from Voodoo Resins, and a copper spacer. Overall length: 18 inches. A zippered, padded pouch is included.

The pouch, Pete says, is more practical in a kitchen setting and protects the knife. If the knife is included in a set, his preference for protection is a leather knife roll.

“This particular knife is designed for slicing large pieces of beef,” Pruyn related. “I made it for a customer who uses it for commercial-size briskets. When I needed to design a knife for that purpose, I called a friend, Rob Baptie, who barbecues and cooks briskets and other meats professionally. He described a very long, thin blade with a little distal taper and vertical scallops the entire length of the blade. Often referred to as a Granton-style blade, it has a handle that supports slicing with a pulling motion.”

Peter forged the blade to about 1/8-inch thick. “The 52100 has always been an excellent steel for butcher and chef’s knives due to its abrasion resistance, and it takes an excellent edge and retains it very well. The stainless protects the core steel and makes it easier to maintain,” he observed. “I also etched the blade, which makes the 52100 more rust resistant, like a forced patina.”

The Voodoo Resins handle material is easy to work with and extremely durable. “It doesn’t change with time, temperature or humidity,” Peter said. “Its creator, Matt Peterson, made a custom color for this knife, which was part of a 14-piece set. For the bolsters I chose copper more for its aesthetic appeal with the other materials than anything else. When you make a custom knife for something like this you have to think about how it looks and not just a comfortable handle and a practical, durable design. It’s part of the whole package.”

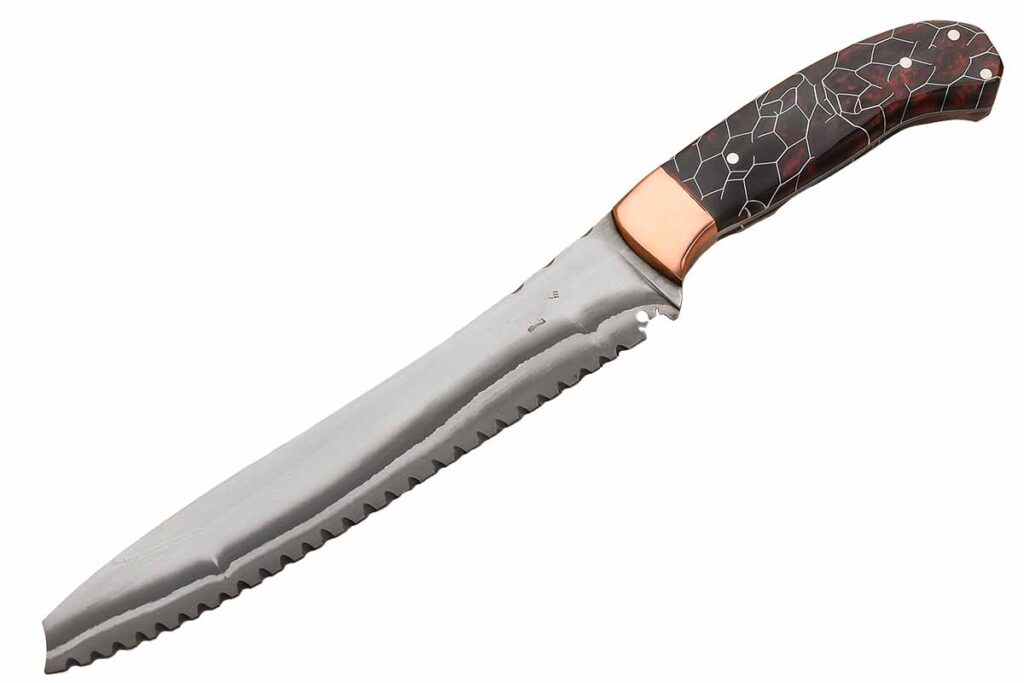

Matt Williams: Barbecue Balance

A heavy chef’s knife with a santoku influence was the goal for Matt Williams of Bastrop, Texas, with his beauty of 400-layer random-pattern damascus in 1084 carbon and 15N20 nickel-alloy steels. The blade is 9 inches long and the handle is spalted pecan, cedar elm and a white oak dowel in a combination that evokes the maker’s woodworking skills. His knives are influenced by feedback from customers who have told him what they really want in a solid performing knife. His price for his BBQ Chef’s Knife starts at $750.

“The blade’s distal taper is .169 to .05 inch,” Matt noted, “and this distal allows for some more delicate work to be done at the end of the blade. Sometimes you need to slice up some peppers or dice up something tasty. The handle is long to balance the heavy blade out. It’s thin because I like wa [octagonal] handles, and this is my interpretation done on a wood lathe. I turn the whole handle and the dowel. I harvest, mill and stabilize most of my wood. They are all local hardwoods. I know these woods well and their capacities.”

When designing his BBQ Chef’s Knife, Matt relies more heavily on balance than weight. His perspective counts on a solid feel in a pinch grip. “Prepping 200 fruit and veggie trays in eight hours will test your wrist,” he smiled. “I learned not to fight a forward-leaning blade. I worked in food prep when I was younger and I have always been drawn to this shape for its overall utility.

“I want the knife to slice well through meat and to be able to break a joint,” he concluded. “Afterwards, it will also look pretty next to a pile of barbecue!”

Editor’s note: Due to fluid market conditions, all prices listed are subject to change. Please check with the applicable maker for the latest in pricing.

Read More- Best Japanese Kitchen Knives Worth A Look

- BLADE 101: Types Of Kitchen Knives

- 5 Best Meat Cleaver Options

- 5 Best Santoku Knife Options

- 5 Best Serbian Chef’s Knives

- The Beauty Of Handmade Kitchen Knives

- Best Kitchen Knife Set To Upgrade Your Galley